I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up

and live out the true meaning of its creed:

‘we hold these truths to be self-evident – that all men are created equal’.

and live out the true meaning of its creed:

‘we hold these truths to be self-evident – that all men are created equal’.

Martin Luther King Jr. – “I have a dream” speech, 1963

This the third story of a 3 part series.

I recommend starting with the first one:

I recommend starting with the first one:

|

| Asheville NC Citizen-Times 3 June 1914 |

J. M. Washington, colored, to Vivian B. Alston, colored.

This brief line was not like the wedding notice found in The New York Age that finished my first story in this series, The Glee Club of East Palestine, Ohio - part 1. Here James' first name is missing and his middle initial was incorrect, while Vivian's middle initial and surname are at least properly separated by a space which the New York Age mistakenly reported as "Balston." But the Age did include details like James was a graduate of East Palestine, Ohio and Miss Vivian a graduate of the Allen Home in Asheville and that they were wed June 2 at the First Baptist Church. All very useful information that helped me identify them in other records.

But in Asheville a single bureaucratic word was added

that made this record standout in stark contrast—"colored".

that made this record standout in stark contrast—"colored".

A century later it is difficult to describe how awkward, even offensive, this word is. Yet history does not allow us to ignore institutional racism and in fact I could not have done my research without taking advantage of this word. The name James Washington is shared by more men than I can count, yet I have been able to identify the young man in my photos from East Palestine, Ohio because in 1908 America marked people by the color of their skin. Sometimes it was "colored", or an initial C or B or M, or just an asterisk next to a name. It was an era when every government or official document included a line or box to indicate race.

In North Carolina the word was used everywhere. Parks, churches, restaurants, businesses, schools, libraries, and hospitals, not to mention public toilets and drinking fountains were labeled "Colored". The state mandated "Jim Crow" codes that defined racial segregation throughout every part of North Carolina society and assigned strict penalties for any infraction. These laws devised by white men effectively divided Southern culture into two separate communities. White people were pretty much free to go and do as they like without causing offence. "Colored" folk needed to know the right entrance to use at a theater; the right place to sit in a restaurant; where their children could play; and even how to speak to a white person in a deferential manner.

Going to school in East Palestine, Ohio, James Washington had a rare opportunity to experience a part of America where the rules of racism were less strict and the community was more accepting. No doubt Ohio had its share of prejudice and bigoty, but in 1908 it was not a society that blatantly placed restrictions and boundaries on people of color. So why did James return to Asheville?

Maybe because his family and friends were more important to him.

|

| Asheville NC Citizen-Times 18 December 1904 |

While James was in East Palestine high School, Vivian Alston was a student at the Allen Home School. Originally called the Allen Industrial Training School, it was established in 1887 by the Woman’s Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church as a private school to teach African American children to read and write. It was named after Marriage Allen, an English Quaker philanthropist, who donated money for construction of a dormitory building when it added a boarding school for girls. The teachers were white female missionaries so classes followed “Christian ideals” but there was also vocational training in domestic tasks such as cooking and sewing. The Allen Home School set high academic standards which let it train teachers too. It was became a state accredited private high school in 1924 and closed in 1974.

|

| Asheville Academy and Allen Industrial Home 1916 Asheville city directory |

Boys were allowed to take classes there as day students, and it's possible James attended during his middle school years. But it's very likely that he met her at the Young Men's Institute, the Y. M. I. where in December 1904 she and her brother sang for an entertainment there. When James returned to Asheville in the summer of 1910 before going to Raleigh to enter Shaw University, it seems likely he renewed a friendship with Vivian then. She may be part of the reason his time at Shaw was limited to just two or three years.

After their marriage they moved to 47 Circle St. on the east side of downtown Asheville, a very short distance from the home on Valley St. where James had lived in 1900 and close to his elementary school on Catholic Hill. In the 1915 city directory his occupation was listed as a porter for the Southern Railway. Curiously the address on Circle was also where James' mother, Lula (Louise) Sims, lived in 1910, presumably after her employment with families in Ohio and Massachusetts ended. [See the previous story in this series: The Glee Club of East Palestine, Ohio - part 2]

%20CLIP.jpg) |

| 1915 Asheville, NC city directory |

Despite its small population in 1915 Asheville was becoming a tourist destination in the region and could boast of 25 hotels, several offering high class service, and 92 boarding houses, many catering to seasonal visitors who came to Asheville for its cooler mountain summers. As a railway porter, James may have worked long days onboard trains serving the area, perhaps supplementing that occasionally as a hotel porter. He did find time for music and his name appears in notices for entertainments at the Y.M.I. where he sang in a men's quartet.

