At first glance this image seems like a scene at any gentlemen's' club from a

century ago. A few young men in military uniform are relaxing in a salon or

library. There are assorted pictures hanging on a wall, newspapers and

magazines on a table, and along the back of the room is an upright piano.

Nothing unusual here.

Except for two things. Their clubroom is not resting on solid ground but is

actually afloat inside a battleship. And that piano is no ordinary musical

instrument but a complex self-playing piano with a pneumatic mechanism able to

reproduce music from cryptic rolls of paper.

These men were junior officers in the U. S. Navy and they had returned from a

voyage around the world. And during the trip this player piano gave them a

tiny bit of recreation whenever time permitted.

On this postcard we see a long line of the warships steaming through a choppy

sea. A caption describes it as the U. S. Battleship fleet leaving Hampton

Roads on its "around-the-World Cruise" and according to the back of the card,

most, if not all, of them had a military-issued player piano onboard. There

were 16 battleships in the fleet and they were all about to sail to South

America and then continue westward across the Pacific Ocean to Asia and

beyond. It was December 1907 and this expedition promised a peaceful display

of naval prestige, as this was a rare time with no eminent threat of war. So

someone decided it was appropriate for such a diplomatic mission to include

music too. The AUTOPIANO company was ready to help.

Uncle Sam's Choice

During the famous cruise around the world of the American Fleet nearly every Battleship possessed an "AUTOPIANO" for the amusement and education of the officers and crew. That these instruments needed little of no repairing after having been exposed to every climate, is more conclusive proof of the remarkable durability of the "AUTOPIANO" and of its ability to give musical enjoyment and great satisfaction under any conditions. The marvelous Autopiano gives pleasure to every member of the family because all can play it.

The Autopiano Is Sold By

J. N. Adam & Co.

Buffalo, N. Y.

To any one sending name and address of probable purchaser of

an AUTOPIANO at the The Autopiano Co., 12th Ave., 51st to 52nd St., New York

City, we will send set of postcards of warships carrying Autopianos.

The Autopiano Company of New York arranged for this naval connection to its

"marvelous" instrument as a marketing scheme to gain advantage over its

player-piano rivals. Dozens of different souvenir postcards of the fleet were

printed and used to solicit customers. My first image came from a postcard in

this series. It is possibly the only one that shows an interior shiproom and an Autopiano.

The full picture shows more plumbing pipes and steel rivets than usually found in hotel salons or gentlemen's clubs. The postcard is captioned:

Junior Officers Mess Room

U. S. S. Connecticut

This Autopiano when photographed

on May 12, 1911 had been in use

on this Ship over 4½ Years.

One the back is a full description of the battleship and a testimonial to

the Autopiano.

U. S. S. Connecticut (Battleship)

Displacement, tons 16,000. Speed, knots 19. Cost,

$8,000,000. Length, 450 feet. Beam, 76 feet, 10 inches.

Draught, 24 feet, 6 inches. Main Battery, 4 - 12 inch guns, 8 - 8 inch

guns, 12 7-inch guns. Secondary Battery, 28 Rapid Fire and Machine

Guns. Complement, 856 men.

Uncle Sam's Choice.

The AUTOPIANO on board the United States Battleship Connecticut,

Flagship of the Atlantic Fleet was and still is in the Junior Officers' Mess

Room as shown on this interesting picture.

This AUTOPIANO when photographed on May 14th, 1911 had been in

use for over four and a half years, and that it has more than proved its

worth is evidenced by the following letter from one of the Junior

Officers:

Napeaque Bay, Long Island, May 24th, 1911.

Mr. R. W. Lawrence, Pres., The Autopiano CO., N. Y.

Dear Sir:—

The AUTOPIANO purchased from you which has been in the possession of the Junior Officers' Mess for the past four and a half years, has given excellent service during that time. It has been used constantly but retains its good action and tone. Change of temperature and Climate does not seem to affect it. We are highly pleased with it, and it seems good for many years of service. Very truly yours,

(Signed) ELMER D. LONGWORTHY,

Midshipman, U. S. Navy.

Mr. R. W. Lawrence, Pres., The Autopiano CO., N. Y.

Dear Sir:—

The AUTOPIANO purchased from you which has been in the possession of the Junior Officers' Mess for the past four and a half years, has given excellent service during that time. It has been used constantly but retains its good action and tone. Change of temperature and Climate does not seem to affect it. We are highly pleased with it, and it seems good for many years of service. Very truly yours,

(Signed) ELMER D. LONGWORTHY,

Midshipman, U. S. Navy.

