You know that moment

when you can't remember a word?

When you can't think what to say

because your mind is stuck

in a mire of dark thoughts?

when you can't remember a word?

When you can't think what to say

because your mind is stuck

in a mire of dark thoughts?

Then suddenly your head explodes

with a whirlwind of emotions

chasing you like a swarm of angry hornets.

You can't take it any longer!

You just want to escape!

with a whirlwind of emotions

chasing you like a swarm of angry hornets.

You can't take it any longer!

You just want to escape!

Life can feel that way in stressful times.

„Die Glocke“ von Schiller

~

The Bell by Schiller

~

The Bell by Schiller

Einen Blick nach den Grabe Seiner Habe

Sendet noch der Mensch zurück.

=

A look at the grave of his belongings

Still sends a man back.

{ 2. ist jetzt = is now }

Fest gemauert in der Erden

Steht die Form, aus Lehm gebrannt.

=

Firmly walled in the earth

Is the shape, burned from clay

Steht die Form, aus Lehm gebrannt.

=

Firmly walled in the earth

Is the shape, burned from clay

{ 3. Karten = cards }

Von der Stirne heiss

Rinnen muß der Schweiss.

=

From the forehead hot

The sweat must run.

Rinnen muß der Schweiss.

=

From the forehead hot

The sweat must run.

{ 4. zu Schicken = to send }

O! dass sie ewig grünen bliebe,

Die schöne Zeit der jungen Liebe!

=

O! that she would stay green forever,

The beautiful time of young love!

Die schöne Zeit der jungen Liebe!

=

O! that she would stay green forever,

The beautiful time of young love!

{ 5. Als lumpen = As rags }

{ ja! ja! = yes! yes! }

Der Mann muss hinaus

Ins feindliche Leben,

=

The man must go out

Into hostile life,

Ins feindliche Leben,

=

The man must go out

Into hostile life,

{ 6. Doch hole ich mein Versprechen

gefallen sind belästige Dich wurt 8 karten }

=

{ But I get my promise

8 cards are bothering you }

gefallen sind belästige Dich wurt 8 karten }

=

{ But I get my promise

8 cards are bothering you }

Nun kann der Guß beginnen !

=

Now the casting can begin!

=

Now the casting can begin!

{ 7. für mich aber ist es ein sehr

auge___(?) Belästigen, darum erlaube

ich mir noch auf der 8ten }

=

{ but for me it is a very

eyes --- bother, therefore allow

I'm still on the 8th }

{ für mich leider nicht! = unfortunately not for me! }

Wehe, wenn sie losgelassen.

=

Woe, when it is released.

=

Woe, when it is released.

{ 8. mein herzliche Grüsse zu senden. }

=

{ to send my warm regards. }

=

{ to send my warm regards. }

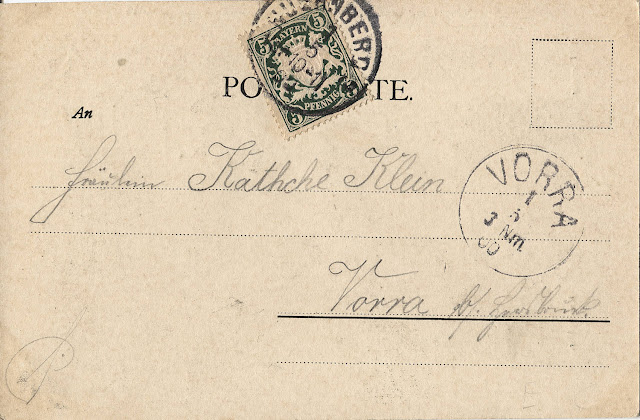

This set of seven Austrian postcards depicts an eccentric gentleman reflecting on several short lines taken from the German poet Friedrich Schiller's poem "Das Lied von der Glocke"–"The Song of the Bell". All the cards were posted on the same day, 30 March 1903, to Wohlgeborne Frau Anna Ritschl. The postmark was stamped somewhere in the Austrian-Hungarian postal service to judge from the 5 heller Austrian stamp, but the city name is obscured. The "Wellborn" Mrs. Anna Ritschl resided in Serben, Josefie 172, which I think is a place name followed by a street address. But I've been unable to find any place names in Austria or central Europe that match my interpretation of the spelling or any other alternate letter combinations. The word Serben in German means Serbs, but the nation of Serbia is spelled Serbien so I don't think that has any connection. Considering that Austrian/German post card publishers identified the Postkarte media in 17 languages, many of which were common to parts of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, it's a wonder that mail was delivered with such simple addresses and in such flashy cursive handwriting.

The writer numbered the cards in a sequence as a joke to Frau Ritschl, who was possibly his wife. Unfortunately I am missing the first card and maybe others. On the address side there is a publisher's mark, H. S. W. Serie 6, with numbers for each card design, and the writer's No. 2 is printed as Serie No. 10. So there were at least 10 different cards in the publisher's original set, though it is odd that No. 10-(2) quotes the opening lines of this well-known poem.

Here is "Die Glocke" postcard No. 1 which I happened to find this morning on a German eBay dealer's listings. It has a postmark from Berlin in 1904. I hope to get this one and maybe one day No. 9 and 10 to complete the series

It's a charming set that uses multiple cards to express a personal greeting, characteristic of a social fad that was very popular during the first decade of the postcard's introduction to the European postal service. In each image just beneath the man's right arm is a name and date: Triebel—Wien XVIII 1902 printed on the card. I think this is the name of the photographer as in 1900 there was a studio in Wien with the name Triebel. But it could be the name of the comic character actor pictured. Clearly there is something funny about him that is lost in translation.

