He was a long way from home.

Far from the fjords of Norway,

across the Atlantic ocean and beyond,

his violin had brought him

into the continent of America

to pose for this photograph.

His name was Ole Bull,

the greatest Norwegian violinist of the 19th century.

Far from the fjords of Norway,

across the Atlantic ocean and beyond,

his violin had brought him

into the continent of America

to pose for this photograph.

His name was Ole Bull,

the greatest Norwegian violinist of the 19th century.

|

| Royal Mail Steamship Russia of the Cunard Line The Illustrated London News 9 September 1867 |

It was the start of Ole Bull's new concert tour of America, returning after an absence of ten years. He arrived in New York City on December 11, 1867 aboard the steamship S.S. Russia. This hybrid sail and steam ship was the newest addition to the Cunard line, the first with a steam powered screw propeller. It was 358 ft long and 43 ft wide, capable of reaching 14 knots. The three masts of sails offered assurance that in the event of engine failure the ship could still reach port. That summer it had just started service as a Royal Mail ship operating on a regular route from Liverpool to New York. It was a fast ship. A voyage usually took only 10 days including one stop in Queenstown, Ireland. The Cunard line designed it for first-class passengers, initially limited to 235 berths, and the ship was very well appointed. The typical fare was $150, payable in gold.

|

| S.S. Russia, Cunard Line, c. 1867-70 Source: Hoboken Historical Museum |

Ole Bull was then age 57 and very accustomed to traveling. It must have amused him to be sailing onboard the S.S. Russia having just played in Moscow and St. Petersburg earlier that year. After 30+ years on the stage, his virtuosity on the violin had taken him to Rome, Paris, Berlin, London, and countless concert halls big and small throughout Europe. Now he was returning to the new world of America, a place he knew well from previous tours.

When he was 18 he left home in Bergen, Norway to pursue his dream of a musical life. After a short period in Oslo, and then Copenhagen, he moved on to Paris where he first heard the great Italian violin virtuoso, Niccolò Paganini (1782 – 1840). This encounter with Paganini inspired Ole Bull towards a higher ambition to become a solo violin artist. Through hard work and a natural talent, he soon made a mark in Italy and then London. By age 25 he was celebrated as Norway's best known virtuoso.

Ole Bull's first concerts tours around Europe were at a time of relative peace following the turbulent age of Napoleon. Musicians, writers, and artists were enjoying a new freedom to travel between nations. It was one of the important factors that drove the Romantic movement in all the arts. Ole Bull's contemporaries: Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847), Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849), Robert Schumann (1810–1856), Franz Liszt (1811–1886) were all making their mark as concert pianists and composers.

It was also a revolutionary time for politics and civil rights as well. Since 1387 the three nations of Scandinavia: Denmark, Sweden, and Norway had struggled with a complicated relationship of different monarchs and unions. In earlier centuries, Norway and Denmark were joined together, but in the 19th century following the Napoleonic era, Norway and Sweden became two states united under one monarch, yet with separate governments and laws. Real independence for Norway would not happen until 1905 when the union with Sweden was finally dissolved. For Ole Bull this complicated "personal union" between the two countries

aroused a lifelong patriotic passion for Norwegian culture and a devotion

to ideals of freedom.

|

| Statue of Ole Bull in Bergen, Norway Source: Wikipedia |

After his first success in the great cities of Europe, Ole Bull chose a daring westward direction that his contemporaries must have thought foolhardy if not mad. In November 1843, he embarked on a visit to the United States not returning to Europe until 1845. Seven years later in 1852 he came back and stayed even longer. He was so impressed with the country that he even applied for U.S. citizenship. (But never completed it.)

It was early in that visit that he came up with a grandiose idea to develop land in western Pennsylvania for Norwegian immigrants. For $10,000 he bought 125,000 acres where he established four settlements: New Bergen (now known as Carter Camp), Oleona, New Norway, and Valhalla. It was an ambitious project, yet soon hundreds of Norwegian families came to join his colony. The settlers' first year was very difficult, in part because they were unfamiliar with building farms on this kind of rugged terrain with its thick hardwood forests. Ole Bull had also been swindled by the land agent who never held legal title to the better parts of the land. Sadly the venture failed as the Norwegian immigrants abandoned the Pennsylvania communities for more favorable regions in the Midwest. It took years for Ole Bull to resolve the lawsuits, repay his debts, and regain his reputation. Partly out of frustration with his legal problems he went back to Norway in 1857. Today all that is left of his dream is 132-acres in Ole Bull State Park in Potter County, Pennsylvania.

|

| Springfield IL Daily State Journal 27 December 1867 |

When the S. S. Russia tied up at the New York dock in December 1867, Ole Bull was arriving to a new re-United

States, devastated by 4 years of terrible civil war. Parts of the nation

were now rebounding with enthusiasm for a modern industrial future, but other parts

were still wrestling with the monumental problems of race, division,

and injustice. Only two years before, the country had recoiled in horror at the assassination of

President Lincoln. Now the accidental President, Andrew Johnson,

was leading a damaged nation on a different regressive path. In the next year he would be humiliated by a bill of impeachment from Congress.

