Look at that!

It's unbelievable!

It's fantastic!

It's unbelievable!

It's fantastic!

How is that possible?

What keeps it up?

It's so..so...so BIG!

What keeps it up?

It's so..so...so BIG!

What's the commotion about?

Why all the fuss and clamor?

Why all the fuss and clamor?

Zeppelin kommt!

Zeppelin kommt!

Zeppelin kommt!

The reason for everyone's agitation was that they wanted to see the Luftschiff, the flying airship, the Zeppelin. It was 1909 and people everywhere were excited to get a glimpse of this new German machine that could defy the law of gravity and fly. For the first time the very idea of a human being moving across the sky amidst the birds and the clouds was no longer unimaginable.

The German postcard artist Carl Robert Arthur Thiele (1860 – 1936), gives us an artist's impression of the madcap pandemonium created when the first Zeppelin appeared high above a German city. Thiele, who signed his artwork Arth. Thiele – Lpzg (for Leipzig, his hometown), was featured in my story from September 2020, Auf Urlaub — On Leave with another set of his postcards from 1916-17.

This postcard was sent on the 15 October 1909 to Marie Schmeer of München, Bayern (Bavaria). The publisher was Verlag F Eyfriedt of Düsseldorf.

* * *

The object in the sky that fascinated the public was the Luftschiff III built by the German company, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, founded by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, known as the Graf von Zeppelin, (1838–1917). It was built in Friedrichshafen, a city on Lake Constance (the Bodensee) in Southern Germany near the borders of Austria and Switzerland. In 1862 Ferdinand von Zeppelin was a young officer in the army of Württemberg, when he was assigned as a military observer to the United States' Union Army. During the Peninsular Campaign he watched the use of observation balloons and later took a flight in one. This inspired him in the 1890s to create a larger lighter-than-air craft with a rigid frame that would be powered by engines and be steerable to any direction.

Using his own fortune, with support from the King of Württemberg as well as donations from subscribers, Zeppelin succeeded in building his first air ship, the LZ 1. It made its first flight over Lake Constance on 2 July 1900. It carried a crew of five men and flew a distance of 6.0 km (3.7 mi) in 17 minutes, reaching an altitude of 410 m (1,350 ft). After two more flights in October 1900 when the LZ 1 established a new speed record that beat the French electric-powered non-rigid airship, La France, Count Zeppelin ran out of money and was forced to dismantle his prototype airship.

In January 1906 Count Zeppelin completed construction of his second airship, the LZ 2. Unfortunately it was badly damaged by high winds on its maiden flight on 17 January 1906 and subsequently had to be scrapped.

Despite this setback, the LZ 2 proved that Zeppelin's new engineer, Ludwig Dürr (1878 – 1956) had fixed many problems in the original design, so a new sister airship, the LZ 3 was built. Its first flight was made on 9 October 1906. As originally built, the LZ 3 was 126.19 m (414 ft) long with a diameter of 11.75 m (38 ft 6 in). Within its aluminum frame were gas bags that displaced a volume of hydrogen gas equal to 11,429 m3 (403,600 cu ft). Power to its propellers was provided by two Daimler piston engines of 84 hp each. It's maximum speed was 40 km/h (25 mph).

This photo postcard of the Zeppelin Luftschiff III was sent from Nürnberg, Bavaria to Miss Mahtilde(?) Semmer in London on the 29-??-1909.

* * *

The image at the top of my post is taken from this second postcard of Arthur Thiele's "Zeppelin Kommt!" series. It shows a colorful group of Germans who have rushed out from their shops onto the street for a glimpse of the great Zeppelin airship. There are about ten different occupations depicted including a chimney sweep, a butcher, a hair dresser, and carpenter's mate. Because it is a painting the colors give a better representation of people than a photograph could do at the time. In the 1900s camera technology was not able to capture movement very well, so artists still had an advantage.

The postcard was sent from Berlin on 19 August 1909 to Paul Bernhagen, also of Berlin. The writer used all four sides of the card with a florid cursive style, and their signature is along the top edge. I believe it is a woman, Johanna Steinca(?). No doubt Paul knew who she was.

* * *

The third postcard in this series shows another street scene, this time at night. Numerous people in their bedclothes and slippers have gone to their windows to see a Zeppelin which is illuminated by a search light from the airship's gondola.

This postcard was mailed on 3 November 1909.

* * *

This next postcard has a bird's eye impression of a Luftschiff high above a dramatic landscape with a heroic vignette of Graf von Zeppelin in the corner. The artist is unknown.

The first flight of the LZ 3 in 1906 carried eleven people and was in the

air over Lake Constance for only 2 hours 17 minutes. A second shorter

flight was made the next day, but after that success Count von Zeppelin

had the airship deflated and stored for the winter. Nonetheless it was successful enough to convince the German government to take a serious interest in this new aeronautical

machine. It offered Count Zeppelin a grant of 500,000 marks if his new airship could

make a flight lasting 24 hours.

