The building seems to gleam

like a small cloud floating above the city.

The distant shape could be a stately palace,

a venerable basilica, or a grand museum.

But from its location in this illustration

there's a suggestion that this place

should be the focus of the viewer's attention.

like a small cloud floating above the city.

The distant shape could be a stately palace,

a venerable basilica, or a grand museum.

But from its location in this illustration

there's a suggestion that this place

should be the focus of the viewer's attention.

In a way it is all those things, and more.

This was, and still is, a true temple of music.

It is the Festspielhaus of Bayreuth.

The living shrine to the music of Richard Wagner.

It is the Festspielhaus of Bayreuth.

The living shrine to the music of Richard Wagner.

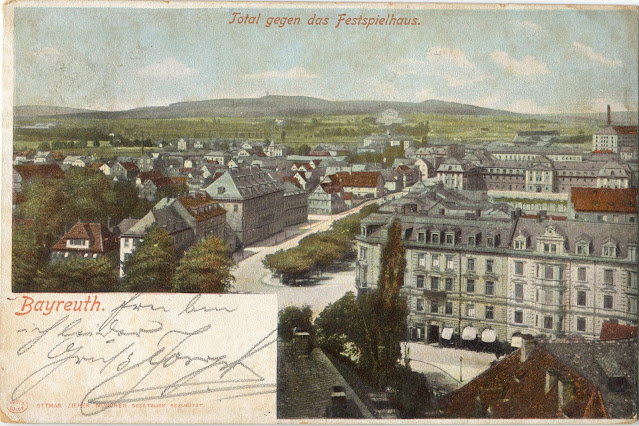

The Festspielhaus is seen faintly in the back center of this colorized bird's-eye-view of the city of Bayreuth which is situated in Bavaria, about 48 miles northeast of Nürnberg. The postcard was printed by Ottmar Zieher of München and, based on my analysis of Google's modern maps, was likely made from a photo taken from atop the 16th century tower at the famous Schlosskirche in Bayreuth.

The postcard was sent from Bayreuth on 15 July 1902 at 3-4 PM and arrived at Wunsiedel, a town 25 miles east, a few hours later at 7-8 PM. It was probably no more than a quick message of safe arrival written on a tourist postcard but it serves to demonstrate a bit of German culture that still retains the same qualities 120 years later.

The Festspielhaus of Bayreuth was built by the composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) specifically for the performances of his operas. Work on the theater's foundation began in May 1872 and the theater opened in August 1876 with the premiere of Wagner's complete four-opera cycle of Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung). The four operas, in order, are:

- Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold)

- Die Walküre (The Valkyrie)

- Siegfried

- Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods)

The Ring Cycle, as it is commonly called, is considered the most challenging production for any opera company to undertake as it requires four separate performances which together total about 15 hours of playing time. Götterdämmerung, the last opera, is typically 5 hours long. In recent times since WW II, with the exception of 2020's pandemic, the Bayreuth Festspiele has presented every summer, either a full production of the Ring Cycle, or a mix of Wagner's other famous works: Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and Parsifal, which together are called the "Bayreuth Canon". Only the operas of Wagner are programed and they are usually repeated a few times during the festival, which now lasts from from the end of July to the beginning of September.

Richard Wagner is arguably one of the most influential composers of the 19th century, whose works inspired many composers and theater producers, too. Though the majority of his works were written for the stage, as opposed for the concert hall, Wagner's music introduced many new ideas of melodic structure, chromatic harmony, and dramatic use of music that were revolutionary in his time. His musical talent led many people to consider him a genius, while others were shocked, and even repulsed, by his overwrought music dramas. Wagner was also a prolific writer and his ideas on music, drama, philosophy, and politics were often very controversial and at odds with established norms. In his personal life he earned a reputation for tempestuous love affairs, shameful financial schemes, and an ego without limit. Yet it was Wagner's boundless imagination as revealed in his fantastic operas that attracted the adoration of millions of people.