On 8 August 1916 there was a concert at Asheville's city auditorium of two hundred "colored" singers celebrating "the first Negro Folk-Song Festival". It was organized and led by Mrs. E. A. Hackley of Chicago who was on a mission to resurrect and present "negro folk-songs and plantation music." She was aided by Dr. J. W. Walker, a "colored physician" of Asheville who helped assemble a chorus of men, women, girls, and boys who learned the music in just two weeks. The audience was a rare mixed group of black and white patrons who were generous in their applause. I like to think James and Vivian Washington were part of that chorus. Sadly, though the organizers promised this concert would become an annual event in Asheville, it never did.

Meanwhile James and Vivian started a family and by 1916 had two children. But for some reason they left Asheville in the early half of 1917. This was actually fortunate as they missed a terrible tragedy that happened in November, not 300 yards from their home.

|

| Asheville NC Times 16 November 1917 |

Around 11:30 Friday morning, 16 November 1917, a fire swept through the Catholic Hill School where James had attended elementary grades. After teachers first noticed smoke coming from the basement it took 20 minutes before the firemen arrived, and then more time was lost laying out hoses up the hillside as the nearest fire hydrants were down below on Valley Street. Fanned by a strong wind the school building's roof and walls collapsed at 12:30. Though most of the students and teachers escaped, seven children perished in the fire and several more were injured. The school was totally destroyed. Afterwards the teachers and children moved into temporary classrooms set up in a nearby "colored" sanatorium. In 1922 a new school for African-American children, Stephens-Lee High School, was built on the site. Its construction cost $115,000. Seven years later in February 1929, a new high school for white children was opened. It cost $1.3 million.

In June 1917, like most American men between the ages of 18 and 45, James Aaron Washington registered for the draft as the United States prepared to join the war in Europe. He was living at 1810 Sharswood St. in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He listed as dependents his mother, wife, and two children and he was employed as a cook at a diner run by Henry Burns on Girard St. He was 26 years old, born on 1 May 1891 in Asheville. The lower left corner of his draft card was clipped to indicate to military administrators that he was of "African origin".

I looked up James' employer and discovered that Henry Burns' home residence was the same address as James'. I believe Henry was Lula Sims' father, which would explain why they were living there, but I was unable to find enough records to confirm that relationship. And in this case the huge Philadelphia city directory was not helpful to a genealogist as it did not mark people's race. However of the 15 men with the name Jas Washington in the 1918 directory only one was a cook and living at 1810 Sharswood.

|

| 1920 US Census Philadelphia, PA |

To make it more confusing the 1920 census for Philadelphia has James and Vivian living with three children, a son and two daughters, all born in North Carolina, the youngest at age 1 being marked as both Son and F (female). James is now age 28 and he works as a "R R C" at the "Terminal", which I interpret as railroad clerk at the Philadelphia train terminal. His mother's name was not Sims but was now Lulu Dyer, She was age 48, born in South Carolina and she had another son living with them, John C. Dyer age 19, born in South Carolina. Adding another layer to the household was an aunt, Catherine James (? or Janes), and a brother-in-law, B. P. Austin, which I think was another spelling error of Alston, Vivian's family name.

The reason the Washington family moved to Philadelphia in 1917 and remained there for 4 years are unknown to me, as are reasons that brought them back to Asheville in 1922 when they returned to 47 Circle St. James was now employed as a clerk at the "Ry M S" which stands for the Railway Mail Service. This work involved sorting mail at the Asheville train terminal or sometimes working on a post office railcar included on mainline train routes. Interestingly, his mother is living with them too and has taken the name Lula Washington.

