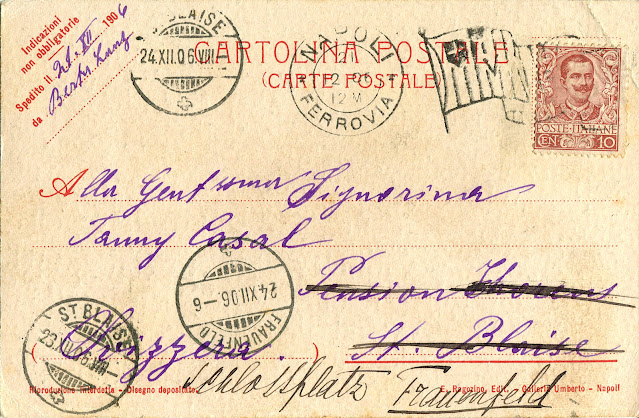

This is Bertha Noss.

When this photo was taken

Bertha was about age 11-12 years old.

She was the youngest of six children,

with two brothers and three sisters,

so to get any attention she learned to make a big noise.

Which Bertha did very well because,

besides the cymbals and bass drum,

she had a talent to play

many other musical instruments too.

Yet even though she looks very young in this photo

she was already a seasoned entertainer.

As was everyone else

in her Noss family band,

one of the hardest-working families in show business.

But before we get to Bertha, let's begin with introducing her family.

On the left, seated at a reed organ with her feet barely able to touch the foot pedals for the instrument's bellows, is Charlotte Noss, or Lottie. She played piano and bass in the family orchestra, alto horn in their band, and was a vocalist too. Next to her was Ferdinand Noss, or Ferd. He played violin (primo) in the orchestra, cornet in the band, and sang tenor in the vocal numbers. Standing behind them was their father. Mr. Henry Noss, the musical director and cornetist in both the band and orchestra. He also sang bass in humorous songs and gave recitations in character sketches.

To the right, nearly as tall as her father, was Miss Flora Noss the oldest child. Flora played violin (secondo) and piano, as well as bass horn in the band. She was also a solo vocalist. Beside her was her younger brother, Master Frank Noss, who covered cello and side drum in the orchestra, and tenor horn in the band. He also sang and participated in the group's character sketches. On the far right was little Mary Noss, or May, who was skilled at the bass, violin, alto horn, cornet, organ, piano, triangle and side drum. She also sang soprano in the vocal numbers.

The only ones missing from this studio photo are Mrs H. Noss, that is Mary L. Noss, and little Bertha Noss. But they were not very far away. They may actually have been in the same room when the photo was taken, since the photographer of the musical Noss family was none other than Henry Noss of New Brighton, Pennsylvania. Negatives retained for future orders. Enlargements up to life-size by his new process. In this case the print would have to expand a great deal, because it is a tiny carte de visite photo, 2 ½ inches by 4 inches.

Henry Noss was born in 1837 in western Pennsylvania of immigrant parents from Bavaria. They settled in the borough of

New Brighton, which is on the Beaver River as it flows into the Ohio River, about 30 northwest of Pittsburgh. The area has abundant resources of coal and clay, and in the midd-19th century New Brighton developed many industries producing pottery, bricks, sewer pipe, glass, flour, twine, lead kegs, refrigerators, bath tubs, wall paper, steel castings, nails, rivets, and wire. Between 1860 and 1870 its population doubled from 2,001 to 4,037 residents. In the 1860 census Henry listed his occupation as

Painter, but by 1870 it changed to

Photographer. He was also an accomplished musician, and in 1861 served in the band of the 63rd regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

With his first wife, Mary Anna Noss, they had five children: Flora Jeanette Noss in 1865, Ferdinand P. Noss in 1866, Charlotte E. Noss in 1868, Frank W. Noss in 1870, and Mary "May" Noss in 1872. Sadly their mother Mary died in 1872, possibly at the birth of May.

Henry soon remarried to another Mary, Mary Lowrimore Noss and together they added Bertha Noss to the family in 1877. As was typical of many large families with a musical father, Henry recognized the potential ensemble he could make with his six children and began teaching them music. Before long all the Noss children displayed real talent on several instruments.

In the 1880 census, Flora is age 15, Ferd is 12, Lottie 10, Frank 8, and May is 6 years old. I think these ages fit neatly with the appearance of the children in the cdv photo, so I estimate it was taken in about 1880-81. Bertha would have then been only age three, and as I'm sure Henry knew well, keeping a toddler still long enough for a camera to capture an image was very difficult. The date of 1880-81 also fits with the closing era of the carte de visite which was replaced in the next few years by the larger cabinet card photograph.