In 1865 the passage of the 13th amendment abolishing slavery transformed America's repressive social structure. But changes to its constitutional foundation dealing with citizenship rights and equal protection under the law would not happen until the passage of the 14th amendment in 1868. A democratic idealist from Norway would have noticed these changes.

For some reason Ole Bull was determined to start his concerts in Chicago. He had first played there in 1853, and then again every season until 1857. Over this last decade the Windy City had nearly tripled its population and now boasted of 300,000 citizens. It was in competition to become the hub for America's westward expansion. It was America's new center for commerce, industry, and innovation. It was also a center for music and theater.

In 1867, on a cold December day just after Christmas, Ole Bull would hardly have recognized the city when he checked into the Tremont House, the finest hotel in Chicago. He was with his business manager, Mr. F. Widdows, and his son, Alexander Bull, then 28 years old.

_ _ _

|

| Tremont House Chicago Illustrated, January 1866 Source: Chicagology.com |

The Tremont House was one of the first inns for travelers in Chicago, built when the city's streets were first laid out. It's possible Ole Bull may have stayed there before in the 1850s, but in 1867 he must have been astonished to see what they had done to the place.

In Chicago's first decades, city blocks and streets were constructed without regard to the underlying geology or the close proximity of Lake Michigan. By the 1860s the infrastructure problems of drainage, sewage, and water needed a major fix. For Chicago's grand masonry buildings this was accomplished by literally lifting the entire structure with thousands of jack screws up to the new street grade. In 1861, the Tremont House, six stories tall with a footprint taking up over 1 acre, was raised 6 feet higher by 500 workmen who slowly and simultaneously turned 5,000 jackscrews. The hotel's business continued right through the construction and not a single pane of glass was broken. (Wooden buildings, however, were merely moved by being placed on rollers and drug/pushed to a new location in another district. )

|

| The Briggs House being raised, 1866 Source: Chicagology.com |

* * *

|

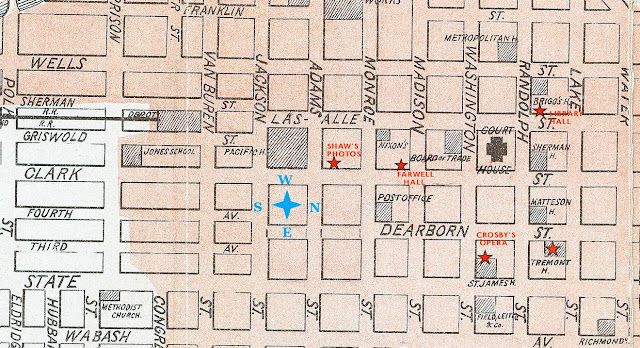

| Excerpt from 1871 Map of Chicago |

The Tremont House was located on the corner of Lake and Dearborn Streets, two blocks from the courthouse and close to all the big theatres. As a seasoned entertainer, Ole Bull had already discovered the value of photographs for publicity. But in 1867, particularly in America, the new technique of carte de visite albumen prints, which could be reproduced in any number, had become the latest media fashion. There were dozens of photographers very close to his hotel. Shortly after his arrival in December he chose to have his picture taken at the studio of William Shaw on South Clark St., a short walk from the Tremont.

On the back of Ole Bull's carte de visite photo

is the imprint of the photographer.

Shaw's Mammoth

Photograph Rooms,

186 South Clark St.,

Chicago, Ill.

____

Pictures taken in Cloudy Weather

at these Photograph Rooms

SUPERIOR

to those taken elsewhere in town on a

fair day.

is the imprint of the photographer.

Shaw's Mammoth

Photograph Rooms,

186 South Clark St.,

Chicago, Ill.

____

Pictures taken in Cloudy Weather

at these Photograph Rooms

SUPERIOR

to those taken elsewhere in town on a

fair day.

