Subject, Place, and Singularity.

Those are the qualities that make

a premium collectable photograph.

Those are the qualities that make

a premium collectable photograph.

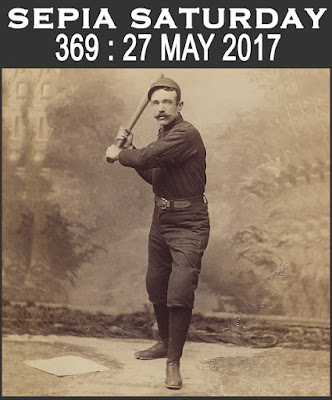

The unusual subject here

is a gentleman holding a bassoon,

an instrument rarely seen

in cabinet card portrait photos.

The curious singularity

is his magnificent long mustache

curled like the bocal on his instrument.

But it is the unexpected place

where the image was taken

that makes this a unique photograph.

Australia.

is a gentleman holding a bassoon,

an instrument rarely seen

in cabinet card portrait photos.

The curious singularity

is his magnificent long mustache

curled like the bocal on his instrument.

But it is the unexpected place

where the image was taken

that makes this a unique photograph.

Australia.

The man sits in a relaxed pose,

cross legged on a low chair,

gazing to his right.

He is dressed

in formal white tie and tail coat,

with a boutonniere on his lapel.

His oiled hair is short

and carefully groomed,

and his imperial style mustache/beard

gives him a debonair almost rakish air.

His bassoon lays diagonally

at rest across his thigh

showing the double reed, bocal, and keywork

but not the bell.

cross legged on a low chair,

gazing to his right.

He is dressed

in formal white tie and tail coat,

with a boutonniere on his lapel.

His oiled hair is short

and carefully groomed,

and his imperial style mustache/beard

gives him a debonair almost rakish air.

His bassoon lays diagonally

at rest across his thigh

showing the double reed, bocal, and keywork

but not the bell.

It is the work of a skilled photographer,

Instantaneous Portraits

Falk

496 George St. Sydney.

Instantaneous Portraits

Falk

496 George St. Sydney.

Australia.

In the 19th century Australia did have very fine photographers in the big cities like Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth, and vintage Australian photographs can be found on the American antique market, though not in any great number, usually dozens rather than hundreds. This musician's portrait was taken by Melbourne-born photographer Henry Walter Barnett (18620–1934) who trained in London. In 1887 he returned to Australia and opened Falk Studios on George Street, Sydney where he became renown for his photo artistry, and expensive fees. Ten years later Barnett left for London again to establish an upscale portrait studio at Hyde Park Corner where his customers included the royal family and prominent members of English society. With Barnett's studio work so well documented, it seems safe to date this gentleman's cabinet card in the decade from 1887 to 1897. Yet clearly he paid handsomely for a quality photograph from a leading Sydney photographer.

There is no marking on the photo's back. No studio imprint, no name or date. If the man played the violin or cornet it would not be an unusual photo, but it is his bassoon, the bass instrument of the woodwind family, and the fact that he is in Australia that makes this a remarkably rare vintage photo. Australia is a very big place, but in the 1890s its population was proportionately very small, and well-dressed bassoonists could only be a very, very small fraction of that number.

So how many bassoonists got their name in an Australian newspaper?

In the 1890s?

Not surprisingly, very few.

But curiously one bassoonist

was mentioned more often than expected.

Not surprisingly, very few.

But curiously one bassoonist

was mentioned more often than expected.

|

| Sydney Morning Herald 10 October 1891 |

In October 1891 the Sydney Morning Herald ran an advertisement for a Grand Invitation Matinee Concert given by Signor Angelo Casiraghi, cerrtified teacher of Violin and Harmony from the Conservatoire of Music, Leipzig. The afternoon concert included violin solos by Signor Casiraghi, several vocal numbers, a few works for orchestra, organ and harp, and two bassoon solos. performed by Mr. Phil Langdale (late Soloist of the Cowan Orchestra). The titles, "Lucie Long" and "Carnival de Venise" were arrangements made by Mr. Langdale of popular tunes set with variations.

