This is a drummer with an attitude.

He looks confident, even cocky, because he knows

his drumsticks keep the band on the proper beat.

That kind of bold self assurance is not typical

of a boy who might be at best 10 years old.

He looks confident, even cocky, because he knows

his drumsticks keep the band on the proper beat.

That kind of bold self assurance is not typical

of a boy who might be at best 10 years old.

His fellow musicians on piccolo and trumpet seem less certain,

maybe a bit apprehensive. Both boys need to know the tunes

because the sound of their instruments

will always be easily heard.

maybe a bit apprehensive. Both boys need to know the tunes

because the sound of their instruments

will always be easily heard.

A young horn player gazes off into the distance.

He might be age 11 or 12 but his poise

shows the maturity of a musician who knows his instrument.

He might be age 11 or 12 but his poise

shows the maturity of a musician who knows his instrument.

The other wide-eyed horn player — maybe not so much.

One of the first lessons that brass players learn

is to keep a firm grip on your horn and not drop it.

His mates on trumpet and piccolo are aged 7 or 8,

surely not more than 10.

One of the first lessons that brass players learn

is to keep a firm grip on your horn and not drop it.

His mates on trumpet and piccolo are aged 7 or 8,

surely not more than 10.

The rest of the band are older, around 12 to 15.

The bass trombonist might be 16.

All the brass instruments have rotary valves

which were the common design for central European brass bands.

The bass trombonist might be 16.

All the brass instruments have rotary valves

which were the common design for central European brass bands.

Every boy wears a smart military uniform

with a tall shako hat and collar badges of a musical lyre.

Two men sit in the center, a younger man with a trumpet,

and an older man dressed in a lighter colored coat,

whose stout baton embellished with silver bands,

and fierce upturned mustache marks him as the bandleader.

with a tall shako hat and collar badges of a musical lyre.

Two men sit in the center, a younger man with a trumpet,

and an older man dressed in a lighter colored coat,

whose stout baton embellished with silver bands,

and fierce upturned mustache marks him as the bandleader.

This is not an ordinary school band.

The tasseled lyre, or glockenspiel in German,

was a special instrument associated with military bands.

These boys are like cadets, or army bandsmen in training.

The tasseled lyre, or glockenspiel in German,

was a special instrument associated with military bands.

These boys are like cadets, or army bandsmen in training.

But from where?

{click the images to enlarge}

The answer is – somewhere near Budapest.

This postcard photo was postmarked from there

but the date is partly illegible. If it follows the

date style of Hungary with year/month/day

then it was mailed 1912 JUL 1.

This postcard photo was postmarked from there

but the date is partly illegible. If it follows the

date style of Hungary with year/month/day

then it was mailed 1912 JUL 1.

There are several names scrawled in the message side,

and in the center is another date 1912 Jun 30

which corresponds well with the postmark.

and in the center is another date 1912 Jun 30

which corresponds well with the postmark.

Do the signatures belong to some of the boys in the band?

I can't really say. But it seems fair to say this wind band

is a group of young Austrian-Hungarian boys

from two summers before the onset of World War 1.

I can't really say. But it seems fair to say this wind band

is a group of young Austrian-Hungarian boys

from two summers before the onset of World War 1.

That might be the end of this story except that in my research,

I stumbled across a small thumbnail image on the internet.

It's the exact same photo including even the signature.

I stumbled across a small thumbnail image on the internet.

It's the exact same photo including even the signature.

|

| Die Schilzony-Kapelle 1909 [Robert Rohr] Source: www.dvhh.org [Dead Link] |

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, or Austria-Hungary as it is more properly called, was a union from 1867 to 1918 of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, often referred to as the Dual Monarchy under Kaiser Franz Josef. In German it was abbreviated to k.u.k. – kaiserlich und königlich for Imperial and Royal. The empire encompassed hundreds of different cultural, religious, and national groups. Though German was the official language, there were many others within this vast nation. This colorful map shows the mixture of Austria-Hungary's principal ethnic populations in 1910 when the photograph of the boys band was taken. I've marked the small town of Billed in the Banat district near the southeast border. Today the town is part of Romania.

