It's the directness of his gaze that captures our attention.

His eyes look straight into the camera lens

which fixes the moment with wonderful clarity.

His carefully groomed hair and chin beard

give him an air of a pious but genteel man.

The purple coloring of his bow tie,

crudely dabbed on by the photographer,

suggests an affable or even a debonair nature.

But it is the flute resting on his thigh

that adds an unusual refinement of culture

to this man's portrait.

The flute is made of African blackwood or possibly South American rosewood, which were traditional materials for a premium flute in the early 19th century, as well as the standard woods for oboes and clarinets today. This woodwind instrument has only a few simple keys for the player's fingers, and comes apart in five sections, but is otherwise no different from how flutes of the Medieval and Renaissance eras were made. By the 1850s, most professional flutes were fitted with a more sophisticated key mechanism, so this flute's less complicated fingering system would be more suited for playing popular music rather than more chromatic symphonies and operas. Generally the fife and piccolo with their high treble voice were used in bands, while the flute's quieter timbre was better suited to performances in theaters.

As the man is holding a musical instrument, it may indicate his trade as much as any amateur interest in the flute. Singing teachers often displayed an instrument, so he may be a choral music teacher rather than a member of a band or orchestra.

Between 1855 and 1875, early American photographers made thousands of small photographs like this, called

carte de visites, or CdVs. Unlike the first daguerreotype photographs, they were inexpensive to produce, but more importantly they were easy to reproduce as duplicates. Everyone had to have one, and the trade of photographer became the new tech entrepreneur of the 19th century.

Though much improved from the lengthy time needed to make daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, the photo process still required a several seconds to expose the negative plate, so subjects had to remain as immobile as possible for the best photo. One way to make people comfortable was to have them sit in a special chair with a padded fringed arm rest, the standard furnishing for any early photographer's studio. Likewise the drapery hung behind the subject was a very common prop in these early photos. I suspect it was a style left over from painted portraiture adding an element of texture and shape to the plain whitewashed walls of the studio set.

The photographer's backstamp shows a medallion:

National Gallery

Mills & Son

Photographers

Main St. Penn Yan, N.Y.

Penn Yan is a small village in west New York state at the top of Keuka Lake, one of the Finger Lakes. The photographer sometimes used the label -

Dr. Mills. I have seen other examples of Mills cdv's which have a tax stamp affixed to the back which dates the photos to the Civil War years 1863 to 1865. In 1860 Penn Yan had a population of 2,388, but its next census of 1870 recorded 3,488 citizens, an increase of 46.1%.

***

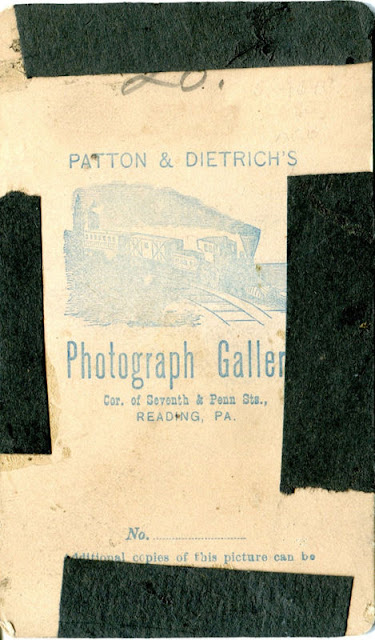

This flutist belongs to a group of musicians from Reading, PA that I featured in a story from 2011,

Uncle Fred Wagner and Friends. He is dressed in a formal tail coat with lapels nearly as wide as my first 1970's tuxedo. His CdV was made by the same photographer that took photos of Uncle Fred and three other musicians, so I presume that they all went down to the studio for a photo with their instrument in order to commemorate an occasion. Perhaps an anniversary of the start of their orchestra, or maybe to make a collective a souvenir for a departing musician. I hope to discover more Reading musicians so I can put the band back together again.

The back of the CdV has the photographers' name

with a woodcut image of a smoking steam engine train:

Patton & Dietrich's

Photograph Gallery

Cor(ner) of Seventh & Penn Sts.

Reading, PA.

Like the first CdV, this studio was active from around 1860 to 1875. I estimate that this set of photos was made after the war, around 1870.

The gentleman's flute is also made of blackwood, but it has an ivory headjoint where the embouchure hole produces the flute's sound. Elephant ivory was once a common material used for woodwind instruments, as it is very stable when damp and yet has plastic properties that allow it to be turned to exact dimensions. The instrument also has a complex key mechanism which marks it as an orchestral flute.

***

There are numerous unknown musicians in my photo collection who sadly left no useful clues as to their name, place, or time. This serious looking flutist is one of them. His studio photo was printed as a postcard so he comes from a later generation, perhaps 1900 to 1920. The postcard message/address is divided but lacks any clues for its country of origin, so he might be American, or Canadian, or British. Dressed in fine formal wear with starched white shirt and stiff collar with black bow tie, he has an authentic appearance of a professional musician. Perhaps he had his photo taken to celebrate his appointment to an orchestra.

Again his flute is made of African blackwood including the headjoint. The keys, I think, are of a higher level of woodwind design than the previous flute, but as my expertise lies with brass plumbing, I will not venture into the arcane details of flute fingering systems.

What is interesting is that tucked under his left arm is a piccolo, also in blackwood. Most flute players learn to play a piccolo just in order to play John Philip Sousa's

Stars and Stripes Forever march, a popular encore on music programs ever since its 1896 premiere. But in an orchestra the piccolo player is a very special soloist, capable of obliterating an entire brass section with blistering fast runs of high notes. Usually their position is designated as third chair flute/solo piccolo, with the flute as their secondary instrument, used as needed. Therefore I've decided this sober fellow with a neatly trimmed mustache holds the third flute/piccolo seat in a proper opera or symphony orchestra.

***

Our fourth flute is held by this young lady who also posed for a studio photographer. It is a 4"x6" photo print sized a bit larger than a postcard. Dressed all in white from the bottom of her shoes to the bow in her hair, she sits on a faux garden bench in front of a painted pastoral backdrop. Her age is more than 13, I think, but surely no more than 18 years old. Again this photo is of another anonymous musician, as there is no name or date or place. The best clues are her hair bow and dress length, fashions from around 1905 to 1920.

The girl's flute is a hybrid model with a blackwood body and a silver headjoint. By the early 20th century, flutes were made in two styles, one in wood, and the other in metal, principally silver. Some manufacturers tried to get the best of both by combining a wood body with and a metal headjoint. But the true woodwind flute was on the decline.

Silver flutes produce a brilliant color of sound, whereas blackwood flutes evoke a different sonic hue that makes a warmer whistle. Wooden flutes however are heavy, sensitive to temperature change, and prone to cracks, while metal flutes are lighter, stable, and less influenced by the humidity of the player's breath. Consequently in our modern time, the silver, and sometime even gold, flute has become the dominate style for flutists in orchestras and bands.

Did this young girl aspire to be a professional musician?

All we can know is that she had a beautiful smile.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where mill wheels always turn out the best in vintage photos.