However Zeppelin's designers knew that the LZ 3 was not capable of making that

goal, so he assigned his engineers to make a better airship, the

LZ 4. This airship made its first test flight on 20 June 1908, but it only lasted 18 minutes because of a problem in its steering mechanism. After repairs, further trials were taken on 23 and 29 June, and then on 1 July 1908, the LZ 4 made a spectacular 12 hour cross-country flight over Lake Constance to Zürich, Switzerland and back again. A distance of 386 km (240 mi) during which time the airship reached an altitude of 795 m (2,600 ft).

On its return the LZ 4 was prepared for the 24-hour endurance trial, which would be a return flight to Mainz. On 13 July 1908 the airship was re-inflated the with fresh hydrogen to ensure

maximum lift, but when it tried to take off the next morning engine problems forced a delay. Finally on the morning of 4 August 1908 thousands of people came out to see the LZ 4 lift off for its grand test flight. It carried 12 people onboard and had enough fuel for 31 hours of flight. The route would take it over Konstanz, Schaffhausen, Basel and Strasbourg on the way to Mainz.

Throughout the flight the LZ 4 was plagued by engine and fuel problems. At times it struggled against the wind while in an extreme nose-down or nose-up position. It rose to a height of 884 m (2,900 ft) which forced the release of its precious reserves of hydrogen gas. These difficulties forced an emergency landing on the Rhine near Oppenheim, 23 kilometres (14 mi) short of Mainz, where five crewmen and all unnecessary material was unloaded.

The LZ 4 finally reached Mainz about 11:00 PM and immediately set off on its return to its hanger on Lake Constance. But bad luck had a tight grip on the airship. Early the next morning another engine failure forced it to land for repairs at Echterdingen. That afternoon a gust of wind tore it from its moorings. Soldiers and groundcrew struggled to hold onto its tether ropes. A member of the crew who had remained on the airship managed to turn it back towards ground, but in the process the airship struck some trees which punctured gas bags and ignited a disastrous fire. Within minutes the huge Zeppelin was a twisted wreckage.

|

| Zeppelin LZ 4 Source: Wikipedia |

An estimated 40 to 50 thousand spectators witnessed this terrible catastrophe on 5 August 1908. Yet newspaper reports on Count Zeppelin's misfortune led to a spontaneous wave of support for his airships. Within 24 hours his company had received enough unsolicited donations from the German public to build another airship. Ultimately the total donations realized over 6 million marks which provided Zeppelin with a secure financial basis to continue with his aeronautical experiments.

My postcard with the cloud view of Zeppelin's majestic airship was produced to commemorate this disaster, and may have been sold to raise funds for a new airship. The back of the card has a clear postmark and handwritten date of 21/8/08, which was just two weeks after the LZ 4 accident.

* * *

On this next postcard of Arthur Thiele's Zeppelin series, a large crowd has gathered in a street to cheer an airship floating in the sky. It may reflect the kind of reception that the LZ 4 received in August 1908 before the accident. This card was sent from Stuttgart on 12 September 1912.

* * *

Here is another artist's rendition of a Zeppelin Luftschiff in the air from a vantage point that would have been impossible for any camera. The artist is unnamed but the caption reads:

Graf Zeppelin lenkbares Luftschiff über dem Rheintal

~

Count Zeppelin steerable airship over the Rhine valley

~

Count Zeppelin steerable airship over the Rhine valley

After the destruction of the LZ 4, the Zeppelin company went back to the LZ 3 and made modifications to improve it. By late October 1908 it was ready for test flights. On 27 October it flew for 5 hours 55 minutes with the Kaiser's brother, Admiral Prince Heinrich, on board. On 7 November 1908, Crown Prince William was a passenger, and it flew 80 km (50 mi) to Donaueschingen, where the Kaiser was staying. Despite poor weather conditions the flight was a great success and two days later LZ 3 was officially accepted by the German government. The next month Graf von Zeppelin was awarded the Order of the Black Eagle by Kaiser Wilhelm II.

This postcard has a postmark from Heerlen in the Netherlands dated 25 January 1909.

* * *

The Zeppelin LZ3 made numerous flights in 1909 and was likely the inspiration of Thiele's postcard series. This image shows another nighttime flight with people clambering onto roofs to get a good look. Firemen, oddly with real fire torches, try to restore order.

Piloting an early airship seems difficult enough that trying to fly after dark must have been particularly risky. The searchlights were used as an aid to landing and avoiding trees and buildings.. Very little was then known about the nature of the Earth's atmosphere at high altitudes. The Zeppelin's giant sausage shape made a perfect sail to be pushed around by winds and the early petrol engines were very underpowered. The airship was equipped with rudders to control horizonal movement left and right, and ailerons to change vertical elevation.

But the biggest challenge to steering an airship was understanding how the mass of the entire Zeppelin was offset by the lighter-than-air hydrogen gas. Vast quantities of water were stowed as ballast to adjust trim and altitude, which affected performance whenever the airship changed position. Flying a Zeppelin required a new 3-dimensional thinking that had to learned through trial and error. The consequence of a mistake was death.