%20CLIP.jpg) |

| 1923 Asheville, NC city directory |

The Washington family had added another child and no doubt found Asheville familiar and small after living in Philadelphia. The Asheville newspapers make no mention of James or Vivian, but in June 1921 there is a court notice that a divorce has been granted to George and Lula Dizer after 5 years of separation. A check of the city directory showed that Lula Sims lived at 47 Circle in 1910, and George and Lula Dizer lived there in 1911. [Figuring out name misspellings and phonetic homophones are just one of the many challenges my research encountered]

Sadly on 7 April 1926, Lula Washington Deyer (another misspelling of Dizer) died of cancer. James Washington provided the information for her death certificate. She was age 54. occupation: Domestic. Her father's name was Henry Burns.

James and Vivian stayed in Asheville for a bit longer, but in 1927 only James was listed in the city directory. He worked at the Service Drug Store, a "colored" pharmacy on the ground floor of the Y. M. I., but his residence was in Washington, D. C.!

* * *

When I first acquired the two postcards of the East Palestine High School Glee Club and Orchestra, the face of one young man fascinated me. Who was he? How did an African-American boy get to perform with white boys in 1908? Was it even possible to identify him? Needless to say this research involved a lot of detective work. None of the preceding history of James Washington came from Wikipedia or the New York Times or a family tree on Ancestry.com. It involved checking a lot of false leads and mistaken connections as well as triangulating locations in three states. However I am confident that I have correctly identified that young man and learned enough to describe some of his history behind these two photos.

But there is also a history in front of the photos too. It involves a connection that was so intriguing that I had to continue my research to prove it. It's a personal detail about James Washington that hinges on his middle name—Aaron.

Following the trail of little breadcrumbs of history is often very frustrating because most individuals share a name with dozens, even hundreds, of other people at any one time. Such is the case with tracking down James Washington. Fortunately America's institutional racism eliminated anyone who was not "colored." When he became a married man it narrowed the list to only those men with a wife named Vivian. But James' middle name eluded me as only occasionally did he use an initial A. Then I found his 1917 draft notice, carefully filled out by James Aaron Washington, who kindly gave enough information to confirm his identity on other records. But there was one problem. There was another James Aaron Washington. And this one had a more recent biography that was fairly well known. However it did not include enough family history to positively connect him to my James Washington. But after piecing together all the crumbs I determined that they were actually father and son.

In 1927 the Washington family moved to Washington, District of Columbia. This was probably a decision based on James' work with the U.S. Postal Service. By this time he and Vivian had four children, two daughters and two sons. Vivian Louise was then age 9; Placide was 8; Charles, the youngest, was 6; and James Jr. was 12.

%201136%20Columbia%20nw.jpg) |

| 1932 Washington, District of Columbia city directory |

It took a few years before finding the right place, but the Washingtons settled on a brick townhouse in the 1200 block of Columbia Rd. in northwest D.C. [The 1932 directory got the number wrong.] It was very close to the National Zoological Park, the Old Soldiers Home, and Howard University, one of the most prestigious historical black universities in America.

The family had not escaped racism by leaving North Carolina as James Jr. attended three schools in D.C. from 1st to 12th grade, all segregated for only Black children. As a young man he entered Howard University and graduated with a B.A. degree in 1936. Choosing to pursue a degree in law he was was awarded an LL.B. from Howard University School of Law in 1939 and a LL.M. from Harvard University in 1941.

During the war James Jr. served briefly as a second lieutenant in the army's chemical warfare service. But he found his true calling as an attorney, first working with the U.S. justice Department and then in 1946 becoming a professor at Howard University Law School. He also worked closely with other attorneys and in a 1942 case helped the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP, represent a black employee of the War Department who sought $5,000 damages after being struck on the head by a guard who prevented him from entering the department cafeteria. After filing the case, the "restrictions on service to Negroes at the cafeteria were removed."

|

| Staunton VA Daily News Leader 9 August 1950 |

In 1950 Gregory Swanson, a prospective student at the University of Virginia law school, was denied admission because of his race. He filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to prevent the university from barring Negroes. On the legal team representing Swanson were three attorneys from the Virginia conference of the NAACP; two from Howard University, George M. Johnson, the dean of the school of law, and James A. Washington Jr.; and a special NAACP attorney from New York City, Thurgood Marshall.