The Autopiano Is Sold By

E. B. Guild Music Co.

Topeka, Kansas

The U. S. S. Connecticut appears on another postcard in the Autopiano series in a sepia tone

illustration. The picture has a copyright 1904 by E. Muller. The Connecticut

was built in the Brooklyn NY Navy Yard and was launched on 29

September 1904. Exactly two years later in 1906 it was commissioned and

considered the most sophisticated ship in the US Navy.

|

|

Will's Cigarette card, Famous Inventions No. 23, Auto-Piano Source: New York Public Library Archive |

|

|

Sectional illustration of player piano interior action, 1909 William Braid White Source: Wikimedia |

Here's a schematic sideview

of the mechanism of a player piano.

of the mechanism of a player piano.

1. Pedal.

2. Pedal connection.

3. Exhauster (one only shown).

4. Reservoir; high tension

(low-tension reservoir not shown.)

5. Exhaust trunk.

6. Exhaust tube to motor.

7. Air space above primary valves.

8. Secondary valves.

9. Striking pneumatic.

10. Connection from pneumatic

to action of piano.

11. Piano action.

12. Pneumatic motor.

13. Trackerboard (music roll

passes over trackerboard).

2. Pedal connection.

3. Exhauster (one only shown).

4. Reservoir; high tension

(low-tension reservoir not shown.)

5. Exhaust trunk.

6. Exhaust tube to motor.

7. Air space above primary valves.

8. Secondary valves.

9. Striking pneumatic.

10. Connection from pneumatic

to action of piano.

11. Piano action.

12. Pneumatic motor.

13. Trackerboard (music roll

passes over trackerboard).

Player-piano music rolls were 11¼ inch wide and were mass produced by several companies that initially followed a standard format for playing only 65 notes. By 1903 one company had a catalog of over 9,000 titles. In 1908 the industry adopted a new standard with 88 notes, the same number of notes as on an ordinary piano. Newer player-pianos like the Autopiano were modified to accept this increased range.

_ _ _ _

The

Autopiano Company

was just one of hundreds of manufacturers of pianos, reed organs, and player

pianos that flourished in America at the turn of the 20th century. The

company was based in New York City and began operations in 1903 at a huge

factory that had 300,000 square feet of space and occupied two blocks along the Hudson River. Within a short time it was producing 10,000

instruments a year, all player piano types with pneumatic controls. The

company quickly established a reputation in the industry for making for a superior product that was robust in any kind of climate, dry or humid. Soon

it was exporting Autopianos to music lovers around the globe.

This postcard illustration gives a fanciful bird's eye-view of the Hudson

River in New York. A caption identifies it as "The Atlantic Battleship

Fleet passing the Autopiano Factories."

The card was never posted but on the back there is a message to Edith Lerris (?) from Myrtle

Brenner (?). Either Myrtle was only six years old or never mastered penmanship.

A note to

you

dont it

look it.

it is a dish

of honey

and cheese

for you

you

dont it

look it.

it is a dish

of honey

and cheese

for you

Even opera divas like

Luisa Tetrazzini

(1871–1940), pictured on this next postcard, endorsed the "marvelous

Autopiano—the piano that anyone can play." Tetrazzini was an Italian

coloratura soprano who performed in major opera houses around the world and became one of the highest paid artists of the early

20th century. The Italian-American dish, chicken tetrazzini, was named in her honor.

San Francisco, Cal.

The Autopiano Co., New York, N. Y.

The Autopiano Co., New York, N. Y.

GENTLEMEN:

The Autopiano is a blessing to humanity. It should be in every home, for it brings with it the culture and refinement which only the compositions of the great masters afford. I find I can play the great operas with the same feeling and expression with which I sing them. I love to play it—it is wonderful—there is no player piano to equal it. Faithfully yours,

Luisa Tetrazzini

The Autopiano is a blessing to humanity. It should be in every home, for it brings with it the culture and refinement which only the compositions of the great masters afford. I find I can play the great operas with the same feeling and expression with which I sing them. I love to play it—it is wonderful—there is no player piano to equal it. Faithfully yours,

Luisa Tetrazzini

Porch Brothers, Inc.

Johnstown, Pa.

Johnstown, Pa.

This second postcard of the Autopiano factories shows the building lit at

night with more battleships using searchlights out in the Hudson River. The

caption reads: "The Autopiano factories work over-time to supply the demand

for this marvelous Player Piano". I can easily imagine that a few navy midshipmen like Elmer D. Longworthy worked overtime too, acting as Autopiano Co. agents in foreign ports

|

|

Grant NE Perkin County News 26 February 1909 |

In 1906-07 as the Autopiano company began suppling the U. S. Navy with its

musical instruments, the navy was preparing its fleet for an historic

voyage around the world by order of President Theodore Roosevelt. The fleet consisted

of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with various smaller

escort and support ships. Eventually the expedition would have 30 ships in all, manned by 14,000 sailors. It was later given the nickname "The Great White

