It's a small photograph

of a violinist dressed in formal tailcoat.

He stands with his instrument at his shoulder,

bow arm pulling down lightly,

almost as if he were

testing the tuning of the strings.

His gaze is direct but relaxed,

presenting an unaffected image

of a confident musician.

of a violinist dressed in formal tailcoat.

He stands with his instrument at his shoulder,

bow arm pulling down lightly,

almost as if he were

testing the tuning of the strings.

His gaze is direct but relaxed,

presenting an unaffected image

of a confident musician.

When it was taken,

unless you had met him,

or heard him in person,

you would not know

that he was the greatest Norwegian violinist ever.

His name was Ole Bull,

an artist who was worth remembering.

unless you had met him,

or heard him in person,

you would not know

that he was the greatest Norwegian violinist ever.

His name was Ole Bull,

an artist who was worth remembering.

This is part two of a series on Ole Bull.

Click here for part one.

Click here for part one.

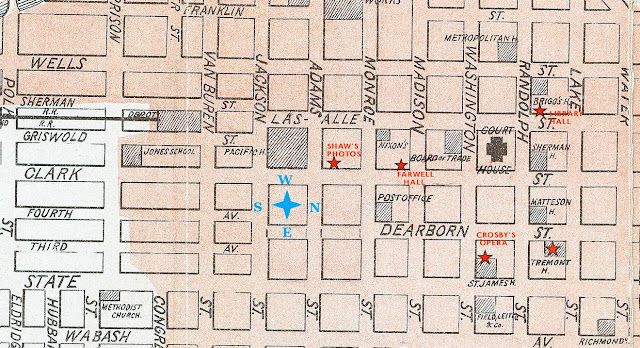

It was Monday, January 6th, the start of the second week of 1868. Despite Chicago's bitter cold, over 3,000 people had turned out to hear Ole Bull play his violin at the new Farwell Hall in the Young Men's Christian Association building. It was his first performance in America after his last concert tour in 1857. The celebrated Norwegian violinist enjoyed a very appreciative audience for his performance that evening, and no doubt invited them back for his second show on Tuesday night.

Unfortunately Ole's Tuesday concert would have to be canceled.

There was a problem with the Farwell Hall's stage.

It was no longer there.

There was a problem with the Farwell Hall's stage.

It was no longer there.

|

| Lawrence KS Tribune 8 January 1868 |

The fire began Tuesday morning around 9:00 AM. It was first noticed when workers at a printer's shop located on an upper floor of the Y.M.C.A. building saw smoke coming out of a trapdoor. It covered a large gaslight fixture which hung on the ceiling of the hall below. The top floor, not easily seen from the street, comprised a set of 35 lodging rooms rented out to about 60-70 men. At that hour, men were finishing their breakfast, and housemaids were cleaning rooms. Suddenly the cry went out, FIRE! Everyone fled the building trying to escape the smoke. One poor man suffering from smallpox was carried out on a stretcher. They did not have a moment to lose.

The fire spread very rapidly. Shortly after the fire company arrived with their "steamers", water pumps powered by steam engines, the upper floors collapsed into the hall. A few minutes later the fire dropped into the basement floor where a merchant stored flour, pork, and lard. The firemen could do no more than protect the adjacent buildings. The temperature was so cold that the water from their fire hoses froze into ice on the structure. Within hours the fire reduced the Farwell Hall into smoldering rubble. Amazingly, the only casualty was one fireman who injured, but not severly, while fighting the blaze.

The next day Chicago newspapers gave accounts which included detailed summaries of the fire and the financial losses. Between the value of the Y.M.C.A. hall and the other businesses located in the building, the fire cost roughly $300,000 in damages, but not all were insured. Though Ole Bull's troupe were fortunate to not be in the hall at the time, the fire destroyed the Steinway piano hired for his concert and valued at $1,500. Also reduced to ashes were a number of musical instruments valued at $600, which were left at the hall by the Great Western Light Guard Band that had accompanied the concert. Ole Bull promised to help recover their losses. Steinway offered a free replacement piano. It was good publicity for a new company.

Obviously his second concert would not go on as scheduled. What could he to do?

Maybe move to another theater?