The National Library of Australia is a wonderful historic archive with a free searchable newspaper database. Between 1888 and 1896 there were over 225 citations of "Phil Langdale, bassoon". Even for a noted violinist or pianist of this era this would be an exceptional amount of newspaper coverage.

But Mr. Langdale played the bassoon.

|

| Melbourne Argus 16 October 1888 |

The reference to "late Soloist of the Cowan (sic) Orchestra" was to the orchestra employed for the 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition. This event was organized to celebrate a century of European settlement in Australia. It was held at the Royal Exhibition Building which was built for the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880–81. For this earlier world's fair the western nave of the main building had a specially built orchestral platform complete with a grand pipe organ, and enough choir tiers for 700 to 750 voices.

Event organizers for the 1888 Centennial Exhibition anticipated that this concert feature would be a major attraction, so in 1888 they engaged the services of Frederic H. Cowen (1852–1935), a well-known British pianist, conductor, and composer. In 1888 he had just been made conductor of the Philharmonic Society of London, succeeding the famous composer Arthur Sullivan. His fee to go to Melbourne for the Centennial Fair was £5,000, an amount considered at the time especially extravagant for any musician. His terms included the hiring of 15 principal musicians from Britain for the Exhibition Orchestra. One of those musicians was the bassoonist Phil Langdale.

On the 15th October 1888 a smaller group of the orchestra presented an afternoon recital of solo pieces. On the program was an Air, with variations for bassoon, by F. Godfrey and played by Mr. Phil Langdale. Most of these fine solo performances were re-demanded and repeated, and the whole musical performance was found to be full of interest.

* * *

|

| Melbourne Australasian 4 August 1888 |

The Centennial International Exhibition opened in Melbourne on 1 August 1888 and continued to 31 January 1889. Frederic Cowen's exhibition orchestra numbered 73 musicians, including Signor A. Casiraghi in the first violins and P. Langdale, principal bassoon.

|

| Orchestra musicians roster for the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne: 1888–1889 Source: Official Record |

The 15 principals imported from Britain with Mr. Cowen were paid £10 per week. The exhibition commission also agreed to defray the cost of a second-class ticket for the steamship voyage to Australia and a return ticket, if desired. In 1888 the estimated travel time from London to Sydney was 50 days. The remainder of the orchestra was hired from musicians resident in the Australian Colonies. Their salaries varied from £3 10s to £12 per week. The 708 men and women in the Exhibition Choir sang for gratis—without pay, though they got free passes into the Exhibition.

|

| Orchestra musicians' pay rate for the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne: 1888–1889 Source: Official Record |

The Exhibition ran for a bit over 26 weeks during Australia's spring and summer seasons. Over the course of the festival the orchestra and choir performed for 211 Orchestral, 30 Grand Choral, and 22 Popular concerts under Mr. Cowen's direction. This is in addition to many vocal, piano and instrumental recitals, and countless concerts of military bands that provided music throughout the rest of the exhibition area and amusement park.

|

| Concert hall and grand organ for the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne: 1888–1889 Source: Official Record |

Among the Grand Choral works were two performances of Beethoven's Choral 9th Symphony; four of Händel's "Messiah" oratorio; two of Haydn's "Creation" oratorio; four of Mendelssohn's "Elijah" oratorio; two of Rossini's "Stabat Mater"; and twelve performances of Cowen's choral music, his "Ruth" oratorio, "Song of Thanksgiving", and "Sleeping Beauty" cantata.

|

| List of choral works performed at the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne: 1888–1889 Source: Official Record |

The orchestral concerts included the remaining eight Beethoven symphonies; Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique; Brahms' Symphony No. 3; Liszt's "Les Preludes"; Mendelssohn's Sym. No. 3 "Scotch"(sic), Sym. No.4 "Italian", and Sym. No. 4 "Reformation" Symphonies; two Schuber symphonies; and three Schumann symphonies. Nearly all were performed more than once. Beethoven's 6th Symphony the "Pastorale" was played five times. The programs also included an astonishing number of overtures, 91 opera overtures including nearly all of those by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Rossini, Schubert, Wagner, and Weber. There were also a few violin concertos and several piano concertos, along with numerous incidental pieces, opera selections, songs, ballets, marches, rhapsodies, ballads, and serenades.