|

| Miami FL Times 6 October 1951 |

In October 1951, the United State Supreme Court heard a case from Negro public school students of the District of Columbia who sought a court order that would remove racial segregation from their school system. For many decades the Supreme Court had addressed the concept of "separate but equal" in several cases, always allowing states the right to set their own "equal accommodation" for segregated schools and other public facilities. But in this case the plaintiffs asserted that "segregation of American citizens is of itself wrong and unconstitutional and in violation of the fifth amendment to the constitution of the United States." Among the group of seven lawyers representing the students was James A. Washington Jr.

|

| Durham NC Morning Herald 18 May 1954 |

The students from D.C. did not win their case, but the struggle was not finished. In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear collectively five separate cases filed by the NAACP regarding school segregation. Though each case was different in some aspects, they all involved children from Black elementary schools that were deemed inferior to white schools. Instead of challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. Arguments were presented to the court over three days in December 1953. The five consolidated cases were given the title: Brown v. Board of Education.

Five months and eight days later on 17 May 1954 Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the court's unanimous opinion. School segregation by law was unconstitutional and "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place." This landmark decision overturned three Supreme Court rulings from over a half-century earlier that sanctioned segregation in both public and private schools.

The three lead attorneys who presented this monumental case were George E.C. Hayes (1894–1968), James Nabrit, Jr. (1900–1997), and Thurgood Marshall (1908–1993), a NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice. Among the several legal scholars and attorneys assisting them to prepare this case was a professor from Howard university School of Law, James Aaron Washington Jr.

|

| Winston-Salem NC Journal 18 May 1954 |

In this 1954 map of the 20 states that required schools to be segregated, it is worth noting that only 11 were states that seceded from the Union in 1861. Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri were called Border States and stayed in the Union. Kansas became the 34th state on January 29, 1861 when it was admitted as a free state. West Virginia, originally the northwestern part of Virginia, rejected Virginia's secession and its people organized their own government and constitution, eventually joining the United States as the 35th state on June 20, 1863. Wyoming, Oklahoma, and New Mexico were still territories during the Civil War and were not admitted as states until 1890, 1907, and 1912 respectively.

In February 1953 as the nation began to take notice of the school segregation cases being considered by the Supreme Court, James A. Washington Jr was a member of a panel of legal experts that discussed it at a meeting of an inter-racial group celebrating Abraham Lincoln's birthday. Mr. Washington said, "We're living in a time when the Supreme Court can't go backwards, but must go forward. We can be sure we're not going to lose anything by its ruling. The old idea of separate-but-equal facilities was so imbedded even in us, that we took two months to write an argument that did not mention it."

That was the insidious way that racism had become an accepted part of American culture and its laws. Even oppressed people can become accustomed to injustice, bigotry, and abuse. The attorneys in this historic case knew the only way to reverse racial segregation was to insist that all people were equal under the Constitution.

The 1954 ruling on Brown v. Board of Education unleashed countless legal challenges and years of public protest, often horribly violent. The civil rights movement was beginning to slowly bring about changes but it would be decades before all schools were desegregated. Even today, almost 70 years later, America continues to struggle with issues of equality and fairness in our public education systems.

What surprised me when I tried to solve the puzzle of the unidentified African-American face in my two photos of the East Palestine Glee Club and Orchestra, was that James Aaron Washington Sr. was not just a peculiar accident of tolerance and acceptance. Someone recognized that he had merit and potential. However it happened, James was given a chance to thrive in an environment of Ohio people who accepted him without following the engrained prejudices of North Carolina.

What is more amazing is that his legacy became his son and namesake, James Aaron Washington Jr., who turned these pictures into a kind of prophesy of what life could be like if people were judged by their character instead of the color of their skin.

I will never know the entire picture of these two lives, James Washington, father and son. Did James Senior share his stories of East Palestine High School with his children? Were they happy ones, full of promise and hope? And did James Junior take these stories to heart when he used his education and knowledge of the Constitution to correct one of America's great injustices?

To begin this story I chose a line from Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous speech delivered on 28 August 1963 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Hundreds of thousands of people were there that day. I hope James Aaron Washington, father and son, were with their families somewhere in that great congregation listening to Dr. King's inspiring words.