|

| Ethnic Groups of Austria-Hungary, 1910 Source: Wikimedia |

Niklas Schilzonyi was evidently a very gifted musician, whose talent was recognized at an early age when at just 13 years old he was appointed bandmaster of a state military band. He developed a music academy in Billed where in 1897, he secured permission, and possibly sponsorship, from the Kaiser to take his boys' band, a Knabenkapelle in German, on a grand tour of the United States. The band had 40 musicians from the Billed, Banat area and they presented concerts as Kaiser Franz Josef's Magyar Hussaren Knabenkapelle — The Hungarian Boys' Military Band. Surprisingly the first city to promote them in the US was San Francisco in August 1897.

This poster, found on a biography of Schilzonyi at www.heimathaus-billed.de, comes from that 1897 tour and shows the boys dressed in splendid blue and red uniforms embellished with fancy embroidery, cloaks, and plumed hats. Schilzonyi stands on the right and a vignette of his portrait is in the top left corner.

|

| Schilzonyi and his famous Hungarian Boys' Military Band Source: Danube Swabian Biographies [Dead Link] |

The band boys ranged in age from 7 to 15, and traveled with a tutor named Michael Nussbaum who provided them with a regime of proper scholastic study. In the afternoons, Schilzonyi gave the band its musical training. In October 1897, the San Francisco Call newspaper published a delightful story describing the military precision needed to organize 40 boys into a musical band representing Austria-Hungary. This illustration of the drum major and a little drummer was taken from that article.

|

| San Francisco, CA Call17 October 1897 |

By November 1897, the Hungarian Boys' Military Band had moved onto southern California to give concerts. The cartoonist with the Los Angeles Herald sketched the boys in rehearsal. The sunny climate and plentiful oranges must have agreed with the boys as they stayed through the winter into 1898.

|

| Los Angeles, CA Herald 14 November 1897 |

The tour continued into the next year with July concerts in Kansas City, MO.

|

| Kansas City, MO Journal 25 July 1898 |

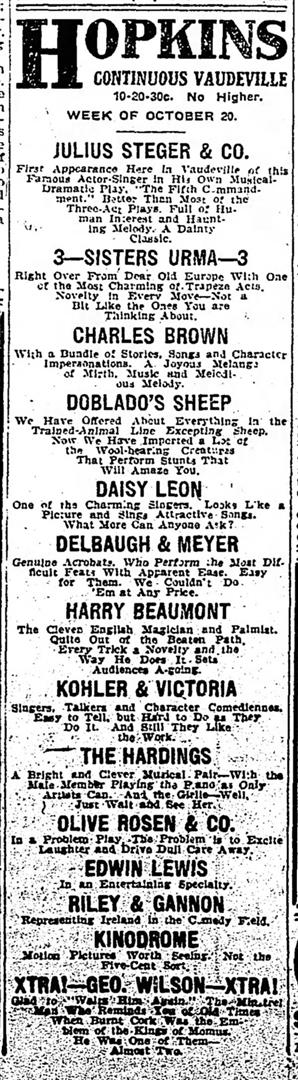

By the third year on tour, the band dropped any reference to Kaiser Franz Josef, and instead called themselves Schilzonyi's Hungarian Boys' Military Band. The advertisements for concerts in New Orleans praised their music as of the highest order. But the concerts were often booked for fairs or vaudeville theaters where they competed with all kinds of distracting novelties and entertainments.

|

| New Orleans, LA Times Picayune 05 August 1899 |

|

| Brooklyn, NY Daily Eagle 28 January 1900 |

By January 1900, Nikclas Schilzonyi's band of Hungarian Boys were in New York City. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle included a sketch of Schilzonyi with its report, which notes that their hometown was Billed, Hungary. The band's musical repertoire consists of over 500 pieces of music of the most difficult kind.