Fleet" because the ship hulls were painted white. The U.S.S. Connecticut was

the flagship of the fleet and probably got the best paintwork. The expedition began on December 16, 1907 and finished on February 22, 1909.

|

|

U.S.S. Connecticut (BB-18), circa 1906 Source: Wikipedia |

The mission of the

Great White Fleet

was largely diplomatic as the fleet would be paying courtesy calls to

ports of many countries. But President Roosevelt also intended it as a

display of America's new battleship fleet, demonstrating America's military prowess

and naval capabilities as a major power in a world that was dominated by colonial

empires. And the United States was the newest nation to join that club.

|

|

Map of the voyage of the Great White Fleet, 1907-1909 Source: The Internet |

This map shows the route that began and ended in Hampton Roads, the great harbor on the James River between Norfolk and Hampton, Virginia near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Notice that the fleet travelled around Cape Horn in South America as the Panama Canal was still under construction and would not be finished until August 1914. The placenames in red are where the fleet re-coaled the ships. Once it reached San Francisco, the fleet replaced two battleships before continuing across the Pacific.

As the result of the Spanish-American War and the annexation of Hawaii in 1898, the route included stops at the new U. S. territories of Hawaii, Samoa, Guam. and the Philippines. On its return leg the fleet took a short cut from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal, rather than going around Africa. The expedition took 14 months and covered 43,000 miles while making calls on twenty ports on six continents.

The

U. S. S. Florida (BB-30) was pictured on another Autopiano postcard. Like the postcard of the

U. S. S. Connecticut there was information about the ship on the back of the

card as well as a promotion of the Autopiano Company by the Orton Bros.

music store of Butte, Montana.

U. S. S. Florida (Battleship)

Displacement, tons 21,825. Speed, knots 21. Cost,

$6,000,000. Length, 521 feet, six inches. Beam, 88 feet, 2

inches. Draught, 28 feet, 6 inches. Main Battery, 10 - 12

inch guns, 16 - 5 inch guns. Secondary Battery, 10 Rapid Fire and

Machine Guns. Complement, 1014 men.

The Florida was larger and more powerful than the Connecticut but it was not

launched until May 1910 and was commissioned on 15 September 1911, so

this ship was not part of the Great White Fleet of 1907-09. Evidently the Autopiano Company profited by this kind of patriotic advertising and expanded its promotion into the next decade.

I should also note that many crews of the battleships included a navy band. I've written a story about photos of two of them, including the Florida, in The USS Florida and USS Arkansas Navy Bands.

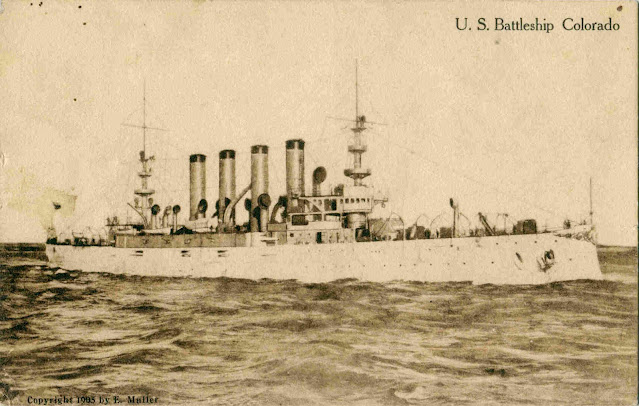

The Autopiano battleship series included a picture of the U. S. Battleship

Colorado, also known as

Armored Cruiser No. 7, which also did not accompany the Great White Fleet in 1907-09. In

November 1916 while being overhauled the ship was renamed Pueblo, in

order to free up her original name for use by a newer bigger battleship

Colorado. This card promoted sales of the Autopiano by a music dealer, J. H. Troup, of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Likewise this next ship, the Protected Cruiser

"New Orleans" (CL-22) was not part of the Great White Fleet either but supposedly still had an

Autopiano onboard. It was a much smaller and older ship than the previous

battleships. Commissioned in March 1898, the ship was immediately put to service in

Cuba during the Spanish-American War and later was assigned to the Asiatic

Fleet in Manila, Philippines. The back of the card offered Autopianos sold by Weiler Bros., of Quincy, Illinois.

The next battleship in the Autopiano series was the U.S. Armored Cruiser

New York (ACR-2) which also wasn't a ship in the Great White Fleet. Perhaps this

was because of its age as its keel was laid in 1890 and at the time of the

1907-09 expedition the New York was laid up for an extensive refit that was

not finished until 1909. Presumably it then got a new Autopiano too. Maybe purchased from W. H. Rider of Kingston, New York.