CODA:

There are still a few pieces missing from this puzzle.

|

| Washington D.C. Evening Star 22 July 1977 |

Dr. James A. Washington of Columbia Rd. died on Thursday 21 July 1977. He was 86 years old. He was survived by his wife Vivian A. Washington; one son, Judge James A. Washington Jr.; one daughter, Placide T. Robert; eleven grandchildren; and sixteen great-grandchildren.

The mystery is his honorific, Dr. James A. Washington. What did that mean? Was he a doctor of medicine? A doctor of divinity? A doctor of some academic study? Until I found his obituary, I had not uncovered any evidence of higher education other than two years at Shaw University. But when I looked closely at the 1940 census I saw that on the question, "highest grade of school completed", Vivian Washington listed C2, two years of college and James had C5 for five years. Yet for most of his life James worked for the U.S. Post Office. How was he a doctor?

Most physicians would put the letters M.D. after their name. A church pastor would have Rev. Dr., and an academic would have PhD after their name. My hunch is that James was a pharmacist and that he operated the Service Drug Store in Asheville from around 1926 until he left in 1928. It was taken over in December 1928 by the Y.M.I. Drugstore which was in the adjacent shop space. One of his mentors in Asheville was the Y.M.I. director and bandleader, Dr. William Johnson Trent Sr. (1873–1963) who ran the Y.M.I. drug store and later became president of Livingston College in Salisbury, NC. By odd coincidence, his son and namesake, William Johnson Trent Jr. (1910–1993) went on to be a civil rights activist and the first executive director of the United Negro College Fund, from its inception in 1944 until 1964.

|

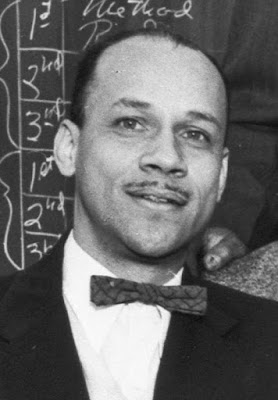

| Judge James Aaron Washington Jr. Source: The O’Shaughnessy’s Reader |

|

| Raleigh NC News and Observer 2 September 1998 |

James Aaron Washington Jr continued representing clients in other civil rights litigation in the 1950s while remaining professor at the Howard University School of Law. For a time he was assistant, and later, dean of the law school. After a long distinguished career he was appointed judge to the Superior Court of the District of Columbia in 1971 by President Richard Nixon. Despite a serious injury from an accidental fall in 1976 that left him confined to a wheelchair, he remained on the bench until his retirement in 1984. He died at his home in Silver Spring, Maryland, outside of D.C., on 29 August 1998. He was 83.

For the first and second parts of this series check out:

Postscript

A few months after I wrote this series I came across two more photo postcards from East Palestine High School. Both were listed by the same dealer in Ohio and had been attached to an old scrapbook found at a family estate sale. Other that the caption on the front there are no annotations for date or names. The E. P. H. S. Glee Club is clearly the same group of boys that are in the photo that started this series, but here they are playing their instruments. The instrument that James Washington is blowing is a bugle, not a trombone as I first thought. The fellas are showing off a bit more in this photo with some goofiness that lets their individual personalities come out. I bet they made an impressive good noise too.

The second photo is identified in the caption as the E. P. H. S. Track Team 08. There are twelve boys wearing white athletic shirts and shorts and their coach. The boys have sashes across their chests with initials EPHS. The tallest boy in the back is the drum major in a top hat in the Glee Club photos. James Washington is standing back row left and skipping one over is another African-American boy that I believe is likely William Mitchell, James' cousin, who was mentioned in the April 1908 report that Mrs. Louise Sims was taking her son James and his cousin William to Canada for a summer vacation, courtesy of her new employer.