Like with all of his other operas, Richard Wagner wrote his own libretto for the Ring Cycle as well as the music. He wanted the story to be an immersive performance that integrated music and staging to support the drama, what he first conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk or a total work of art. Later it became known as a Musikdrama or music drama and was intended by Wagner to be an artform that was different from traditional operas of the 18th and early 19th centuries. His first Musikdrama, Das Rheingold, opened in September 1869 at the Bayerische Staatsoper ~ Bavarian State Opera in Munich, followed by Die Walküre in June 1870. The last two works, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung were first performed in 1876 at his new theater in Bayreuth.

This portrait of Richard Wagner comes from a postcard series produced by the Austrian artist, Herman Torggler (1878-1939). I featured another copy of the postcard in my December 2020 story, Hermann Torggler's Great Composers - part 2 which dates from 1912. This one has a postmark of 8 February 1913 and was sent from Ludwigsburg, a city north of Stuttgart and about 150 miles (242 km) from Bayreuth.

Wagner began thinking of a personal theater when his early operas were not received with the respect he felt they deserved. The way opera houses followed certain conventions, like always including one act with ballet, upset him and he desired more artistic control free of obstructive government censors and uncooperative theater directors.

He was attracted to the city of Bayreuth partly because it was outside the legal limits of the music publishers who owned the rights to his music. He preferred a royalty-free zone, so-to-speak, though Bayreuth had plenty of royal history. In the town there was an old theater called the Margravial Opera House which Wagner thought might be large enough for his operas. It had also been closed for a hundred years.

|

| Margravial Opera House, Bayreuth, Germany stage view Source: Wikimedia |

The Margravial was a theatre built in 1744–1748 for Margrave Frederick of Brandenburg-Bayreuth and his wife Princess Wilhelmine of Prussia. It was richly decorated in a high baroque style with gilded ornate carvings and classical paintings. Though the stage was very deep, 27 meters (89 ft), the orchestra platform was visible and not hidden in a pit. It was also too small for the size orchestra Wagner wished to use. The stage proscenium was also too narrow for the special effects that Wagner envisioned and unsuitable for a large chorus or cast. It also only seated 500 people.

|

| Margravial Opera House, Bayreuth, Germany court loge view Source: Wikimedia |

The margrave and his wife were generous patrons of the arts. In 1737 Princess Wilhelmine, who was the eldest sister of the Prussian king Frederick the Great, a celebrated flutist in his own right beside being a king, established her own theatre company in Bayreuth. When their new opera house opened in 1748 the princess put on operas and Singspiele that she composed and even worked as an actor and director. The theater was closed to performance upon her death in 1758 and by the 1860s had been left neglected but preserved.

When he first saw it Wagner probably instantly recognized that the Margravial Opera was inappropriate for the gigantic operas he imagined. Nonetheless he liked Bayreuth and persuaded the city's officers to approve his project for a bigger modern theater. It would require a lot of money, but he felt he could finance some of it through concerts as he was also a conductor. His earlier operas had attracted enough popular attention that he could organize Wagner Societies around Germany to raise music for the theater. He even appealed to the German government for funds. It wasn't enough. Yet Wagner knew of one man who had very deep pockets indeed. He would ask Ludwig.

This postcard has a viewpoint almost identical to my first colorized illustration, but this is an engraving that, I think, must be copied from the same photo taken in Bayreuth's church tower. The caption offers Greetings from Bayreuth and Blick zum Wagnertheater ~ View of Wagner theater. The Festspielhaus is faintly visible below the mountains. This is one of the oldest picture postcards in my collection as the postmark date is 14 September 1898 from Bindlach, a suburb of Bayreuth.

