The first postcards

were a medium made for tourism.

After

arriving at an exotic vacation destination

travelers always felt a need

to write to the folks back home.

"Weather is too wet/dry/cold/hot as

Hades."

"Place is incredibly beautiful/horrible/dull as dirt."

"Having

a wonderful/okay/miserable time."

"Here's a picture of something

funny/pretty/unusual that we saw!"

For many far-off places its local street musicians

served as suitable

scenic subjects for a vacation postcard.

Musicians like the

Italian bagpiper player

on an 1898 card,

or the postcard set of

Parisian ballad singers

from 1901.

And on the streets of Jacksonville, Florida in 1913

it was a brass band of twelve African-American boys.

They

may have had their picture taken

for a holiday visitor's postcard

but

it's quite possible they were tourists too.

This is a story about a postcard photo puzzle.

The group of young black musicians stand outside the veranda of a large

stuccoed house or hotel. Behind them are a few white children and adults

partly hidden in the shade from the porch. It's a typical 12 piece brass band

with cornets, slide trombones, alto horns, and tubas and two drummers. The

boys' ages range from around 8 to 16. An older man, perhaps 30ish and wearing

a bowler hat, stands at the back along with a younger man in cap and bow tie

who holds a cornet. The boys are dressed in blousey knee pants, and most have

uniform coats trimmed with fancy button braid. All wear either caps or cadet

hats. The people on the veranda are smiling but the boys in the band mostly

show a serious expression.

It's a small photo printed on standard postcard stock with a wide border where

someone has written a caption in ink.

Scott's Dixie Band Jacksonville Fla

In the upper right in faded ink is

Mr & Mrs Scott

with a slash directed into the photo. In the upper left corner is a date

1913 written with a

ballpoint pen, probably by the dealer I bought it from. The back of the card

shows that it is correct as the postmark is from Jacksonville, Fl on February

11, 1913 at 5:30 PM. The card is addressed to Mr. Frank Longman of

Packard St., Ann Arbor, Mich.

Still on deck

but waiting for

the clouds to

roll

by. Best wishes

to your wife & Mr

& Mrs.

Eberbach in

which Mrs Scott joins

Yours Evart

With so many dates, names, and places this postcard doesn't seem like much of

a puzzle. Except that the writer gave the boys' group a name,

Scott's Dixie Band, which was actually not their real name. To prove

that will require some photo detective analysis.

I'll begin with the recipient of the postcard.

In the 1910 US Census, Frank C. Longman, age 27, was living with his

wife Edythe N. Longman, 28, on Packard Street in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was

the home of Edythe's parents, Edward H. Eberbach, age 61, and his wife, Mattie

Eberbach, 60. Mr. Eberbach's occupation was listed as

Retail Merchant in Hardware. In the Ann Arbor city directory

this proved to be a large firm dealing with brass, copper, and galvanized iron

sheet metal work. His son-in-law, Frank Longman, worked as an

Attorney-at-law in General Practice.

|

1910 US Census, Ann Arbor, Michigan

|

Ordinarily that might be all the research needed, but postcards like

this get saved for a reason so I was curious if there was anything more to

connect Frank to this postcard. It turned out that there was.

Football.

Frank Chandler "Shorty" Longman

was born 7 December 1882 in rural Kalamazoo County, Michigan. In 1903 he

entered the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and became a star fullback

with the Wolverines football team for three seasons. Following his

graduation in 1906 Longman took up coaching, first at the University of

Arkansas, then at the College of Wooster, Ohio where he accomplished the

supposedly impossible by defeating Ohio State. In 1909 he became head coach at

Notre Dame and in his two seasons there set a winning record which included an

11 to 3 victory by the Fighting Irish over his alma mater, the Michigan

Wolverines, which was still led by his former coach, the celebrated Fielding

H. Yost. The legendary Notre Dame football star Knute Rockne played as a

freshman on Longman's 1910 team. Rockne would go on to coach the Fighting

Irish from 1918 to 1930.