Maybe move to another theater?

|

| Chicago Evening Post 8 January 1868 |

With less than 24 hours notice, Ole Bull's business manager. Mr. F. Widdows, hired the hall at the Young Men’s Association Library, called the Library Hall, formerly the Metropolitan Hall, for a replacement venue. It was advertised as Ole Bull's Third Grand Concert. Patrons who had purchased tickets to the cancelled second concert at Farwell Hall were allowed to exchange them for the Library Hall performance. Ole Bull knew this place well as it was on this stage that he had performed on his 1857 tour. It was ostensibly a library, but it had a large lecture hall that could seat about 1,200.

|

| Chicago, Young Men’s Association Library aka: Metropolitan Hall or Library Hall Source: Chicagology.com |

The program was not the same as the first concert. The two vocalists, Madame Charlotte Varian and Signor Ignatz Pollak sang different opera arias. Madam Varian's husband, the pianist Edward Hoffman, would perform (but not "sing" as erroneously stated in the advert) a piece by the American composer, Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Ole Bull gave three selections. An "Adagio Expression" and "Bell Rondo" by Niccolò Paganini, and two of his own compositions, "The Nightingale Fantasie" (by request) and "Siciliano Tarantille," both accompanied by the orchestra, presumably on a few borrowed instruments.

The reviewer in the Chicago Evening Post praised the performance in an effusive, embellished style, typical of newspaper writing of the time.

"The grand, fascinating element of Ole Bull's playing is his identification of his own personality, in all its varied wealth of resource, with his instrument. The instrument is but his longer arm, his more supple fingers, his all-assimilating imagination, and lively charming fancy, his depth of human feeling and inspired reach of human thought—all made vocal as if by a more than human tongue, voice full with airs of Paradise.

"With all previous violinists—even Vieuxtemps— the phrase, "the violin speaks," seems farfetched and empty. There is a deep gulf between the reality and it. But in Ole Bull's hands the violin does literally speak,—not, of course in articulate words, but no less potently and intelligibly and inspiringly, in the inarticulate language of passion and sentiment and cunning art, which voices our heart's profoundest thoughts, and repeats to us with something more than an echo of sound of nature and song of bird. This is what he does. How he does it would lead us too far, and quite uselessly, into the trite realm of the technical..."

Farwell Hall was a new building, opened just a few months before in September 1867. There was a lot of speculation about the cause of the fire. Perhaps the gaslight. Maybe a dropped cigar. Nothing was ever determined. But the building's catastrophic collapse revealed hidden design flaws that raised concern for public safety. The reporters pointed out that had the fire started during the previous evening's performance, many lives would have been lost. The building would be rebuilt, stronger and with better fire protection.

It was a testimony to Ole Bull's willpower and musical skill that he was able to play the following day. After the Wednesday concert, his tour would take him to Davenport, Iowa to open a new opera house, and then to Wisconsin. He would return to Chicago in a few weeks.

The photographer of Ole Bull's carte de visite, the second of two in my collection, was William Shaw. His establishment, Shaw's Mammoth Photograph Rooms, was located at 186 South Clark St. Chicago, Illinois, a short walk from Ole's hotel, the Tremont House. I featured his first cdv in Ole Bull, Adventures in America, part 1. The back of this one has an ornate cartouche around the photographer's logo with two cherubs working a camera and holding a small picture.

The 1860s and early 1870s were the golden age for carte de visite photographs, especially those of celebrities like Ole Bull. The cdv was the first type of photograph that could be easily reproduced. Thousands of images of royalty, politicians, generals, authors, and entertainers of all kinds were mass produced with this method. It created a new business opportunity for many men, and a few women, who took up photography as an occupation in this era. Mr. Shaw advertised that $12 would buy a hundred photos. No doubt Ole Bull thought it a good investment.

Before Ole Bull's return to Chicago, Mr. Widdows had concert notices printed in the papers. It was the same lineup of artists, accompanied again by Mr. A. J. Vaas leading the Great Western Light Guard Band. This time the venue was not the Library Hall but Crosby's Opera House, around the corner from the Tremont House where Ole Bull stayed. They would be his "Grand Farewell", "positively Ole Bull's last concerts in Chicago." This marketing phrase was frequently used by concert promoters to draw attention to a show. It's a gimmick still used today.