The city of Bayreuth gave Wagner some undeveloped land on a hillside beyond the city center to build his theater. They probably expected a famous composer like Wagner would bring in a lot of tourists. Wagner also acquired property nearby to build a villa for his wife and their family. He gave it the name Wahnfried and it is now the site of the Richard Wagner Museum. His wife Cosima Wagner (1837–1930) was the daughter of Hungarian composer and pianist Franz Liszt and the Franco-German romantic author Marie d'Agoult. She was Wagner's second wife and after his death in 1883 she took charge of managing the festival and safeguarding her husband's legacy.

Wagner "borrowed" several designs from conceptual plans for a theater in Munich that were created in 1864-66 by the great German architect, Gottfried Semper (1803-1879). Semper designed Dresden's opulent opera house which I featured in my story from November 2013, Feuer in der Oper! Fire at the Opera House!. Unlike the seating in most theaters of Wagner's time, here in Bayreuth all the patrons sit on a single steeply angled floor without multiple tiers of box seats and galleries.

This postcard likely dates from 1911-12 as, even though the postmark is obscured, the 5 pfennig stamp has the years 1886 – 1911 in commemoration of Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria (1821–1912). Luitpold was named regent in 1886 after his nephew King Ludwig II (1845– 1886) was declared mentally incompetent. It was King Ludwig, known as "the Mad King" of Bavaria, who was responsible for building several grandiose castles and extravagant palaces in Bavaria like Neuschwanstein Castle, which inspired Walt Disney's fantasy "castles". Ludwig was also a generous patron of the arts, and had already been a great benefactor to Richard Wagner. Though he was reluctant to help again, when Wagner asked for support he agreed to finance Wagner's dream of building an opera theater in Bayreuth.

Three days after Luitpold assumed the regency in June 1886, Ludwig took his own life, and was officially succeeded as King of Bavaria by his younger brother Otto (1848–1916). However since 1873 Otto had been kept in medical confinement after several episodes of severe mental illness and remained isolated for the remainder of his life. His biography is just one of several tragic stories found in the history of Bavaria's monarchy. Stories with enough drama to inspire a composer of grand operas.

A great many streets of Bayreuth are named after either Wagner's opera titles, or the characters, or celebrated musicians and conductors connected with his music. From Bayreuth's train station to the Festspielhaus is an almost straight line, little more than a kilometer, to the theater's park along Siegfried-Wagner-Allee, named after Wagner's son. In the short summer season the Festival route can get quite congested though before the age of automobiles it was carriage traffic that caused delays. This postcard was sent from Bayreuth on 24 July 1909 and shows how the Festspielhaus is situated for impressive effect.

The Festspielhaus was built with timber-frame construction and a red and white brick facade with modest ornaments. It seats 1,925 and the structure, including stage and fly-space, has a volume of 10,000 cubic meters. The theater's exterior was recently repaired in 2015. This postcard has a postmark of 2 December 1907 and shows the entrance where patron would alight from their carriages.

The length of Wagner's music dramas required a lot of stamina from an audience but the intervals (or intermissions in American) between acts were generous and offered a chance for refreshments. During these breaks it became a Bayreuth tradition to announce the resumption of the opera with a fanfare played by the orchestra's brass section. Each call is a short excerpt from the opera of the day.

This postcard was postmarked 18 August 1909 from Bayreuth and was likely purchased at the festival. It shows 12 members of the trumpet and trombone sections playing a fanfare. The music is printed in a cutout above them and comes from the third act of Götterdämmerung. Here is how it was performed in Bayreuth in August 2017 for Vincent Vargas who seems to have heard several of Wagner's operas that season.

The late 19th century brought significant changes to the instrumentation of an orchestra. For example there was no tuba in Mozart's or Beethoven's orchestras, and most trumpets and horns did not have valves until the 1850s. Generally in the Classical era wind instrumentalists came in pairs and operas rarely needed extra players. But Wagner wanted lots more sound, especially in the bass range. When he insisted that a bassoon should play a low A even though the instrument's lowest note, a B-flat, is a half-step higher, instrument makers devised a longer instrument just for his opera. Today's players make-do with a simple cylinder extension attached to the bassoon's bell that lets them reach that pitch.