It seems unlikely that Frank Longman found time to get a law degree while at

Notre Dame, so I suspect his occupation recorded in the 1910 census is an

error. In later documents, like his 1918 draft card and the 1920 census, under

employment he listed paving contractor which in this era probably paid

much more than football coaching did. Tragically, Longman died in April 1928

of tuberculosis at the young age of 45.

|

|

1913 Ann Arbor, Michigan city directory

|

The sender of the postcard was a bit more challenging to identify, mainly due

to bits of old black album paper stuck on the postcard covered his signature

which required careful removal. The reason it was sent to someone in Ann Arbor

was because he lived in Ann Arbor too. Evart Henry Scott was born in

Ohio in August 1850 and married to Sarah E. Scott. In February 1913, Evart,

not yet age 63, ran his own fruit farm in Ann Arbor. His name was associated

with a local Ann Arbor agricultural association, which in 1910 may have sent him to Tampa, Florida acting as a representative for Michigan's

fruit growers. In the 1913 city directory for Ann Arbor his business is listed

as Real Estate, but his occupation in the census was Farmer.

Evidently his fruit did alright as his name appeared in reports on civic

activities in Ann Arbor and at the University of Michigan.

|

Detroit Free Press

3 November 1902

|

The reason Mr. Scott was sending a postcard to Frank Longman was that Evart

was a BIG fan of football. Specifically his hometown team, the Michigan

Wolverines. In November 1902, the year before Frank started his freshman

year at the University of Michigan, Evart captured some unexpected fame

reported in newspapers around the country from Los Angeles to Boston.

Following an important game with Michigan's rival, the Wisconsin Badgers,

Evart was celebrating the Michigan victory at swank Chicago hotel. Challenged

or inspired by his companions, Evart suddenly dove into a large Italianate

water fountain. After a futile effort to swim in the three-foot deep pool and

catch goldfish in his hat, he began to sing

"Oh, ain't it great, just simply great. To wipe Wisconsin off the

slate." Pulled from the water by his brother and several friends, he was

promptly taken off to bed.

_ _ _

With that level of enthusiasm for football, it's no surprise that Evart

would have a friendship with a college football star like Frank Longman. I

bet after returning to Ann Arbor he even brought back a couple cases of

oranges for Frank and his wife. And the story also suggests Evart Scott

enjoyed a good joke on himself which I think explains his fanciful caption

on the postcard, Scott's Dixie Band. In the context of a traveler

writing to a close friend, it's clear he was using an old minstrel show

phrase to make a little jest and show friends back home a bit of Florida's

peculiar attractions.

My collection has dozens of postcards and photographs of boys' brass bands.

Most are from the United States but many come from around the world too.

Beginning from the 1870s teaching boys a musical instrument was promoted as a

way to focus their attention, keep them pointed toward a positive lifestyle,

and give them training at a useful trade—music making. Many communities

considered it a valuable social assistance for disadvantaged youth. However

for orphaned or abandoned children membership in a band was beneficial as a

refuge from hardship and as a pathway to an education and a better life. This

was especially true for African-American children in the shameful Jim Crow era

of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The boys pictured in this small postcard from Jacksonville were clearly not

from rich families if they had any family at all. Their deadpan demeanor is, I

think, the result of living at a time when American society, particularly in a

southern state like Florida, operated under racist rules and oppressive laws

that were very different than those applied to the white folk standing behind

them. These boys were not allowed to come onto the porch. No one gave them a

glass of lemonade or snack from the hotel's kitchen. After their concert,

Evart Scott got a souvenir picture of them, but the boys in the band likely

never saw a copy of their photo. They were very aware of that invisible

red line that bigotry and discrimination drew between their performance on the

pavement and the white folk listening on the shady veranda.

It is because of this harsh history and much more that photographs of

African-American culture from this period are very rare. Mr. Scott made up a

name for the boys' band probably because he never learned what they called

themselves, so even with a date and location they remain anonymous.

