The fiddler bows low in supplication.

His clothes are ragged and his feet are bare.

"A few coins, please, for my music," he pleads.

His clothes are ragged and his feet are bare.

"A few coins, please, for my music," he pleads.

The caption in Hungarian reads:

Ide azzal a borra:

Szomjazik a Kátsa,

Csiklandozza torkát még

Töpörtus pogάcsa.

~

Szomjazik a Kátsa,

Csiklandozza torkát még

Töpörtus pogάcsa.

~

Here with that wine:

Kátsa is thirsty,

Tickle our throat with some more

Puff pastry.

This colorful illustration of a musician appears on a Hungarian postcard dated 1903 June 20. The dating convention in Hungary at that time was to use a year/day/month pattern and leave off the first numeral 1 from the year. It was sent from Dunaszerdahely, which is now called Dunajská Streda in southern Slovakia. The town was first mentioned in records from 1256. The word Szerdahely means "Wednesday (market)place" in Hungarian and today the town is still predominantly inhabited by ethnic Hungarian people. Kátsa is thirsty,

Tickle our throat with some more

Puff pastry.

The fiddler's postcard caught my attention mainly for its vivid colors which despite the passage of 120 years are still bright. The musician's shabby appearance is not unlike that of street buskers seen in cities around the world. In fact he looks better dressed than some of the street musicians found here in my hometown in western North Carolina. What sold me on this whimsical card was the discovery that there were more in the same series.

On this card the fiddler clasps his hands in prayer while gazing up to the sky. If his first plea did not work then perhaps an appeal to a higher authority will. His tattered blue jacket and red trousers are similar to a European military bandsman's uniform. In the lower left corner are initials: WK.C.Bp. which I interpret as the mark of the publisher and not an artist. The printing method is lithography which probably accounts for it better quality ink. It needed only a tiny bit of digital correction of some faded contrast. The card has no printed verse and was never mailed.

Jól izlet a májas hurka,

Meg a malacpecsenye,

Ilyen ếtel a czigánynak

Minél többször kellene.

Koplal sokat a szegény

Kóczos, fekete legény.

~

The liverwurst looks good,

And the pork roast,

Such food for gypsies

As often as possible.

The poor man fasts a lot

A disheveled black fellow.

Meg a malacpecsenye,

Ilyen ếtel a czigánynak

Minél többször kellene.

Koplal sokat a szegény

Kóczos, fekete legény.

~

The liverwurst looks good,

And the pork roast,

Such food for gypsies

As often as possible.

The poor man fasts a lot

A disheveled black fellow.

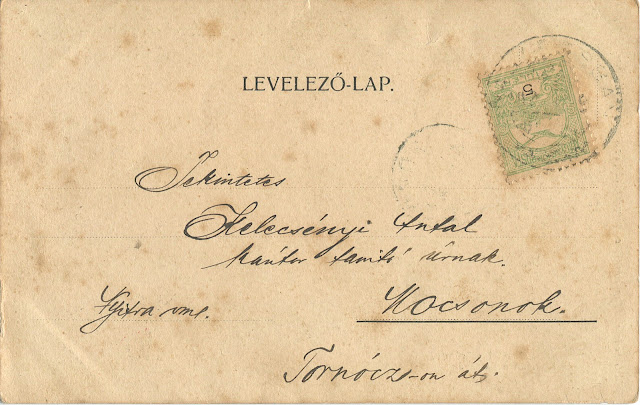

Now the fiddler glances covetously at some tempting food according to the verse. The sender of this postcard adds a line: Tanifókkal eqzyűl ~ He met with Tanifos, which probably was a funny remark that made sense only to the recipient. Like the first card this postcard was also sent from Dunaszerdahely on 3 June or July 1902. In this era Dunaszerdahely was in Hungary, a part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, but Hungary was still a separate kingdom and had its own postal service. Notice that someone, maybe the postman, has struck through the alternate foreign names of this postal media leaving only the Hungarian name: Levelező-Lap, which translates literally as Correspondence-Sheet.

Here the fiddler holds out his hat to ask for coins, a universal gesture recognized since ancient times. The unknown artist has kept a consistent style and given the man a variety of charming expressions. This card shares the same style printed back as the others but was never posted.

My last card of the fiddler has him begging down on bended knee with his dark eyes turned to the viewer in an imploring gaze. I feel certain there is a 6th card where he is playing his violin as this was the typical number printed for postcard series, but I will have to remain patient and watchful until I find it.