Wagner also called for 8 horns in the Ring Cycle and requires that 4 horn players also double on a small tuba that is now called a Wagner Tuba because he specifically ordered that it to be invented, and in both F and in B-flat flavors, too. Similarly he added a bass trumpet and a contrabass trombone to his orchestra.

At the beginning of Das Rheingold there is a scene with a great forge, there are a lot of magic rings, swords and spears used in the Ring Cycle, so Wagner requests the percussion section use 18 anvils—nine small, six medium, and three large—all tuned to 3 octaves of F. In the finale he writes parts for six harps to help depict "Entry of the Gods into Valhalla". Typically a production of one of Wagner's music dramas has 90 musicians in the orchestra pit. And in Bayreuth Wagner designed this space for his orchestra with very specific features unlike other theaters.

The orchestra pit in most opera houses puts the musicians on a lowered flat floor in front of the proscenium which is still visible to the audience. But in Bayreuth's Festspielhaus Wagner wanted the orchestra to be hidden and not distract from the drama on stage. He also wanted to control the dynamics of the orchestra by building the pit on a steep slope with several levels descending downward beneath the stage. He then put brass and percussion at the bottom level and violins at the top with the conductor's podium another step higher. This arrangement balanced the acoustics so that the vocalists on stage were not overwhelmed by the orchestra's sound.

In this postcard dated 17 July 1906 the photographer is on one side of the Festspielhaus pit looking upward to the conductor, Richard's son Siegfried Wagner (1869–1930). Behind him is a curved wall that covers the strings and over the winds and brass another awning is attached to the stage floor. The result was that the audience could hear but not see the orchestra, and no one, other than the conductor, in the orchestra pit could see the action on stage. Though the sound was favorable for singers coordinating the timing of the music is a major challenge for a conductor.

As a young man Wagner's son Siegfried initially considered a career as an architect. But his father's legacy destined him to become a conductor and composer, too. In 1908, two years after this postcard's date, Siegfried took over as artistic director of the Bayreuth Festival after his mother retired from the position. In 1930 Siegfried died at age 61, just four months after his mother Cosima. His wife Winifred succeeded him in managing the festival.

Here is a short video produced by the Bayreuther Festspiel that shows what Wagner's theater looks and sounds like from the perspective of the pit. It should start at 3:57 which is when the orchestra plays the exciting "Ride of the Valkyries". The beginning is also interesting where one of the horn players explains how his part is played, however it is in German without English translation.

.jpg) |

| Jean de Reszke as Siegfried c. 1896 Source: Wikimedia |

In Siegfried, the third music drama of the Ring Cycle, Wagner wrote a solo for the horn, my instrument, which is arguably the most famous tune in all of his operas. It is called Siegfrieds Hornruf and it embodies the romantic and heroic ideals that Wagner wanted in his dramatic characters and music. The fanfare is supposedly played by Siegfried in a dark forest as he tries to attract a magic bird. Instead his horn call only awakens the dragon Fafner who Siegfried then slays with his sword. The actual solo is played by a hornist hidden behind the scenery on stage who follows the action of the singer. It's a very exciting tune that takes the horn into its top range. It's always included on auditions and every horn player learns it, though few ever get a chance to play it.

There are lots of videos on YouTube of someone playing Siegfried's horn call by itself but very few that show a view of how it appears on stage. This short excerpt of the famous Siegfried horn call is the best I could find, though it cuts off just when the dragon's tail appears. There are no details about the production but the horn call is played by Nobuaki Fukukawa, principal horn of the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Tokyo.

The Great War caused the Bayreuth Fest to suspend its summer season in 1915 and performances did not return until 1923. During the postwar era the festival resumed its status as a premier destination for lovers of Wagner's music dramas and even managed to continue productions after the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Doubtless this was due to the prominent support of one particular devotee of Wagner's music.