The first report of the family as a musical group that I could find was a brief mention in the New Castle, PA newspaper in May 1881 that the Noss family "has acquired considerable fame in western Pennsylvania as musicians". New Castle was then a large town with a population of around 8,500. It was 22 miles upriver from New Brighton, and not far from Ohio. It was just the sort of place for Henry Noss to arrange a short concert tour to show off his children's musical talent. And selling souvenir cdv photos would be just the thing to pay for the trip.

Over the next few years the Noss family band increased the number of their performances, and the number of different concert venues beyond their home region in western Pennsylvania. By the summer of 1884 the Noss Family Concert Troupe, 7 in Number 7, were on stage at Hancock Hall in Ellsworth, Maine on the Atlantic coast, 800+ miles east of New Brighton. By this time "Baby" Bertha Noss, now age 7, had joined their program, playing triangle in the orchestra and bass drum in the band. She also played piano, organ, and sang solos, duets, and choruses.

In the winter of 1885-86, the Noss family traveled south to Wheeling, West Virginia. Then Frostburg, Maryland; Carlisle, Pennsylvania; and Freehold, New Jersey. They were now the famous Noss Family Novelty Concert Co. presenting musical and sketch entertainment. Mirth and music for everybody. Endorsed by Press, Public, and Pulpit. A FULL BAND, A FULL CHORUS, A FULL ORCHESTRA. Admission 25 cents, children 15 cents, reserved seats 35 cents.

|

Freehold NJ Monmouth Inquirer

25 March 1886

|

In October 1885 the Indiana, Pennsylvania Progress, quoted a review of the Noss family in the Alliance, Ohio newspaper.

The delightful entertainment given in the Opera House, on Saturday evening, by the Noss family, certainly entitles them to more than passing notice. The family consists of seven musicians, a fine band and first-class orchestra, a peculiarity of which seems to be that each member of the family is master of any instrument that is placed in hand. The musical selections were very fine and artistically rendered. As vocalists we may have seen the equals and even the superiors of the elder members of the Noss family, but we do not say too much when we say that there never was placed before an Alliance audience a music entertainment with more variety or which gave the audience more genuine satisfaction than the Noss family.

The singing and acting of little May and "petite" Bertha, the latter only 8 years of age, was marvelous, considering their years. They are really prodigies in their line. The medley overture was a fine selection to test the qualities of the little artist Bertha. She manipulates a canary whistle, cuckoo, fires a pistol, rooster crows, and beats snare drum, bass drum, and cymbals at the same time, police whistle and rattle, castanets, bells, metalaphone, pop gun, imitation clog dance with mallets, imitation thunder on bass drum, eliciting a storm of applause from the large audience.

The Dutch characteristic duet "Charlie and Katrina," by Misses May and Bertha elicited rounds of applause and was decidedly the neatest little piece of acting we have seen for many a day. Mr. Noss' parody on Barbara Freitchie was also a winning card, showing Mr. Noss to be a comedian of superior merit. This was the second visit of the Noss family in Alliance and the appreciation of the public was shown in the large increase of their audience over that in attendance at their former visit. We have no doubt but if the Noss family will favor Alliance with another visit, they will be greeted with a much larger audience than ever before.

The venue in Alliance was called an "Opera House", but it was nothing like a formal European-style opera house. It was a common title applied to a town's civic theatre in 19th century America. Often the town's city council occupied the same building as the theatre stage, as was the case in Ellsworth, Maine. The booking fees from traveling shows like the Noss Family Concert Co. were an important source of income for a small community that could not rely on property taxes.

Reading the reviews and notices, it is clear that Henry Noss was a creative entrepreneur who knew how to please his audiences. In Indiana, PA the Noss family played to a full house in 1885 and returned again in 1886. Mr. Noss used reviews from previous shows in other towns to pump up the ticket sales. It was also at this time that he engaged an agent to book shows and arrange for advance publicity in the newspapers. Little Bertha was proving to be an attractive draw.

Here she is at about the same age, seven or eight, as she would be in the performances of 1884-86. Mr. Noss has placed Bertha front and center next to the bass drum, which is properly decorated with the name Noss Family. The family group is now eight as Mrs. Noss is also in the picture with her husband. It's a carefully arranged arch with everyone else, except mother, holding a brass instrument. Along the bottom of the cabinet card photo are captions of everyone's name. From left to right: May, Flora, Mrs. H. Noss, H. Noss, Bertha, Ferd, Lottie, and Frank. The three youngest daughters wear coordinated ruffled dresses, while Flora, the oldest at about age 20, is dressed in a fashionable gown with a corsage pin to her collar. Mrs. Noss wears a more dignified dress in a patterned velvet fastened with at least 19 buttons. The brass instruments are the typical consort of piston valve saxhorns from Flora's bass to Frank's tenor and then Lottie's and May's alto horns. Ferd holds a standard cornet in B-flat, while his father has the higher pitched cornet in E-flat.