Or do they?

The postcard photo was taken in February 1913. In the following summer of

1914, I believe that a few of these boys were members of a larger band that

traveled from Charleston, South Carolina to London, England. A century later I

featured their postcard in my story entitled

The Jenkins Orphanage Band.

This was not a British navy band but an American boys' band from Charleston,

South Carolina. They were all

inmates, as the census labeled them, of

the

Jenkins Orphanage. It was founded by the

Reverend Daniel J. Jenkins

(1862-1937), a Baptist preacher and native of South Carolina. One cold winter

in 1891 while collecting wood at the train yard in Charleston, he encountered

a group of destitute boys huddled in a boxcar. Hungry and homeless, these

small orphans inspired Jenkins to take them into his own family. His simple

act of charity became his calling in life and brought forth such a boundless

compassion for the homeless black children of his community that it led him to

create an institution that could provide for their welfare and education.

According

to census records, by 1900 there were nearly 70 negro boys and girls in Rev.

Jenkins' orphanage. Like many children's homes of this era there was a school

band, as music was considered a standard requirement for a proper education

and learning a musical instrument offered a practical trade skill. An orphans'

band also proved very helpful in soliciting donations for an institution so

very low on Charleston's list of charitable organizations in the 1890s. Rev.

Jenkins was a tireless fundraiser, making countless speeches and appeals for

funds to support his work. He recognized that patrons outside of Charleston

enjoyed hearing his talented charges, so he shrewdly arranged for the band to

accompany him on his campaigns around the country, particularly in the North

where there were many more sympathetic benefactors for negro charities than in

the South.

In 1914 Rev. Jenkins arranged for his orphanage's boys' band, called

"The Famous Piccaninny Band", to perform in London at the Anglo-American

Exposition. In May 1914 Rev. Jenkins, his wife, and a band of 23 young men and

boys booked 3rd class passage to Liverpool and arrived just in time for the

exposition's opening on May 14th. The show promised spectacular exhibits about

the Grand Canyon, the new Panama Canal, and a "six acre realistic replica of

Greater New York City with its hundreds of skyscrapers". There was also the

101 Ranch Wild West Show from Oklahoma and "hordes of other startling

novelties" of which the Jenkins Orphanage Band would play a small part. The

exposition was expected to run all summer and draw large crowds at its park

located in Shepard's Bush.

Unfortunately, a war intervened. At the beginning of August, when Austria

mobilized its army against Serbia, which mobilized Russia's military, which

set Germany to invade Belgium , which activated the allied forces of France

and Britain, the public's attention shifted away from world fairs to warfare.

Rev. Jenkins and his family managed to quickly secure a return ticket, but his

boys' band was stuck and was unable to get back to Charleston until

mid-September. My full story about them is at

The Jenkins Orphanage Band

so I won't repeat it here.

What's important to this story on the Jacksonville boys' band is that by 1913

the Jenkins Orphanage Band was already a veteran touring act. For many years,

mainly during the summer months, the boys band regularly traveled to events at

large cities like New York, Washington, and Philadelphia. They appeared at the

1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY; the 1904 Louisiana Purchase

Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World's Fair; and supposedly marched

in President Taft's 1909 inauguration parade. The proceeds from their band

concerts became a major source of income for the orphanage, so Rev. Jenkins

soon hired another band leader for a second band. Eventually there would be as

many as four musical groups on tour. They would often stay at the YMCA, the

Young Men's Christian Association, like the one pictured above in St.

Petersburg, Florida - The Sunshine City which date from the 1920s.