I was unable to find William Mitchell in census records or newspaper reports in Asheville, North Carolina or East Palestine, Ohio. But I did find a North Carolina certificate of death of a William E. Mitchell, dated 23 January 1922, who died from "tuberculosis pulmonary acute pneumonia". His age is listed as 29 years, 4 months, and 10 days with a date of birth of 22 September 1892, so he was a year and almost five months younger than James Washington which fits with the age of the boy on the track team, about 16. In 1922 William Mitchell is described as a "negro" and married, though his wife is "unknown". Information on his parents is also "unknown." He was employed as a "Chauffeur & Mechanic" but his employer is "unknown", too. He lived in Franklinton, NC, but for the previous 18 months he resided at the U. S. Veteran's Hospital in Oteen, North Carolina, about five miles east of Asheville. Next to his name was a rank "D. C. S. Pending. Pvt. Canadian Forestry Service." I don't know the meaning of "D. C. S. Pending." The medical officer noted that his disease was caused by "military service."

Is this the same person? I'm not sure, but, despite his tragic death, it does seem possible that it is. It's very intriguing that this William Mitchell worked in Canada. Perhaps after that summer holiday in 1908 with James, William stayed there, since he did not appear in the 1910 census for either East Palestine or Asheville. Surely his presence in East Palestine must have provided James Washington with a close friend who could share memories of Asheville and the liberating experience of being free of segregation in East Palestine.

These two photos offer new evidence and even more questions. I knew James played on the track and field team in high school as his name was included in a 1907 newspaper report, though Mitchell's was not. But look closely at this photo and we see that every young man stands proudly wearing their school sash just as we would expect to see them in 2024. But this is 1908. How was this remarkable photo of unprejudiced equality even possible then? The stories of James A. Washington, Sr., and now William Mitchell, are not yet finished.

Postscript

# 2

# 2

It amazes me that yet again I am able to add more photos to James A. Washington's story. Here he appears in another postcard of the East Palestine High School track team. This time he sits on the floor in front of his fellow teammates with a small medal pined to his shirt. Several of the boys were also pictured in the glee club photos.

The ten boys strike a more serious pose, perhaps feeling a bit self-conscious at being photographed in their short pants and sleeveless shirts. The postcard was mailed from East Palestine on 19 May 1909 to Mrs. C. E. Oliver of Pittsburg, PA at Mercy Hospital. There is a story hidden in this message too.

Will be up Saturday

if my heal (sic. heel, head?) gets

well. I will have to

jump against the

same fellows that I

jumped against Saturday.

if my heal (sic. heel, head?) gets

well. I will have to

jump against the

same fellows that I

jumped against Saturday.

Here is one more photo of another East Palestine High School athletic team that James was not part of, but other members of the glee club were. It's the E.P.H.S. basketball team of the 1908-09 school year.

The photographer has helpfully added surnames to the photo just below the basketball.

08 — 09

Wolfe Forney Dorsey

Ward Atchison

Oliver Arnold Atkinson

E. P. H. S. Basket Ball Team.

Wolfe Forney Dorsey

Ward Atchison

Oliver Arnold Atkinson

E. P. H. S. Basket Ball Team.

The boy seated left is named Oliver and is surely the boy who sent his mother the previous postcard where I believe he is in the back row second from left. He also appears in the other track team photo seated left just in front of James. I think he is also the snare drummer in the glee club photos.

I think both photos illustrate a level of comradery and friendship that made East Palestine High School a remarkable place for James and his cousin William to get an education. Perhaps one day I will be able to find answers to my many questions.

I think both photos illustrate a level of comradery and friendship that made East Palestine High School a remarkable place for James and his cousin William to get an education. Perhaps one day I will be able to find answers to my many questions.

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where everyone else is taking a walk this weekend.

5 comments:

Excellent sleuthing!

I meant to ask, you said that James Washington Jr attended all white schools in DC. Was that an error?

Thanks, Kristen. James Jr attended segregated schools in D.C. but my sentence was awkwardly worded. I'll fix it.

What a wonderful tribute to these men (and their families) who made such a difference in the lives of many others in this world. I so enjoyed reading about their lives, and you presented details in an academic fashion (should have been expected of course!) that reads as well as any biographies I've enjoyed. The use of each of the documents visually is much more readable than a bibliography! This is the history that must not be lost! These men were leaders through their efforts...and I wonder how much they realized at the time how significance their positions would become. I think these three chapters are publishable.

I "can't believe" how much you managed to find out and dare not even attempt to guess how much time you must have spent on research + writing. Deserves to be a book, really... (agreeing with Barbara)

Post a Comment