The back of this photo has a long presentation of the Noss Family Musical Novelty Co., Musical, Character and Sketch Entertainment, Brass Band, Chorus and Orchestra. Each member of the ensemble is described, from "Petite" Bertha to Mrs. H. Noss – stage manager. Two new instruments have been added: slide trombone, and clarionet (sic). Cabinet Photographs were available for purchase from Mr. Noss at 25 cents apiece, or $1.00 for a set of six. This suggests that five other different photos were produced at the same time as this group shot.

The Noss Family Band were not the only musical family playing a concert tour in the 1880s. I've featured a few on my blog.

Four Plus Three was about the four Simm sisters.

The Thomas Family Concert Co. was an African-American family band that toured in the 1890s. And

The Harry Sisters who were exact contemporaries of the Nosses and performed for a several years in eastern Pennsylvania. In 1886 and 1887 the Noss Family played shows in Carlisle, PA, the hometown of Prof. J. B. Harry and his three talented daughters, and I would expect they attended those concerts.

There are other family bands in my photo collection whose stories I've not yet told. Several were much larger ensembles than the Noss family of seven, and played just as many different instruments. In general the family bands/orchestras of this time only played arrangements of poplar music and nothing that resembled formal compositions from composers like Mozart or Beethoven. Since the performers were children, even if talented, the shows were designed around short pieces with no complex parts. Essentially family friendly fare.

But what set Mr. Noss' family apart was his programing of comic "Character Sketches". There are few descriptions of the Noss shows, but I expect they consisted of a series of short musical numbers interspersed with humorous skits. They used lots of costumes and make-up, and their jokes were likely based on comic stereotypes which would not pass the so-called "enlightened" standards of our 21st century. This was after all, the age of when minstrel shows were the dominant traveling entertainers, so it's quite possible that the Noss family may have performed some racist character sketches in blackface makeup.

|

Green Bay WS Press-Gazette

25 October 1889

|

Most of the family bands of this era only managed a short number of seasons on the stages of America's highly competitive theater circuits. Their wholesome music programs were not always worth a repeat visit the following year, and of course as children grow older, their cuteness fades. Yet by 1889 when the Noss family played Green Bay, Wisconsin, they were just hitting their stride. The advertisement announced a Noss Family "Ladies Gold-Silver Cornet Band, in their latest musical absurdity written especially to make you laugh. 'A Quick Match,' better than ever, everything new, immensely funny." They also featured a "Spanish Mandolin Orchestra" and a "Saxaphone (sic) Quintette", an band instrument that was then not familiar to the American public.

In 1889, Mr. Noss took his family band on a breathtaking concert tour of the United States. Just using the newspapers that published notices of their shows in 1890 from January to December, the Noss Family appeared in at least 85 towns. Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Alabama, Tennessee, Indiana again, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Missouri again for New Years Eve.

But wait, they weren't ready to go back home. January 1891 found them in Newman, Georgia followed by Troy, Alabama; then Asheville, NC; Albany and Savannah, GA; Barlow, FL; Morristown and Knoxville, TN; Norfolk, Roanoke, Staunton, and Richmond, VA. By then it was only mid-March. After more shows in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania, in August 1891 the Noss Family Band headed back to Wisconsin again. From September to December it was cities and towns in Minnesota, Montana, Manitoba, Washington, Oregon, and Nevada. They rang in the new year of 1892 in Los Angeles, California followed by Tucson, AZ; Las Vegas, Nevada; and El Paso, Texas in January. Altogether the Nosses played over 42 cities and towns in 1891.

It was exhausting to just compile this list. With more time for research I could probably add another couple dozen stops to their tour. What I found most interesting about the places where the Nosses performed is their tour of the Southern States. It was a surprising choice for Henry Noss who was a Union Army veteran.

It was about this time that Pennsylvania took census of its Civil War veterans for its pension accounts. In the 1890 Pennsylvania Veterans Report, beginning in August 1861 Henry Noss served 11 months, 15 days as a musician in the band of the 63rd regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. The band was dissolved by the War Department in August 1862 as a cost saving measure as Lincoln needed more riflemen and less musicians. But the following summer in June 1863 Henry reenlisted, joining the 56th regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteers as a private. It was a fateful choice as only a couple weeks later on July 1-3 his regiment fought in the Battle of Gettysburg.

There is no indication in his military record that he was wounded, but he left that unit in mid-August after serving 1 month, 16 days. The next year, in September 1864, he joined up again, perhaps to get a bounty bonus, and was a private in the 5th regiment of Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery. He was discharged in May 1865, one month after President Lincoln's assassination. I think taking his family on a tour of so many southern cities like Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Savannah, Norfolk, Staunton, and Richmond was an effort to explain the Civil War to his children. I also suspect he took his camera and recorded this grand trip in some gigantic photo album.