For much of the early 20th century, St. Petersburg was the most popular

tourist destination in Florida, and the height of its season was during the

wintertime when people from up north, like Michigan, traveled south for the

relative warmer climate. Since the Jenkins Orphanage had a connection with

Florida, I wondered if I could find any reference to a tour in February 1913.

|

Miami FL News

28 February 1913

|

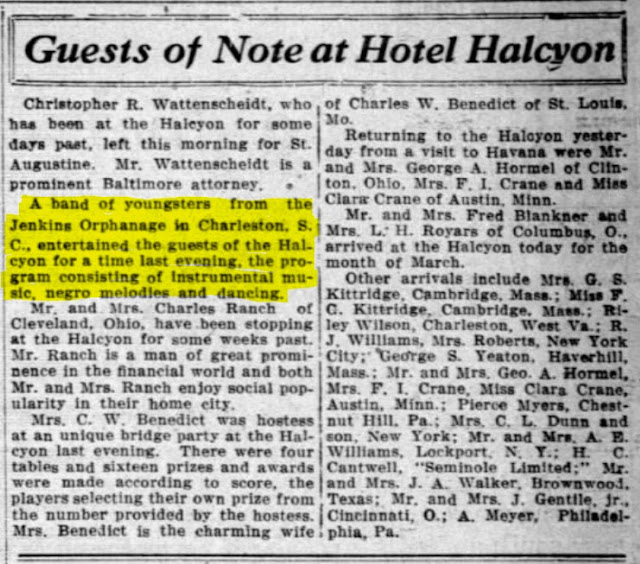

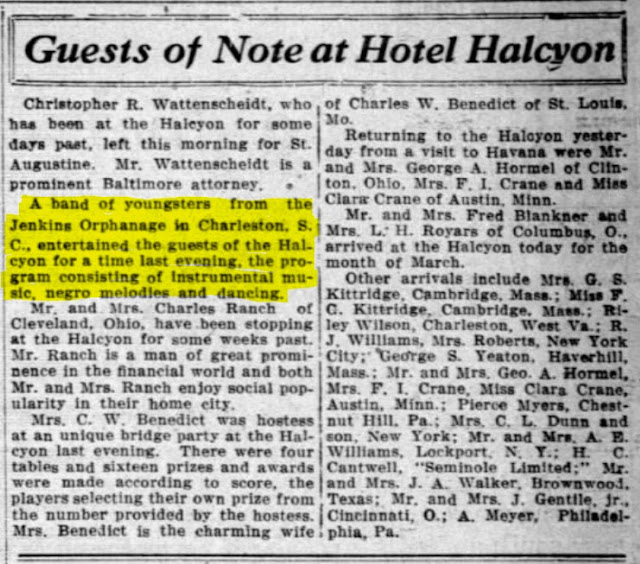

The Daytona Beach Daily News reported that the Jenkins Orphanage Band

was in the city on 13 February 1913. This is only 90 miles south from

Jacksonville. Then in the 28 February edition of the Miami News, a

society column from the Hotel Halcyon made note that "A band of youngsters

from the Jenkins Orphanage in Charleston, S.C., entertained the guests of the

Halcyon for a time last evening, the program consisting of instrumental music,

negro melodies and dancing." Mr. and Mrs. Scott are not mentioned in the list

of guests, but everyone is identified with their hometown and there are

several people from Massachusetts, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West

Virginia. Miami was, of course, the shipping port used for travelers going to

Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other tropical places in the Caribbean. What went

unmentioned in the report is that the colored boys of the Jenkins Orphanage

Band were not allowed to stay at the Hotel Halcyon.

|

Indianapolis IN Freeman

30 August 1913

|

Later that year in August 1913, the The Freeman,

an Illustrated Colored Newspaper, published in Indianapolis for a

national African-American readership, ran a short notice about a vaudeville

trio called the Whitman Sisters. The report mentioned "Prof. Eugene Mikell

formerly leader of the Globe Theater orchestra in Jacksonville, Florida and

his band of thirty-five orphan boys ... known as (the) Jenkins Orphan Band."