Crosby's Opera House was part of a five story building decorated in the Italian style. It opened on the 20th of April 1865, just a week after the assassination of President Lincoln. On the ground floor was a first-class restaurant with expensive plate glass windows running along the 140' front. Inside was a "magnificent marble soda fountain, with pure silver trimmings and attachments, the whole costing not less than $1,500. This is the only fountain in the country from which soda is drawn from porcelain cups. On the opposite side is a marble counter, with show-cases, devoted to the sale of cigars and bouquets." Below the building were, "Wine cellars, store-rooms, ovens, confectioneries, and pastry rooms, steam boilers, ranges, boilers, and labor saving contrivances, the latter operated by a steam engine." People lined up to indulge themselves in gastronomic delights.

|

| Exterior of Crosby’s Opera House Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1868 Source: Chicagology.com |

The following day, 21 April 1865, Crosby's Opera House, which was placed at the back of the building, put on a performance of Giuseppe Verdi's Il Trovatore. In December 1867 when Ole Bull arrived in Chicago, the opera house was occupied by a producion of Undine, an opera by the German composer, Albert Lortzing (1801–1851). Either before or after the opera, the "Grand Viennoise Ballet" performed a separate program. Tickets were $1.00, no extra for reserved seats. The hall had seating for 3,000 people.

The website Chicagology.com provided an illustration of the interior of Crosby's Opera House showing the stage and orchestra pit as Ole Bull would have seen it. It appears to be a vocal recital. Next to the singer is a pianist accompanying her on a so-called "square piano" (actually rectangular) which was then the design for concert grand pianos, and is very like the Steinway piano destroyed in the Farwell Hall fire. It's curious that later this year, Ole Bull would pursue getting a patent for his own invention of an improved piano soundboard based on his knowledge of violin construction.

Ole Bull's first concert at Crosby's Opera House was set for Friday, January 31. He probably expected that it would an ordinary performance without too much excitement. But on Wednesday evening, 28 January 1868, only a couple of blocks away on Lake and Wabash, two separate fires destroyed three business blocks. Smoke was spotted at one business establishment at about 7:00 PM. It quickly spread to adjacent buildings. Than at 8:40 another fire started on the next block. Firemen were severely hindered by the winter temperature, as water froze in the fire hoses causing them to burst. Despite the cold, thousands of people turned up to watch the conflagration consume over 500 feet of storefronts. Twenty-two businesses were destroyed. Hundreds of employees were put out of work. Estimates put the total loss at over $3,000,000.

_ _ _

Ole's final farewell concerts in Chicago went on without mishap,

but his proximity to these fires surely tested his fearless disposition.

but his proximity to these fires surely tested his fearless disposition.

Ole Bull was now 58 years old, the same age as the great Paganini when he died in 1840. For over 30 years Ole had toured as a concert violinist. In 1837 on his first successful concert tour in Britain he performed 274 concerts. This success brought invitations to play in Germany and Russia which prevented him from returning to Norway. Tragically his father died that year without ever once hearing his son Ole perform in concert.

In 1836 at the start of his career he married Alexandrine Félicité Villeminot in Paris. Over the next few years they had six children, but three did not survive infancy. His fourth child, Ernst Bornemann, was born in 1844 while Ole was on his first American tour, and died at four months of age. Ole did not learn of his death until six months later. His constant touring put great stress on his marriage. Alexandrine, called Félicité, suffered from a "nervous condition" and sadly died in February 1862 at age 43.

After numerous final farewell concerts, Ole Bull left New York for Bremen, Germany on 12 June 1868. By strange coincidence, as he had arrived in 1867 on the SS. Russia, this time he left on the steamship America, a paddle wheel ship. By returning to Norway, he was able to celebrate the wedding in August of his youngest daughter, Lucie Edvardine Bull, to Peter Jacob Homon, a prominent lawyer in Norway.

It was a brief stay as in October he was back in the United States for another tour, this time beginning in Boston. No sooner had he arrived than he learned of the tragic suicide of his new son-in-law. Newspapers reported the cause as "temporary insanity."

His concert tour kept to a tight schedule. By the end of November, Ole was playing in St. Louis. The next concert was on December 3 in Louisville, Kentucky. To get there he and his troupe traveled via a steamboat that went down the Mississippi River and then up the Ohio River.

On the next day following that concert in Louisville,

Ole Bull's company continued on to Cincinnati.

Unfortunately he would be delayed.

Ole Bull's company continued on to Cincinnati.

Unfortunately he would be delayed.

There was an accident

on the river trip.

And a fire.

on the river trip.

And a fire.