Speaking of translation, the English translations of the German words in the poem and in the message are my own using Google's translate app to get a literal meaning. I welcome any improvements or corrections.

_ _ _

The poem's full title is "Das Lied von der Glocke" – "The Song of the Bell". It was written in 1798 by Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) and is considered one of the finest poems in German literature. Despite its length at 430 lines, it became a standard work for study in German and Austrian schools, and during the 19th century many of Schiller's lines would have been easily recognized by most German speakers. Clearly as depicted on these postcards from 1903 it was still a beloved poem that could convey the joy of life just using snippets of lines.

Though I knew of Friedrich Schiller, a contemporary of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), I did not know of this poem or how celebrated it was in German culture until I bought these seven postcards. His poem uses an extended metaphor of a great bell to illustrate human life from birth through death. Schiller, who grew up living next to a bell foundry, was very familiar with how a bell was made and in his poem he describes much of the metal craft used in casting a bronze church bell while interweaving an idea of how the peal of the bell will be associated with baptisms, weddings, alarms for storms, fires, or even war, and then ultimately sound the death knell for a funeral. The words and symbolism connect to German values of hard work, craftsmanship, and respect for rural traditions and people. The poem has a motto in Latin that reads "Vivos voco. Mortuos plango. Fulgura frango", which translates roughly as "I call the living, I mourn the dead, I repel lightning." In earlier times the tremendous clangor of a bell was thought to drive away thunderstorms.

As it was published in 1798, Schiller was partly responding to the horrific excesses of the French revolution (1789–1799) and warning how war might again break the accord between the people of Europe. Which is exactly what happened when Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in 1800. It was also a time when the many German states and principalities were not yet united into one nation. In his poem Schiller ends with the sound of the bell signifying Peace, and I think that is what made the lines so powerful and memorable in the years following Schiller.

Very soon after it was published "The Song of the Bell" was translated into other languages, but each time the rhythm and rhyme of Schiller's German words were adapted to suit the patterns of the new language. In comparing English translations I found a LOT of variation. Some editions may express Schiller's intent but frequently his poem is distorted by the translator's penchant for English poetic styles. Here are three versions of the last lines of "Das Lied von der Glocke" where the bell is first raised from the ground to show what I mean.

To illustrate why Schiller found the bell such an inspiring theme, here is a video taken in 2012 at the Grassmayr Bellfoundry in Innsbruck, Austria. This is the first test ringing of a gigantic bell commissioned for the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Mount Tabor in Israel. I think the bell is suspended over the pit where is was cast. It weighs 15,684 kg / 17.28 US tons, not counting its yoke and clapper. It's principal tone is a d/0.

* * *

* * *

In Schiller's pre-industrial time a great bell was one of the largest objects that could be produced by 18th century metallurgy, which was then more of an art than a science or technology. An artillery cannon was the next largest thing made from cast metal. (Excepting bronze statues which are not made for reasons of utility.) Both bells and cannon were difficult to manufacture, involving dangerous risk to the makers if done improperly. And in this era both made the loudest man-made noises then known to man—with one important difference. A bell tolls for a peaceful purpose, while a cannon roars for destructive violence. The percussive sound of each can physically rattle the heart and take ones breath away, which is something Schiller surely experienced and recognized how the bell could be used as a powerful metaphor.

This week as I tried to understand how the short excerpted lines of Schiller's poem related to the funny old fellow on the postcards, I was struck by the difference between literature and music. To fully appreciate the humor of the postcards and the wisdom of Schiller demands a thorough understanding of the German language. In literature, language is always a barrier to understanding.

But to play German music, or for that matter music from any national region, a person requires nothing more than a knowledge of music notation. Like mathematics, music is a universal language. And the enjoyment of music needs only a love for rhythm and melody. It is an art form that transcends national borders and connects humanity with a fundamental emotional bond.

There are plenty of great poets in the English language, so I may be excused for not knowing about this famous German poem. But I do know one of Schiller's other works very well, which I believe many people know too without knowing the name of the poet. Do you recognize it?

Bom, Bom, Bom, Bom,

Bom, Bom, Bom, Bom,

Bom, Bom, Bom, Bom,

Bommmmm, - Bi, Bom, — [repeat]

Bom, Bom, Bom, Bom,

Bom, Bom, Bom, Bom,

Bommmmm, - Bi, Bom, — [repeat]

It is, of course, "Ode to Joy" or "An die Freude", written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and used by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1824 for the final choral movement of his immortal Symphony No. 9. Beethoven's march tune is the most hum-able melody in the symphony (which I bet many readers are hearing in their head right now!) that enshrines Schiller's stirring words within the most glorious orchestral music every composed. I don't believe it is ever sung in performance in any language other than the original German. When non-German choruses sing it they must learn the words meaning from reading translations but they still sing Schiller's original words as interpreted by Beethoven's music.

Schiller died in 1805 and I don't think he ever met Beethoven, though I expect Ludwig was very familiar with all of Schiller's poems. But fate and Beethoven's supreme musical artistry led him to choose "An die Freude" as a subject for his final symphony now recognized around the world. In 1972 it was adapted by the European Union as the Anthem of the Europe. We can only imagine what Friedrich and Ludwig would think of the unification of the European people, and the use of their very abridged music and poem.

Would they shake their heads in dismay

that something was lost in translation?

that something was lost in translation?

* * *

* * *

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday.

Shhh! Quiet! This is a library weekend.

Shhh! Quiet! This is a library weekend.