The band gave performances in Rochester, NY in February 1900 where a reviewer noted that the concert was limited to 50 minutes due to the youth of its musicians. The program included a Hungarian march composed by Schilzonyi; the popular overture to Mignon by Thomas; Sousa's Star and Stripes march; and ragtime music, Georgia Camp Meeting.

At this point Schilzonyi probably took his band back home to Hungary, as references to their concerts disappear. After three years some of his musicians had likely reached the age for real military service. It may have been time to get newer and fresher kids for the band.

But Schilzonyi was not gone for very long. In November 1904 his band returned to Syracuse, NY.

This second tour would last until 1909.

* * *

Over the next 5 years, Niklas Schilzonyi's Knabenkapelle Hungarian Hussar Band played Boston; Pittsburgh; Chicago; Washington D.C.; Harrisburg, PA; Portland, OR; Vancouver B.C., and Winnipeg, Manitoba. The band's size occasionally changed, sometimes 30, as many as 50, but usually about 35. They were not always the headliner as they often toured as an act within a traveling minstrel show. Steady summer work came by playing a couple of weeks at an amusement park, with two, sometimes three, shows a day. But novelty wears thin and Schilzonyi's band would have to move on to another city.

|

| Winnipeg, Manitoba Tribune 02 March 1907 |

|

| Winnipeg, Manitoba Tribune 02 March 1907 |

They were a big hit at Winnipeg's Bijou Theater, as the booking was extended another week. A reviewer praised the youthful musicians who displayed marvelous ability as executive artists, and their playing is of a very high order of excellence. The tone masses are powerful and effective and the unity of attack extraordinary.

The Monday program, it changed each day, was:

- Autro-Hungary Armee March.

- Poet and Peasant, by Suppe.

- Sextette from Lucia da Lammermoor, by Donizetti.

- Second Regiment, March Militaire.

- Eight Fanfare, Trumpet solo.

* * *

|

| Winnipeg, Manitoba Tribune 02 March 1907 |

The last report of Niklas Schilzonyi's Hungarian Boys' Military Band was a set of concerts in November 1909 at the Chutes amusement park in San Francisco. Again it seems likely that the band had overstayed America's enthusiasm for Hungarian boys' bands and it was time for them to return home to Billed, Hungary.

However the biography of Schilzonyi has a newspaper clipping that shows he was in Reno, Nevada in April 1912, performing as a "quick change artist" impersonating several great composers. He applied for citizenship in 1913 and took residence in Whittier, CA near Los Angeles. He remarried and had children born in California. After the war years, he changed his name from Schilzonyi to Schilzony, but continued to teach music and direct bands. He took out patents for an invention of a double bore clarinet. In 1927 his family life came apart and he divorced, moving to the east coast. His name was found in the 1940 census for New York City, but the date of his death is not known.

So because the postcard's 1912 date seems in conflict with what is known of Schlizonyi's life history, I can't say with complete certainty that my postcard photo of a Knabenkapelle is Niklas Schilzonyi's boys' band. It's quite possible that the identification of this photo on the Danube Swabian biography of Schilzonyi was in error. A big handlebar mustache does make a very good disguise. But the photograph may date from earlier, perhaps in the period between 1900 and 1904 when he was back in Hungary recruiting a new band. Who knows for sure, one hundred years after the camera took the photo?

But for my purpose it does not matter. The postcard of the cryptic Hungarian boys band and the story of Niklas Schilzonyi are both perfect examples of one of Hungary's signature exports – musicians. Before the tragic events of 1914 intervened, the US tour of Schilzonyi's Boys' Band introduced America's youth to a level of extraordinary Hungarian musicianship that surely inspired boys from San Francisco to New Orleans to New York to aspire to play a band instrument. And as I've tried to show in the deconstruction of the postcard, the proud expressions of those young boys are of skilled musicians who knew how to play music.

To prove my point, this is only part one of my story on Hungarian Boys Bands.

Next weekend I'll have more.

Next weekend I'll have more.

My other stories in this series are:

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where other boys play marbles.

where other boys play marbles.