Quite a lot of this music was new and unfamiliar to both musicians and Melbourne's audience. For example Brahm's 3rd Symphony only had its premiere in December 1883. Over 50 musical works programed on concerts at the 1888 Centennial International Exhibition were first performances for Melbourne and probably for Australia too.

Concerts were scheduled twice a day at 3:00 pm and 8:00 pm, six days a week except on Sunday. Presumably mornings were reserved for rehearsals. That's roughly 7 to 8 hours of music making each day, or 36 to 48 hours a week not counting individual practice time. In comparison, modern orchestra musicians typically work a 20 to 24 hour week.

|

| List of orchestral works performed at the Centennial International Exhibition Melbourne: 1888–1889 Source: Official Record |

The Melbourne Exhibition Hall was modified to seat 2,500 people. Over the six months that the exhibition was open, an average of 1,915 tickets were sold for each concert, making a total attendance of 467,2999. Of course, there were many other non-musical activities and sights for the public to see at the Melbourne exhibition park. but the musical arts were the chief attraction. It made for a daunting, if not exhausting, marathon list of music for any musician. For bassoonist Phil Langdale it meant easily a half dozen difficult bassoon solos to master each day. Only a well trained musician could survive that level of intense music. Someone who knew how to wield a bassoon as a defensive weapon if the music so demanded.

Someone who had been a member

of Her Majesty's Cold Stream Guards Band.

of Her Majesty's Cold Stream Guards Band.

|

| Dublin Irish Times 13 April 1875 |

The Coldstream Guards Band had a long musical tradition that dated back to 1785, and it held a reputation as one of the best in the British Army, which had a great number of military bands. This band provided music for any ceremonial duties to Queen Victoria, as well as for other military events. But by the 1870s, military bands also were an important unit for the British government's public relations, traveling the country performing at innumerable flower shows, exhibitions, and civic affairs. Between 1873 and 1881 there were over a hundred newspaper references to Mr. Langdale's bassoon solos (with variations) at concerts by the Band of the Coldstream Guards. The band's programs were regularly published and Langdale's bassoon received much praise in the reviews. The music that the band played included an immense number of popular overtures, songs, and solo instrumental works arranged for wind band from orchestral scores, as well as the standard military marches. This disciplined musical training would have given young Philip Langdale a good grounding in all the current styles of European music.

After 1881 his name appears less often as he seems to have left the Coldstream band for civilian life. In July 1883, Mr. P. Langdale appeared at London's Adelphi Theatre playing a bassoon solo "Lucy Long". In February 1885 another Langdale bassoon solo was advertised by Her Majesty's Theatre where an orchestra of 100, assisted by the Band of the London Rifle Brigade, played a concert of various opera overtures, solo vocal pieces, dances, and a Descriptive Fantasia: "A Voyage in a Troop Ship." In July 1885, Mr. Langdale demonstrated a bassoon made of ebonite, a man-made material, at a musical instrument exhibit of the Rudall, Carte, and Co.

But the only thing that this research proves

is once upon a time a talented British bassoonist

could boast of a surprising prestige

on the Victorian era concert stage.

It doesn't convincingly establish that

the bassoonist with the wonderful curled mustache

is Mr. Phil Langdale, the late bassoon soloist

of the Melbourne Exhibition Orchestra.

is once upon a time a talented British bassoonist

could boast of a surprising prestige

on the Victorian era concert stage.

It doesn't convincingly establish that

the bassoonist with the wonderful curled mustache

is Mr. Phil Langdale, the late bassoon soloist

of the Melbourne Exhibition Orchestra.