The artist's depiction of this vagabond musician fits with artwork I featured in my story from August 2022, The Romantic Violin. Like those passionate violinists, this fiddler is a fanciful romantic creature too, but unlike them he is also an example of a racial trope. European people in 1902 would have instantly labeled him as a Zigeuner, a Gypsy, or more properly a Romani. Though he is rendered in a gentle way as a poor tramp he embodies an ethnic cliche that appears in many other postcards from this same period.

The Romani people are said to have originated in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan. After the invasion by Islamic forces in AD 1000-1040 the Romani migrated into the Byzantine empire and then central Asia. They appeared in Europe first in the Balkans in the 13th century; then Bohemia in the 14th; followed by Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Portugal in the 15th; and by the 16th century they were in Russia, Denmark, Scotland and Sweden. They were a nomadic people who seemed never able to settle in one place, mainly because they were abused and persecuted everywhere they went.

The Romani were often portrayed disparagingly in Western culture for their stubborn independence, criminal pursuits, and knowledge of arcane arts like mysticism and fortune telling. Yet many artists, writers, and composers were attracted to their culture and created Romani, Gypsy characters to add an exotic or provocative allure to their work. Perhaps the best-known musical character is Carmen, the beautiful Spanish Gitano (Romani) woman in Georges Bizet's popular opera of the same name, adapted from Carmen, an 1845 novella by the French writer Prosper Mérimée.

But Romani culture was also recognized for its music, especially on the violin. Many great composers like Brahms and Liszt were influenced by Romani rhythmic dance forms and melodies played in a characteristic minor mode. Thus the Gypsy fiddler became a popular figure for European artists.

* * *

In this postcard another artist renders a colorful bearded fiddler seated on a small keg. He is dressed very like the other fiddler with a short blue jacket and soft hat and his violin and bow under his arm. Curiously he holds a postcard-sized painting of himself as if offering it for sale. Under this small printed watercolor is a name: Docili Mocili just beneath a tiny silhouette of a black dog or pony. The caricature also has two lines of verse.

Tzigánynyal álmodni szöröntse, de legkivált a Kártyával.

~

Don't be afraid to dream with Tzigány, but especially with the Card.

~

Don't be afraid to dream with Tzigány, but especially with the Card.

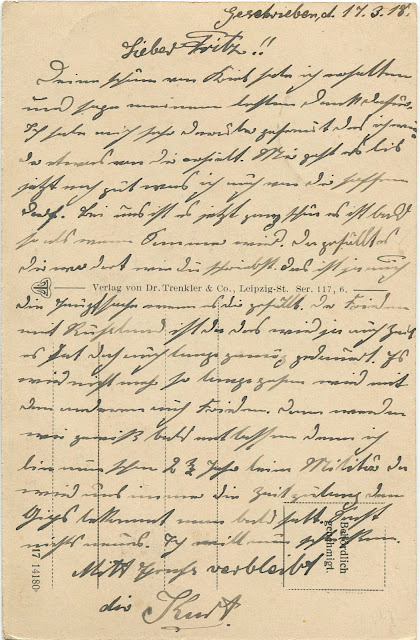

This is Google's translation but Hungarian is a very difficult language so I'm not satisfied that this is the best interpretation. I tried to translate the lengthy message but despite the relatively clear handwriting, there are far too many letter choices to get a good translation. I have a feeling that it just says, "We did/did not receive your letter. Everyone is well/not well. Write more soon." The Hungarian postmark is too faded to read, but the sender wrote a date of 1902.VIII. 9.

* * *

This quaint image was printed in München (Munich), Bavaria and sent from there to someone in Württemberg on 3 December 1899.

To demonstrate the fantastic quality of Romani music

here is a short video of “Caliu” aka Ghoerghe Anghel,

a violinist with the Romani group Taraf de Haidouks,

playing solo for his family in his back garden.

here is a short video of “Caliu” aka Ghoerghe Anghel,

a violinist with the Romani group Taraf de Haidouks,

playing solo for his family in his back garden.

* * *

From the beginning of the postcard era in the 1890s novelty cards of Romani individuals like a happy busking village fiddler were not uncommon, but I've discovered that during World War One a different kind of picture postcard of Romani people was produced. These were photos usually printed in a grim sepia tone and often captioned: Zigeunerleben ~ Gypsy life like this card. It shows a Romani mother with five small children standing outside their thatched roof cottage.