This photo shows the interior of the Festspielhaus with its open raked seating plan and simple stepped walls without traditional box seats. The stage has a painted backdrop of an Italianate courtyard but all the seats are empty which give the sepia-tone photo a grim forbidding quality.

In the 1930s the reputation of the Bayreuth festival suffered from its connection to Adolf Hitler. From the beginning of his political career Winifred Wagner developed a close personal friendship with him and became a strong supporter of the Nazi party. Before the Great War when Hitler was a young man with artistic ambitions he had lived in Vienna where he was introduced to the music dramas of Richard Wagner. After taking power in 1933 Hitler frequently attended the festival and was known to admire Wagner's music for its Germanic nationalism. After the war started the Nazi party took control of the festival and for a time subjected wounded soldiers to benefit performances of Wagner's operas with special lectures on Wagner's music and life. The festival was finally closed in 1943 and did not reopen until 1951. Sadly, late in the war the city of Bayreuth was targeted by Allied bombing which destroyed two-thirds of the city including part of Wagner's house, Wahnfried. Fortunately the theater withstood the attack unharmed.

This card was sent from Bayreuth on 20 July 1943 with an extra souvenir imprint of "Bayreuth the city of Richard Wagner" oddly mirroring the stamp of Adolf Hitler.

Producing any opera requires an army of workers but the Bayreuth Festival is exceptionally large. Since 1886 it has hired a huge orchestra of over 200 musicians (18 horns in this coming season) made up of the best musicians in Germany and abroad for its summer season. For all the operas there might be as many as 45 vocal soloists in the casts, and the chorus easily numbers over 130. Then there are countless people employed in handling the costumes, makeup, lighting, and sets, not to mention the auxiliary teams that manage tickets, concessions, security, catering, and general maintenance for the festival's theater and park. For this coming summer in 2024 there are 30 performances of eight operas, all by Richard Wagner. Tickets for most of the performances are now sold out.

Without question Richard Wagner was a singular musical genius. Unlike Niccolò Paganini or Wagner's father-in-law Franz Liszt, his fame was not earned as a virtuoso instrumentalist but only as a composer of musical dramas. And unlike Rossini, Verdi, Gounod, Meyerbeer and other opera composers of his generation, Wagner did not cater to popular tastes but wrote music dramas that pursued higher ideals than mere entertainment. Certainly Wagner the man had many flaws that made him controversial in his own time and which continue to provoke questions about his place in history today. But my interest in collecting postcards of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus was less about Wagner's music than about how it was this theater, built to Wagner's own plans, that made Bayreuth a shrine to his art and life's work. I can think of few composers or artists who have achieved this kind of lasting legacy for their works preserved in a single place.

Without the Festspielhaus Wagner's greatest music, the Ring Cycle and his last opera Parisfal would likely never have been produced. We should not forget that in the time before film and recorded music the only way to appreciate theater, opera, or music was to witness it live in person. His influence in music and opera theater might have disappeared after his death were it not for the hundreds of thousands of people who came to the Bayreuth festival to watch and listen to this great works. Even now, a century and a half later, Bayreuth remains a pilgrimage site for both devotees of Wagner's music and great performers who aspire to presenting his monumental music in the place he designed.

-

This last postcard dates from November 1975 and gives a better birds-eye-view (or helicopter view) of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus looking northeast. I suspect the residential area around the theater grounds was more forest and fields in Wagner's time. I imagine that during his theater's construction Wagner surely wandered over this beautiful landscape to gain inspiration for his dramas.

To finish here is the final scene in Götterdämmerung known as Brünnhilde's Immolation. It is from a Bayreuth production in 1976 directed by Patrice Chéreau with Gwyneth Jones as Brünnhilde, and Fritz Hübner as Hagen. The conductor was Pierre Boulez.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where sometimes stories

can go on and on

can go on and on

just like grand opera.