William Shaw was about 33 years old in 1867 and had been at this location since about 1865. In April of that year he advertised "One Hundred Thousand Photographs of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. Cards, $12.00 a hundred; Medallions, $6.00 a hundred."

|

| Chicago Tribune 24 April 1865 |

|

| Chicago Tribune 5 May 1865 |

Ole's son Alexander, an accomplished violinist, had visited the US once before in 1856. I suspect this concert tour was also a special trip for father and son, as Ole's wife, Alexandrine Félicie Villeminot, had tragically died in 1862 at age 43. Of their six children only Alexander and his two sisters, Eleonore and Lucie, were still living in 1867. As this concert tour progressed, Alexander's name appeared on advertisements as Ole's business manager. It seems likely that he came on this trip to gain experience in the American practice of show business.

|

| Chicago Republican 30 December 1867 |

The theater hired for Ole Bull's first concerts in Chicago was the new Farwell Hall at the Young Mens' Christian Association Building. It had just opened in September 1867 and measured 121 feet by 81 feet. with a ceiling 45 feet from the floor. With two galleries surrounding lower floor, it could seat 3,500 people. The hall's arrangement allowed good views of the platform stage and excellent acoustics. It was lit from large windows and double reflectors. On 30 December 1867 Mr. Widdows placed advance notices in the Chicago papers to announce Ole Bull's concerts.

|

| Young Men’s Christian Association Building (Farwell Hall) Source: Chicagology.com |

On the Sunday morning before his first concert on January 6th, the Norwegian Society of Chicago paid a call on Ole Bull at the Tremont House. He was given a cordial welcome, and a serenade from a "quintette" of Norwegian singers, accompanied by the Great Western Band which played several national pieces, some of them composed by Ole Bull himself. In thanking his fellow countrymen for the reception, it was reported that Ole spoke in Norwegian. He "hoped that they retained the same inspiration for liberty, freedom and equality that they had always had in the old country, and that they would always be good citizens of (this) great country. He again thanked them, and concluded by proposing nine cheers for the government, which were heartily given. He also spoke afterwards in the warmest terms of Chicago, which was to be the future metropolitan city of the world—which was to make the next President, and thus to control the destinies of America, which was in its turn to control the world."

|

| Chicago Republican 3 January 1868 |

Ole

Bull's music programs followed a formula that he had used in his

previous tours. It was a kind of refined variety show which offered more

than just his violin playing, though he was still the headliner. He

usually traveled with a vocalist or two, and a pianist, who would

accompany the singers and Ole, and sometimes perform solo too. On this

tour he had two opera vocalists, Signor Ignatz Pollak, a baritone, and

Madame Varian, a "prima donna" soprano. Madame's full name

was Charlotte Varian Hoffman and she was the wife of the pianist on

this program, Edward Hoffman. I believe these artists were American, as their honorifics were a convention of opera's Italian origins.

There was a usually an orchestra, as big cities like Chicago employed hundreds of talented musicians in bands and theater orchestras. For this first concert notice the orchestra would open with an overture to Hamlet by E. Bach, an unknown composer who, as far as I can determine, was no relation to old Johann Sebastian Bach. Signor Pollak would follow with an aria from a Donizetti opera. Then Ole Bull would play one of his own compositions, Cantabile Doloroso e Rondo Giocoso. Madame Varian was next in a song from Charles Gounod's new opera, Romeo e Guiletta, which had recently premiered at Crosby's Opera House in Chicago. Mr. Hoffman then came out to play two Fantasias on the piano, pieces that were a kind of variations on a another composer's theme. Then Ole returned to close the first half with his Nightingale Fantasia upon a Russian Legend.

The second half started with another orchestral favorite, selections from Gounod's Faust. Madame Varian then performed Auber's "French Laughing Song", and Sig. Pollak sang a Baracola by Campana. Ole Bull was officially listed to play only one number on the second half, a Polacco Guerriera, but he likely had other solo encores. Especially popular were his fiery variations on Yankee Doodle or Arkansas Traveler. Varian and Pollack would then return for a duet, L'Estai by Mabellini. The evening finished with a finale, Grand March of the Priests from the 1843 oratorio Athalia by Mendelssohn. Admission was $1.00, reserved seats, fifty cents extra.

|

| "I Love Thee Still", as sung by Mme. Charlotte Varian Hoffman, 1866 Source: Historic American Sheet Music, Duke University |

The weather was abominable. Just above the concert's review in the Chicago Republican on 7 January 1868, was a short report. "The weather of yesterday, if judiciously distributed, would knock the sunshine out of an entire season in many localities, or give the blues to an extensive community. Rain, hail, snow—just enough to be miserable—mud in any quantity, frost, and the most leaden-colored of skies, all contributed to the general wretchedness of our people."