If only there was another photo.

* * *

The 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition was an international exposition attracting elaborate displays from all around the world as well as Australia. Thousands of representatives of industry, trade, and the arts booked space at the exhibition to demonstrate their newest and best products. The planning also required hundreds of contractors and staff to operate the fair's activities. Concerned about maintaining security the Melbourne Exhibition Commission decided to have individual photo portraits compiled of all persons employed at the exhibition. Many of these identity photos survive in the archives of the State Library of Victoria.

The musicians of the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition Orchestra worked 6 days a week through the entire event, so of course, they were photographed too. The State Library of Victoria has a souvenir collage of the orchestra with 68 musicians' ID photos surrounding a photo of their music director, Frederic H. Cowen. There are no instruments and no names, but the archive offered a high definition image to download.

|

| 1888 Centennial International Exhibition Orchestra Paterson Bros., photographers Source: State Library Victoria Archives |

The musicians' photos, all men of course, illustrate the amazing variety of mustaches, beards, and hair styles that were the male fashion of the 1880s. This era might better be called the golden age of barbers.

The faces of many men were easily eliminated as too old, too fat, etc. But a few grainy images made promising matches. These two men, center row, 2nd and 3rd from right bear a good resemblance to my bassoonist, and the one on the left has a similar impressively long mustache.

This man, third row from bottom, 2nd from left, has a similar imperial style beard and a receding hair line.

But the man pictured on the bottom row, 4th from right, made the best match to my bassoonist.

His mustache may lack the twirled extensions but it has the same shape.

I think his hooded eyes, high forehead, thin hair, and cheekbones

makes him a ringer for the man in my photograph.

The two men also share an inclination for rumpled suit coats.

His mustache may lack the twirled extensions but it has the same shape.

I think his hooded eyes, high forehead, thin hair, and cheekbones

makes him a ringer for the man in my photograph.

The two men also share an inclination for rumpled suit coats.

The bassoonist Philip Langdale declined the Melbourne Exhibition Commission's offer of a steamship ticket to return to England, and instead stayed in Melbourne working as a professional musician. He played bassoon solos in Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide, and even New Zealand that were commended in reviews for their wit and musical facility. Then as now, the sound of the bassoon is associated with musical humor, even though it is very capable of producing many other profound and beautiful emotions.

But as time passed the Australian audience's acclaim was not enough to meet a musician's financial challenges. By 1894 Langdale was evidently struggling to keep afloat in show business and hinting the he would soon leave for Britain.

|

| Melbourne Table Talk 23 March 1894 |

He had certainly no reason to complain of the warmth of the greeting offered to him when he first appeared upon the platform, nor of the applause that followed his first solo, the "Carnival de Venice." And of the floral tributes offered to him nothing could have been more appropriate than the one woven in the form of a bassoon. The warmth of feeling shown him should be a guarantee to Mr. Langdale that he bears with him the best wishes of his friends and admirers.

But the programme was inordinately long, and was not, on the whole as readily carried out as usual. Apart from the performance by Mr. Langdale, who was naturally the central figure of the evening...

* * *

Langdale managed another year in Australia

before finally making his farewell concert in 1895.

A Melbourne wag wrote an amusing tongue-in-cheek tribute

that says a lot about Langdale and the friendships he made in Australia.

before finally making his farewell concert in 1895.

A Melbourne wag wrote an amusing tongue-in-cheek tribute

that says a lot about Langdale and the friendships he made in Australia.

|

| Melbourne Punch 11 July 1895 |

Mr. Phil Langdale, the eminent bassoon player, who is leaving the colony for England almost immediately, is doing so in consequence of the small demand for bassoon playing in this country. He attributes this lack of interest in the instrument to the political management of the colony. It would be worth while for him to clearly explain what sort of political administration ought to prevail in order to make bassoon playing popular and profitable.

