It's a very curious postcard photo.

A well dressed gentleman is seated in a parlor room

holding a vintage telephone receiver to his ear.

Next to him is a small bird cage

which has a set of headphones

stretched over the bars of the cage.

There is no explanation,

only a caption that reads:

Mr. Geo. R. Sims and his pet canary.

A well dressed gentleman is seated in a parlor room

holding a vintage telephone receiver to his ear.

Next to him is a small bird cage

which has a set of headphones

stretched over the bars of the cage.

There is no explanation,

only a caption that reads:

Mr. Geo. R. Sims and his pet canary.

Is the man actually placing a call to the bird?

What kind of conversation can one have with a canary?

Is the bird even listening?

Maybe it's a scientific experiment.

I can find no references to this image on the internet.

All I can say is what the caption tells us:

Mr. George R. Sims and his pet canary, name unknown.

But Mr. Sims turns out to be, in his time,

a renowned English journalist, poet, dramatist, and novelist.

His full name was George Robert Sims (1847 – 1922).

|

| George Robert Sims (1847 – 1922) circa 1910 Source: Wikipedia |

After the publication of his first works in 1874, Sims quickly established himself as a prolific author in many forms from plays to poetry. He was best known in Victorian times for his weekly column of light-hearted humorous sketches called "Mustard and Cress", published in The Referee, a British Sunday newspaper. Beginning in 1877 Sims wrote a story every week for 45 years until his death in 1922. His subject matter was "sprinkled with neat little epigrams in verse, patriotic songs or parodies, with jokes, puns, conundrums, catch-words. He talked of politics... philanthropy, amusement, reminiscence, food and drink, and such travel as so confirmed a Cockney could enjoy. ...he would champion the cause of the unfortunate middle classes.... He took his readers into his confidence, and told them all about... his friends... his pets.... And he contrived to do this without ever becoming egotistical or a bore."

This quote from his obituary in The Times, 6 September 1922, gives a succinct description of George R. Sims.

"so attractive and original was the personality revealed in his abundant output—for he was a wonderfully hard worker—that no other journalist has ever occupied quite the same place in the affections not only of the great public but also of people of more discriminating taste.... Sims was indeed a born journalist, with the essential flair added to shrewd common sense, imagination, wide sympathies, a vivid interest in every side of life, and the most ardent patriotism.... He was [also] a highly successful playwright... a zealous social reformer, an expert criminologist, a connoisseur in good eating and drinking, in racing, in dogs, in boxing, and in all sorts of curious and out-of-the-way people and things."

Clearly George R. Sims was a familiar enough writer in his time to be easily recognized from a photo. Which may explain why this postcard of him with his pet canary was chosen for a Christmas greeting in 1904.

With Best wishes for a Happy

Xmas & Prosperous 1905 hoping all

are well, we are alright, love to all from

Arthur & Lottie

Not quite forgotten.

Xmas & Prosperous 1905 hoping all

are well, we are alright, love to all from

Arthur & Lottie

Not quite forgotten.

It was sent in December 1904

to Mrs. G. Johnson

of 64 Northcote Road

St Margarets

Twickenham

in London.

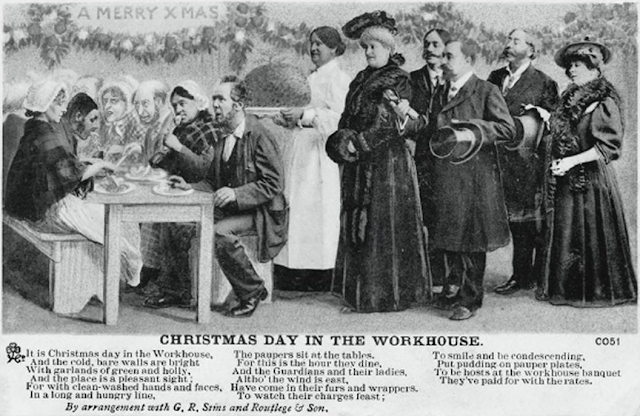

In addition to his regular column for The Referee, George Sims wrote several novels, thirty plays, and numerous collections of short stories, essays, and poetry. However, despite Arthur's quip on this postcard, most of Sims's output is now forgotten. But one ballad, Christmas Day in the Workhouse, stands out as it became popular enough to be imitated by other writers for many decades. It was first published in 1877, just when Sims was starting to write his column for The Referee. It is in the form of a dramatic monologue where a poor man criticizes the harsh conditions found in the English and Welsh workhouses of the period.

|

| "Christmas Day in the Workhouse" a postcard c1905 Source: Wikipedia |

These workhouses were the result of the 1834 Poor Law. This act passed by the British Parliament placed a severe limit to the social assistance given to the poor. Food and shelter could only be dispensed at the workhouse. Paupers were separated into different classes and by sex. The institutions were purposely designed to be so disagreeable that only people who were truly destitute and indigent would demean themselves to apply for relief. By the 1870s, the state of poverty was so shameful that Sims, a young journalist campaigning for social reform, felt compelled to respond in a public way by writing a ballad about how severe hardship affects the human spirit.

It is Christmas Day in the Workhouse,And the cold bare walls are brightWith garlands of green and holly,And the place is a pleasant sight;For with clean-washed hands and faces,In a long and hungry lineThe paupers sit at the tables,For this is the hour they dine.And the guardians and their ladies,Although the wind is east,Have come in their furs and wrappers,To watch their charges feast;To smile and be condescending,Put pudding on pauper plates,To be hosts at the workhouse banquetThey've paid for—with the rates.

The full text for George Sims's "Christmas Day in the Workhouse" can be found at this link. But a better way to understand the poem is to hear it recited by the great American actor, Robert Cochran Hilliard (1857 – 1927), also known in his day as Handsome Bob.

|

| Robert Cochran Hilliard (1857 – 1927) Source: Wikipedia |

Hilliard recorded Christmas Day in the Workhouse,

lightly abridged to fit the time constraints of early records,

for Victor Records in Camden, New Jersey on 8 November 1912.

lightly abridged to fit the time constraints of early records,

for Victor Records in Camden, New Jersey on 8 November 1912.

Workhouses no longer exist in our modern era and most governments provide many different kinds of social welfare to people in distress. But I feel the Dickensian melodrama of Sims's ballad carries a poignant quality that resonates with our present time in a way that I don't think it would have had last Christmas. As this dreadful year 2020 draws to a close, everyone in the world has surely reflected on the immense challenges that face humanity. Poverty remains a serious issue, especially with the plight of unemployment, evictions, and privations brought on by Covid19. Even now with the miracle of vaccines, millions of people around the world will continue to suffer for many months from the consequences of this horrible scourge. If there is anything we need in this holiday season of 2020, it is more charity and good will to all mankind.

But back to Mr. Sims's canary.

George R. Sims wrote many observations about life in East London.

One of the places he described was the bird market on Sclater Street.

George R. Sims wrote many observations about life in East London.

One of the places he described was the bird market on Sclater Street.

"On Sunday nothing but bird-cages are to be seen from roofs to pavement in almost every house. At first you see nothing but the avenue of bird-cages. The crowd in the narrow street is so dense that you can gather no idea of what is in the shop-windows or what the mob of men crowding together in black patches of humanity are dealing in."

Surely this was the place where he acquired his pet canary.

Likely it was there that he saw

many birds that could whistle complicated melodies,

as since Elizabethan times London's bird sellers

had expertly trained warblers, canaries, black birds, etc. to sing.

I think that is what George Sims is doing in this photo.

Teaching his canary to sing

via a dictaphone or gramophone recording.

We can only speculate if the tune was Jingle Bells.