This was an exciting connection because Eugene Mikell was once the star

musician of the first band organized by Rev. Jenkins.

|

1913 Jacksonville FL city directory

|

The 1913 city directory for Jacksonville, FL lists a "*Eugene F. Mikell (m),

musician, h 1218 E Duval". {The asterisk* before his name denotes "colored"

and was applied not just to names but to all the businesses, churches,

societies, and city parks in Jacksonville.}

|

New York Age

30 January 1932

|

Francis Eugene Mikell, (1880-1932) was a very talented musician who

played both violin and cornet. In 1917 he was appointed bandmaster to the 15th

New York National Guard and later lead the 369th Infantry Regiment Band during

and after World War One. He and his fellow bandleader,

James Reese Europe

(1881–1919) are credited with helping to first introduce America's jazz music to Europe

through this extraordinary band which was made up of the best black musicians

in America. Lt. Eugene Mikell died in 1932 at age 51.

Mikell's background is not yet in Wikipedia, though it deserves to be, as he

organized or played in dozens of bands for vaudeville theaters, minstrel

shows, schools, and most importantly in the Jenkins Orphanage Band as both a

young musician and later as a leader. Since he was living and working in

Jacksonville, Florida in 1913 it seems very likely that a traveling unit of

Rev. Jenkins' orphan band would stop there to play and maybe collect donations

from the nice people of Michigan.

_ _ _

|

Jenkins Orphanage Band

circa 1930s

Source: The Internet

|

After Rev. Jenkins' death in 1937 his orphanage closed the facility at 20

Franklin Street in Charleston in 1939 and moved to North Charleston where his

work continues today as the Jenkins Institute for Children. Recently I

discovered a photo taken in the 1930s which shows the band in sharp modern

band uniforms. On the left is a pastor, not Rev. Daniel Jenkins but a

different man, who looks very like the man in the bowler hat in Mr. Scott's

postcard. On the right another man holds a dark banner that reads "Jenkins

Orphanage Band representing a Worthy Home for Children".

Until a day ago I had not noticed that the man in the bowler hat is

holding a furled banner which has lettering. Could this be a banner of the

Jenkins Orphanage Band?

It's all very circumstantial evidence. At this distance in time there is

no one alive who was there that day. All we have is Mr. Scott's wiseguy

caption, and I think I've proved Evart was making a joke. I won't belabor

this story with how many false trails I've followed searching for a black

man in Jacksonville named Scott who might have led a boys' brass band.

Suffice it to say, there isn't one.

Maybe the band's banner was not opened when Mr. Scott first heard the

boys play. Maybe it says something else. Maybe I have it wrong and this is

another boys' band unconnected to either Rev. Daniel Jenkins or Prof.

Eugene Mikell. Maybe it's all just conjecture.

But then again maybe it's right.

Over the many years Rev. Jenkins that campaigned for his foster children, boys

and girls, he developed the talents of thousands of young musicians, both

amateur and professional. In 1913 the term "Jazz" or "Jass" was not yet

recognized as a musical term. However the music that the Jenkins Orphan Band

played was a Charleston synthesis of ragtime, blues, and older African forms

that had a strong influence on other centers of African-American music like

New Orleans and Chicago. Many scholars of music believe Charleston's Jenkins

Orphanage deserves a place as one of the originators of jazz music. Several of

its "alumni", like trumpeters William "Cat" Anderson and Jabbo Smith; pianist

and singer, Tom Delaney; and guitarist, Freddie Green, became celebrated jazz

artists.

In November 1928 Fox Movietone News produced a short sound film of the Jenkins

Orphanage Band to play at its movie theaters. The Moving Image Research

Collection at the University of South Carolina has restored the film as the

Jenkins Orphanage Band - Outtakes

. The full 11 minute video has several out-takes of the band repeating one

tune. Skip to about 3:07 and the camera moves for

some great closeups of the individual musicians. There is even some dancing at the end to

demonstrate the origins of the Charleston dance craze. It's not sophisticated

or even polished music, just raw youthful energy, but it's still authentic

entertainment. It's a band worthy enough to be on a picture postcard to send to the folks back home.

* * *

* * *

This is my contribution to

Sepia Saturday

where the street fair is on all weekend.

.svg.png)