This was a family of eight people traveling by train for over two years on the theater circuits of America. Not many families could last two weeks! Bertha Noss, the youngest, was now age 13-14. Flora Noss, the eldest, was age 25-26. Henry Noss was 53-54 and his wife Mary was 50-51. The image of Bertha which opened my story came from this last cabinet card photograph which I think was taken during this period of their family life on the road.

There are no names captioned but they are not much older than the previous photo. From left to right are May, Frank, Mrs. Mary Noss, Mr. Henry Noss, Bertha, Ferd, Flora, and Lottie. The fashions are a bit more sophisticated, better suited for the young adults. Mr. Noss wears a formal suit. Ferdinand has on a white tie and probably tailcoat. Mrs. Noss seems attired in the same 19 button dress that she wore in the older photo. Notice that Mr. Noss has carefully chosen the same tropical forest backdrop.

By 1892, the Noss Family Band had been performing for 10 years. Hundreds of concerts, maybe a couple of thousand if we count matinees. How the children got a proper education is not known. At least they had seen more our country than most Americans. How long could Mr. Noss sustain a band like this? Something had to give.

On August 24, 1893 Flora Jeanette Noss, age 28, occupation musician, married James Lawrence Autenreith, age 29. a prominent merchant of New Brighton. Over 300 people attended the wedding at the Presbyterian church. Following the ceremony, the couple left for the world's fair in Chicago and afterwards would "spend several months traveling" before returning to New Brighton.

But the theater rule is that the show must always go on. So it was reported that a "New York lady" would replace Flora in the Noss family company.

_ _ _

|

Coffeyville KS Daily Journal

29 January 1895 |

By 1895 the Noss Jollity Company, as they now called themselves, still toured the country. Whether Mr. and Mrs. Noss accompanied them is unknown, but I suspect they stayed home in New Brighton. Their programs were now more of a musical comedy than just renditions of instrumental music. They advertised their new show, a Fantastic, Burlesque Musical Comedy, The Kodak, In Three Snap Shots, by Mark E. Swan. A positive novelty, all fun, no sorrow.

Hear the Musical Tennis Club

The Mandolin Troubadours

The Fairy Bells

The Saxaphone (sic) Quintette

See Baby Helen

Harry B. Roche

The Musical Donkey

The Rooster Dance.

* * *

|

Fresno CA Morning Republican

18 November 1900

|

But there was a new name, Helen L. Noss, a daughter born in 1889, age 11, ten years younger than Bertha. She was "at School", but surely this was "Baby Helen" listed in the Noss programs of 1895. In the next census of 1910, Helen was the only child left at home with Henry and Mary. She was then age 21, single and listed no occupation. Curiously, the census records asked women the number of their children and how many still lived. Mary Noss listed 2 children, but with only one living. These were the same numbers recorded in the 1900 census too, and the living child was surely Bertha Noss.

After looking at various family trees, not always an accurate source of family history, I believe Helen L. Noss may have been an adopted child of Henry and Mary Noss. She is not listed in the Noss family's cemetery where all the other children are buried. It's a mystery relationship that will have to remain unresolved until I learn more.

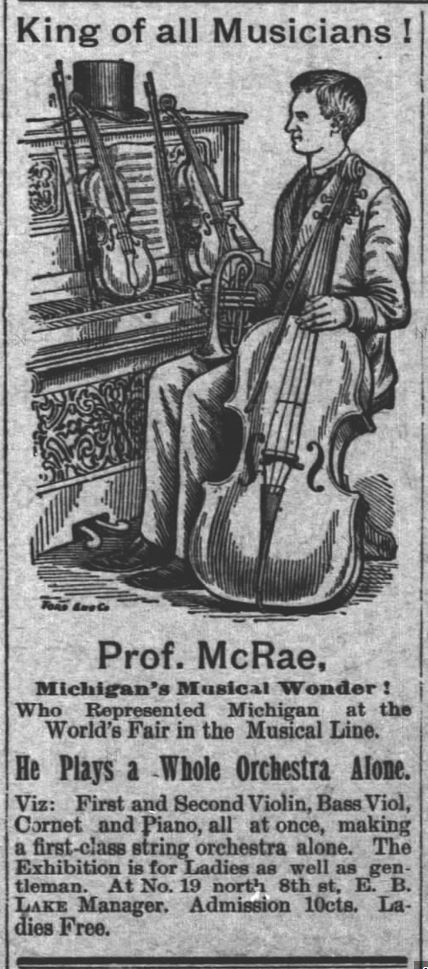

Over the next few years the family band evolved once again. Even though the Noss siblings pursued individual careers in theater, they still toured together on the vaudeville theater circuit as the Five Nosses. The Fresno, CA Morning Republican ran a clever vertical engraving of them promoting a concert. I believe Bertha Noss is at the top with Frank, May, Ferd, and Lottie Noss below her.