Another in the Autopiano series was the Armored Cruiser

St. Louis (CA-2)

which was launched in 1905 but was already stationed on the west coast in

1907 when the Great White Fleet left on its voyage. The St. Louis was built

for $2,740,000 which seems a bargain, especially because a top of the line

Autopiano cost $600 then. The recipient of this postcard might have got a better deal from the J. E. Lothrop Piano Co. of Dover, New Hampshire.

Finally I finish with the U. S. Battleship Wisconsin (BB-9)

which did join the Great White Fleet in 1908 for the second leg of its

voyage when it switched with the U.S.S. Maine in San Francisco. This

Illinois-class battleship was launched in November 1898 and commissioned on

4 February 1901. This postcard encouraged music lovers to get a marvelous Autopiano from the Yahrling-Raynar Piano Co. of Youngstown, Ohio.

|

| 1912 Pacific Medical Journal |

In 1912 the Autopiano company claimed it had instruments on seventy five ships of the U. S. Navy and that 30th regiment U. S. Infantry had taken 20 Autopianos to Alaska. Even the Pope had an Autopiano in the Vatican. (Which brings to mind an odd image of his Holiness sitting on a piano bench vigorously pumping his legs to sing along to the latest music roll, presumably a hymn tune.)

In 1917 the Autopiano Company installed its instruments in over 100 army training camps as America prepared to join the war in Europe. The company was one of the largest producers of musical instruments which were known for being reliable and expressive devices for playing music. But all the player-piano companies were competing against another medium that was rapidly gaining strength. The 78rpm gramophone record.

In several ways a gramophone/victrola and a player-piano were alike. Both were mechanical marvels that produced music on demand from prerecorded performances. Both used a special media, a disc or a paper roll, that encoded the music invisibly. Both were promoted by famous composers, song writers, and musicians. Both became enormously popular creating a consumer demand that turned music into a consumable commodity which resulted in thousands of new titles produced every week. And as Autopiano advertising boasted, both player-pianos and gramophones required no musical skills and could be played by anyone.

The big differences between the two mediums was that a player-piano like the Autopiano required continuous physical action by a human to play music, while a gramophone needed only minimal effort to crank the motor spring and set down the needle. But more crucial difference was that a gramophone record reproduced the exact sound of voices and instruments while a player-piano just sounded like a like a piano.

My first experience of music came from a little black and tan RCA 45rpm record player that my mother let me play using a stack of records she must have acquired when she was in high school and college. A few years later my dad got hooked by the hi-fi stereo craze and I discovered jazz, opera, and orchestral music on 32rpm discs. Soon I began buying my own records and still have a large collection though I admit I rarely listen to them. I try not to think about the crypt that stores my collection of cassette tapes since I no longer have a machine that can play them.

When compact discs first came out in the 1980s everyone was amazed that they were so small and light weight, compact as they say, compared to the heavy albums of vinyl records. Yet today, 40 years after buying my first CD, I've thrown away most of the clunky boxes that they came in and store my CDs in clear plastic envelopes. Unfortunately I can't use them in my car anymore as the "entertainment center" can't play them. Instead I've converted—ripped countless music albums from CDs into digital files on a flash drive. This means that most of the time I don't know the title of a song or the name of the artist performing. How do you turn off random shuffle play? Now even flash-drives are old fashioned. Who needs messy digital files when music can come straight from the Spotify or Apple clouds.

The average lifespan of the seven battleships used to promote the Autopiano was about 27 years, skewed by the cruiser New York lasting 42 years. Despite their size, or maybe because they were so immense, battleships were not built to last and all these ships ended up being cut up for scrap long before the start of the next war. I wonder if those Autopianos were saved from demolition.

The Autopiano company endeavored to remain independently solvent but in the 1920s it was bought by the Kohler and Campbell piano company. The new owners continued manufacturing player-pianos into the 1930s but like many businesses that depended on consumer demand, it was unable to survive the Great Depression and closed its Autopiano factory forever. Everyone was listening to the radio anyway.

But once upon a time, young navy midshipmen tapped their feet and swung to music on the rolling sea as they sang along to music coming from the marvelous, fantastic Autopiano. Did the company supply them with enough music-roll titles? How many times did they listen to the same tune on a trip around the world?

To demonstrate the sound and machinery of a player-piano

here is a video of a 1905 Autopiano Player Piano, made of white oak,

here is a video of a 1905 Autopiano Player Piano, made of white oak,

that was beautifully restored by the craftsmen at

Pianosnthings.

Notice how the little levers under the keyboard control the music

and the foot pedal action almost turns the Autopiano

into some kind of fitness equipment found at a gym.

Notice how the little levers under the keyboard control the music

and the foot pedal action almost turns the Autopiano

into some kind of fitness equipment found at a gym.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where music sometimes comes in a sepia box.