Despite this, Ole Bull played to a packed house at Farwell Hall on Monday evening. The reviewer in the Chicago Republican wrote:

"Comets of astounding brilliance are but rare visitors, and their visits should be marked with abundant admiration. The genius of the violinist who made his appearance last night in Chicago is one of these rare visitors to earth, and the popular enthusiasm over it is therefore abundantly excusable." [When Ole Bull came on stage,] "the noisy applause [relapsed] to a quiet as still as the night when the first tones of his noble instrument floated through the house. In rapt attention the same stillness was held throughout his whole performance, until the last flourish was swallowed up in deafening applause. A profusion of bows availed nothing to subdue the audience, only the ravishing tones of that violin held the ample power.

Such was the picture at each of the three appearances of the great violinist in the concert. To one who heard him for the first time, the impressions left are of a tall, straight, impressive-looking man, with an intelligent head, whose gray locks indicated the ripened talent, and in whose artistic effort there was nothing short of perfection in execution, and strong impassioned feeling. Every possible resource of the instrument is exhausted in the playing, and it seems no violin had ever held so much music as does this one. In his hands it comes very near to a thing of life. In all these words of praise to the player, it should be said deservedly that the violin which was used last night is one of the most superb instruments in the world. Some of its tones are almost amazing in their purity and strength.

The following morning,

as newsboys were hawking

the Tuesday edition of the papers,

a fearful noise rang out.

It happened while

Ole and company were

having their breakfast.

It was an alarm sound familiar

to the people of Chicago,

but maybe not to visitors from Norway.

as newsboys were hawking

the Tuesday edition of the papers,

a fearful noise rang out.

It happened while

Ole and company were

having their breakfast.

It was an alarm sound familiar

to the people of Chicago,

but maybe not to visitors from Norway.

FIRE! FIRE!

|

| Chicago Tribune 8 January 1868 |

It was an all too common catastrophe

in the great cities of America.

Theaters were particularly at great risk to fire

with gas and oil lamps near stage sets

made of wood, paint, and canvas.

in the great cities of America.

Theaters were particularly at great risk to fire

with gas and oil lamps near stage sets

made of wood, paint, and canvas.

|

| Chicago Republican 8 January 1868 |

The fire was first noticed at the Y.M.C.A. building at 9:00 AM, Tuesday morning. By the time firemen reached the scene, the blaze had reached the roof. It collapsed into Farwell Hall at about 9:30. Within hours the fire had destroyed the entire structure. The report on Wednesday noted that "the Great Western Band lost a number of their instruments which they left in the hall over night expecting to use them again in assisting at Ole Bull's concert. Their loss amounts to about $600.

"A Steinway grand piano used on the occasion, and belonging to Smith & Nixon, was destroyed. None of Ole Bull's effects, or of his troupe were lost. The piano in question was an elegant new scale grand; just perfected by Steinway & Sons, and was the first instrument of the kind ever sent to Chicago. It was valued at $1,500.

"As yet, the full amount of the loss cannot be correctly estimated, but it is computed in round numbers at $600,000."

There would be no second concert that evening for Ole Bull.

|

It was the 7th day of January, 1868.

The year had only just started

and yet more adventures awaited Ole Bull.

The year had only just started

and yet more adventures awaited Ole Bull.

There were more photographs too.

Part Two

of Ole Bull, Adventures in America

will follow next week.

of Ole Bull, Adventures in America

will follow next week.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where violins is never the answer.

Please note that

this Sepia Saturday theme image

is of Alexander Bull

playing the violin

of his father, Ole Bull.

this Sepia Saturday theme image

is of Alexander Bull

playing the violin

of his father, Ole Bull.

6 comments:

A cliff hanger! So much to absorb from this. I was amazed at the lifting of the buildings. What a feat. And the thought of a fire crossed my mind before I got to that part of the story. The reviewer certainly had high praise for Ole. Thank you for this well-told story! I look forward to the next installment.

Very interesting. For a man who played such refined music I wonder how his first name was pronounced, it almost seems like a nickname rather than a formal name but perhaps it loses something in translation.

I wonder how Bull's violin was spared. Did he take it with him to breakfast?

Like Kathy, I'm amazed at the lifting of the buildings. If they knew how to do it, why didn't they know how to prevent it?

Fantastic — another series! This first installment is fascinating, from Ole’s career to his attempt to establish a Norwegian community in Pennsylvania to the tragic fire after his return concert in Chicago. I can’t wait to read the second installment. Also, a question for you: How did you find which ship he arrived on in 1867? I have an ancestor who arrived in 1865 and would like to find her ship.

Thanks, once again, for a well written engaging tale, with photos to support it entirely. I wonder what will be coming along next in this series!

Well I'm hooked! Waiting for next week's Part II. :) Between the photos of Alexander and his dad and their respective poses, Ole definitely has the edge on panache!

Post a Comment