This postcard was sent via German military post on 18 January 1918. The publisher's name is from Berlin and this was likely printed especially for soldiers either leaving or returning from the front. The location of the Romani family is unknown but since Germany's Eastern Front with Russia was much longer and included Romania and Serbian forces too, this family was likely living in eastern Europe.

* * *

This next postcard shows another Romani family standing outside their home alongside some German soldiers. The caption reads: Zigeuner und Feldgraue vor einer Zigeunerhütte ~ Gypsies and military men in front of a gypsy hut. The soldiers have no weapons and the picture seems almost pastoral, but the shoddy condition of the house implies a level of grim poverty that would fit the German idea of the Romani people. Were the soldiers seen as liberators or benevolent saviors?

In February 1917 the Imperial Russian monarchy was overthrown in the first Bolshevik revolutions. After that the war with Russian ended, but the war with Romania continued. Though this front was shorter it involved a huge number of combat units and several important battles were fought in the region of Moldova where the Romanian army was able to halt the advance of the German and Austro-Hungarian armies. This isolated conflict of WW1 was not resolved until the Treaty of Bucharest in May 1918.

This postcard was sent in a letter by a German soldier on 17 March 1918. I'm unable to translate the content of the message, but it seems very likely that it was sent from the Romanian Front.

My last postcard is a photo of a rural encampment of Romani people. They sit on the ground under simple tents and one man holds a donkey laden with packs and three small children. The caption, in both German and Hungarian, reads: Wanderzigeuner – Vándorczigányok ~ Wandering gypsies. This card was never posted but the back is imprinted with the Hungarian word for postcard, Levelező-Lap, and it has a caption identifying the publisher: Nr. 436 Kunstanstalt Jos. Drotleff, Hermannstadt. Nachdruck verboten ~ Reprinting prohibited. Hermannstadt was the German name of Sibiu, a medieval town in central Romania, situated in the region of Transylvania, then part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

Throughout the war years millions of German, Austrian and Hungarian people shared postcards with each other. Though the colorful prewar cards were often printed in dull monotones to follow government rules on restricted materials, the demand for unusual and novelty themed cards increased with so many soldiers serving on multiple fronts. I'm not certain how it was ordered but many of the wartime postcards were obviously devised as propaganda. See my recent story, Looking Through the Lens of History, where I compare two versions of the same Ukrainian peasant couple, one sepia tone and the other in color.

One of the common themes on these wartime cards is images of exotic people–foreign folk marked by their unusual headdress and sometimes dark swarthy complexions. I think the idea was to diminish the enemy people, making them appear weak, unintelligent, even ridiculous. It was a method used throughout history and around the world to create The Others, that is, People Not Like Us. The Romani people were included in this larger collective group along with Russians, Africans, and other ethnic and national minorities. Tragically the Romani, who had already experienced centuries of wicked pogroms, would soon suffer the worst injustice with the murder of hundreds of thousands of Romani, perhaps as many as 1.5 million, during Hitler's genocidal extermination of Jews and other so-called "undesirable" peoples.

I don't make any direct connection between my small collection of early 20th century Romani postcards and the evil of the Holocaust which happened a few decades later. However these images do convey a public acceptance of European bigotry and prejudice in much the same way that early America postcards depicted African-Americans, Native Americans, Hawaiians, Mexicans, Chinese, and Japanese in similar degrading racial tones and tropes. Our Western culture once included many racist elements that in olden times were considered inoffensive but which today we would deem totally unacceptable. Yet if we fail to remember this difficult history of bigoty our society may regress and repeat it.

* * *

I will finish with two videos of the Romanian band, Taraf de Haidouks.

These are excerpts from a 1993 film called Latcho Drom (Safe Journey)

which tells a story of the history of Romani musicians

from Rajastan (India), Egypt, Turkey,

Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, France and Spain.

These are excerpts from a 1993 film called Latcho Drom (Safe Journey)

which tells a story of the history of Romani musicians

from Rajastan (India), Egypt, Turkey,

Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, France and Spain.

The two simple scenes vividly connect

the postcards of the poor Romani fiddler

to the images of Romani village life.

the postcards of the poor Romani fiddler

to the images of Romani village life.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where the horse always

comes before the cart.

where the horse always

comes before the cart.

zxc

.jpg)