What is there that is anti-bassoonical in our present politics? Wagner, if we remember rightly, called the bassoon the "clown of the orchestra," on account of its appropriateness for producing comic effects. There are so many clowns in politics that we should have expected them to take a fraternal interest in the instrument, if they had any inclination to interested in any instrument of music whatever.

We are, however, really sorry Phil Langdale is going, and hope that the state of politics, of which he complains will bas-soon altered.

* * *

This photo detective has tried to connect an unmarked portrait of a musician with a name that has no likeness, but regrettably it is not conclusive proof of identification. However, circumstantial evidence sometimes is sufficient too. So I'm convinced that a musician like Phil Langdale, whose talent on the bassoon was so frequently recognized during his years in Australia and whose wit and charm had endeared him to many friends, would very likely invest in a handsome photograph like this as a gift for his admirers. It the sort of thing one does when taking leave of a place and setting out on a long voyage to a distant land.

* * *

CODA

CODA

The following year, December 1896, Phil Langdale was on stage in London as a bassoon soloist with the Inns of Court Orchestral Society. His name appears much less frequently than when he was with the Coldstream Guards Band, probably because he was working in theater orchestras and seaside pier bands. In around 1900 he begins touring England with the "London Wind Quintette", an early instance of a professional wind chamber group. During the war years his novelty bassoon solos were occasionally worthy of note in newspaper reviews. The last mention of his name was in 1921 as principal bassoon of the Tonbridge Orchestral Society.

I've left out his family history mainly because it was never mentioned in the Australian newspapers and is not pertinent to my case. However I have documented his name in the UK census and other records and know that Phil Langdale, born in 1855, married Selina Campbell, age 19, in 1885. Whether she accompanied him to Australia, I do not known. They had two daughters, Nina, born in 1887 and Phyllis, born in 1903.

Philip Langdale, bassoonist, died on 22 October 1929 at age 74.

Curiously his name appeared

in the 1933 U.S. official catalogue of copyright entries

for a bassoon solo with pf. acc. (pianoforte accompaniment)

It was entitled

We won't go home till morning;

by Phil Langdale;

©Feb. 7, 1933 by Hawkes & son (London) ltd.

in the 1933 U.S. official catalogue of copyright entries

for a bassoon solo with pf. acc. (pianoforte accompaniment)

It was entitled

We won't go home till morning;

by Phil Langdale;

©Feb. 7, 1933 by Hawkes & son (London) ltd.

|

| 1933 United States Catalogue of Copyright Entries |

As a special musical homage

for his story

let's listen to a rendition

of one of Phil Langdale's favorite bassoon variations.

This video comes from a March 25, 2012 concert

at Edinborough Park, in Edina, Minnesota

featuring Alex Legeros on bassoon

with the Edina Sousa Band, playing "Lucy Long."

for his story

let's listen to a rendition

of one of Phil Langdale's favorite bassoon variations.

This video comes from a March 25, 2012 concert

at Edinborough Park, in Edina, Minnesota

featuring Alex Legeros on bassoon

with the Edina Sousa Band, playing "Lucy Long."

***

***

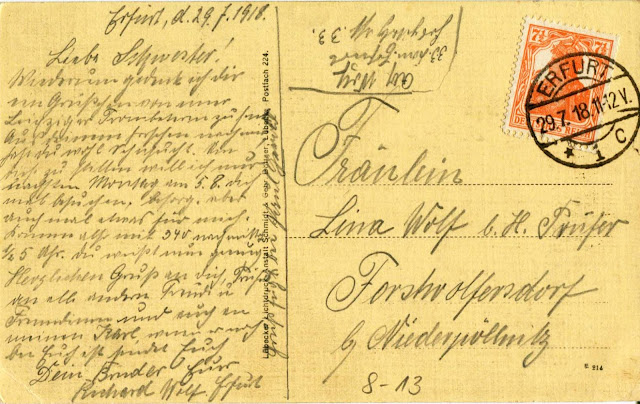

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where the batter is up and the basses are loaded.

where the batter is up and the basses are loaded.