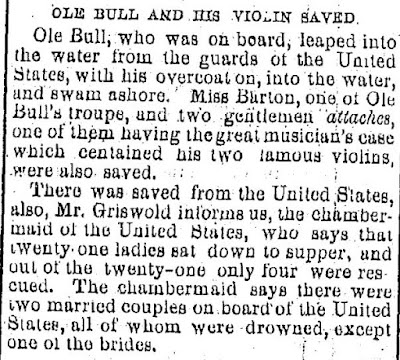

It happened on a cold night, Sunday, December 4th, 1868. Ole and company were aboard the steamboat America cruising upriver to Cincinnati. It was a 315' long, wooden hull side-wheel packet steamer with two main decks. It was part of the U. S. Mail Line, a large inland shipping company that provided a service connecting America's major river ports to the railway lines. The America's companion steamboat in the line was the United States, a bit shorter at 294 feet, but just as richly outfitted as a first-class vessel. It was heading downriver to Louisville. Both steamboats had experienced captains, crews, and pilots. They routinely passed each other on the Ohio River following a protocol of steam whistle signals. But for some reason that night the signals were misheard. The two boats, which were traveling in opposite directions near Warsaw, Kentucky, suddenly found themselves on a collision course. It was too late. Neither steamboat could turn or stop.

It happened about 11:15 PM when many people on board the two river craft had retired for the night. Others, like a bridal party were still awake, enjoying a late supper. Instantly there was chaos. The United States had a large number of oil barrels stowed in the bow, and both boats carried cargo of cotton and whiskey. The collision tossed the barrels into the river where sparks from the steam engines set the oil ablaze. As the crew and passengers jumped overboard into the freezing water, they now had to contend with a deadly fire too.

On board the America, Ole and his troupe rushed to escape. Fortunately Ole had not undressed. He jumped into the water and managed to get to the riverbank without much difficulty. His company's assistants saved his two violin cases, but he professed to be not worried. "I can play on some other fiddle if I do lose these two," he remarked. Miss S. W. Barton, the soprano with his troupe this season, was asleep in her stateroom, unaware of the danger. She had to be physically carried off the boat. The rest of the ensemble made it to safety, but their baggage and costumes were lost.

|

| Cleveland Plain Dealer 8 December 1868 |

Just like the reports on the Chicago fires, the newspaper accounts of this calamity on the Ohio River were amazingly detailed and thorough. There were long lists of passenger names with their occupations and hometowns. Precise tallies of costs and insurance values. The first estimates of casualties from the collision of the steamboats America and United States were above a hundred dead, sometimes as many as 150. But many names on the manifests were incorrect as some people had either left at the previous landing or not yet boarded. Historians now put the number at 74 lives lost.

Not surprisingly, Ole Bull would not let a near-death accident stop his show. Even though the accident had canceled his first concert, when he and his troupe reached Cincinnati, they went straight to the theater. Apologies were made for their missing costumes and concert attire, but his concert went on. His first encore was his rendition of "Home, Sweet Home", the second encore was his composition, "The Mother's Prayer". He later added "The Last Rose of Summer" and the "Arkansas Traveler." The audience loved it.

After Cincinnati, the troupe played Wheeling, West Virginia. Then on to Pittsburgh and New York where Ole stayed, playing more concerts over several weeks. In June 1869 he returned to Norway. By one account, during his lifetime Ole made nine trips across the Atlantic between 1843 to 1879. Sadly in that spring of 1869 he received the harsh news that his youngest daughter Lucie, who had married the previous August only to lose her husband to suicide, had died in March.

The next year, 1870, brought a happier promise as Ole married Sara Chapman Thorp, (1850–1911). She was 19, he was 60. Their wedding vows were first exchanged in Norway and then a second time in September in Madison, Wisconsin. In March 1871, Sarah gave birth to their daughter, Sara Olea.

In the summer of 1871 Ole Bull and his wife were staying in a house in West Lebanon, Maine. In the long digests of news from around the nation and the world, newspapers ran short reports that Ole was seriously ill. He "fell in a fit in the door yard of his residence". Friends were alarmed, the cause was thought to be "congestion of the brain." His condition was critical. Doctors advised that he stop performing.

By October he was thought to be recovering. There were rumors he might start a new tour. Maybe in a month or two.

Perhaps it was better that Ole

postponed his concerts that autumn.

Had he been in Chicago in October 1871,

his good luck might have run out.

postponed his concerts that autumn.

Had he been in Chicago in October 1871,

his good luck might have run out.

The Tremont House,

Ole Bull's favorite hotel,

was having a small problem

booking reservations.

Ole Bull's favorite hotel,

was having a small problem

booking reservations.

| |

| Chicago in Flames Scene in Dearborn St., Burning of the Tremont House 9 October 1871 Source: Chicagology.com |

Stayed tuned next week

for one more photo

and the Final episode

of my series

Ole Bull,

Adventures in America.

for one more photo

and the Final episode

of my series

Ole Bull,

Adventures in America.