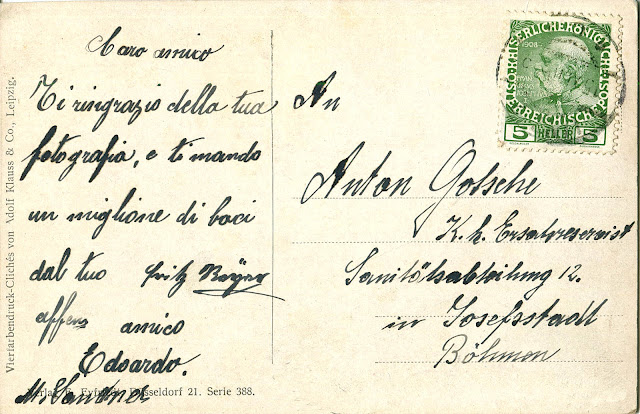

The postmark on this card is affixed to a postage stamp of the Austrian Kaiser Franz Josef. It is too faint to read but the stamp has a helpful printed year of 1908. My guess is 1909-1910.

* * *

This next postcard from my collection is another unknown German artist's painting of a Zeppelin over a city. But there is a second object above the skyline, an airplane with four wings. The perspective makes it appear almost half the size of the Zeppelin, when in fact it was smaller than the boat on the river.

While Count Zeppelin was working on his dream of a lighter-than-air craft, two brothers from Dayton, Ohio were pursuing their idea for a heavier-than-air machine. Their first powered flight on the beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina was on 17 December 1903. By May 1906 they secured a U. S. patent and by 1908 their Wright flyer was on its way to France. On August 8th, just three days after the LZ 4 disaster, Wilbur Wright gave the first demonstration of powered flight at the Le Mans racetrack witnessed by hundreds of thousands of people.

Just a month later on 17 September 1908, Orville Wright was seriously injured and his passenger, Lt. Thomas Selfridge, was killed in a crash while demonstrating the Wright airplane at Fort Meyer, Virginia. Lt. Selfridge became America's first victim of an airplane accident. Yet despite this tragedy, Orville and Wilbur were able to sell contracts to the governments of the United States, France, and Germany. On 13 May 1909, the Flugmaschine Wright Gesellschaft, the Wright Flying Machine Company was formed in Berlin.

At the end of August, Orville and his sister Katherine Wright were in Berlin to give a demonstration of their airplane. On 29 August, on the orders of the Kaiser, Count Zeppelin flew there, with his latest airship. Over 100,000 people came to see it land. The following week Orville flew exhibitions of his airplane to similar sized crowds.

On September 15, Orville and Katherine traveled to Frankfort to accept Count Zeppelin's offer of a ride in his new airship. They flew 50 miles to Mannheim. Days later, Orville set a new airplane record for a flight that lasted 54 minutes 34 seconds and reached an altitude of 565 feet.

The postmark on this postcard is from Frankfurt am Main and dated 25 September 1909. A printed caption reads Internationale Luftschiffahrts Aussellung Franfurt a M. ~ International Aviation Exhibition, which I presume meant it was a special souvenir of the exhibition. (The riverboat in the picture looks odd because its engine smoke funnel is hinged to allow it to pass beneath bridges.)

* * *

The final postcard in Arthur Thiele's Zeppelin set shows a wedding party interrupted by the sight of a Zeppelin outside the church. The bride does her best to restrain the enthusiasm of her husband-to-be. There was no cake at the reception. This card was posted on 25 July 1910.

* * *

|

| 1960, Echo 1 satellite Source: Wikipedia |

In the summer of 1960 my mom and I were living at my grandparent's home outside Washington D. C. One day, when I was not yet six, my grandfather took me outside at dusk to see something unusual. He pointed to a shiny dot of light moving across the sky and told me it was called Echo. My vision was probably a bit blurry then, so I didn't see much and wasn't very impressed. But the name stuck, and later I learned that the shiny dot was the communication satellite, Project Echo.

It was the first satellite project by the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Echo 1 was a spherical balloon 100 feet (30 m) in diameter with a non-rigid skin made of 0.5-mil-thick Mylar. It had a total mass of 180 kilograms. The construction of the balloon was not too dissimilar to Count Zeppelin's airships. The silvery globe functioned as a passive reflector, not a transceiver. Radio signals sent from a ground station were reflected by its metal surface and bounced back to Earth. For my grandfather, born in 1905, it must have seemed amazing that modern engineering could achieve such a thing. Count Zeppelin would have been impressed too.

By an odd coincidence, (and there are a lot in this story), two days ago, on 18 February 2021, NASA successfully landed the Perseverance rover robot vehicle on the surface of Mars. Because there are no cameras nearby to record the actual event, a NASA artist illustrated the moment of touchdown. The rover was lowered by the "skycrane" part of the lander assembly. It was launched from Earth on 30 July 2020 with the mission spacecraft hurtling through space at 24,600 mph (about 39,600 kph). The trip to Mars took nearly seven months and traveled about 300 million miles (480 million kilometers).

|

| Landing of Mars rover, Perseverance 18 February 2021 Source: NASA |

In 1909 Count Zeppelin's airship

was a wonder in every sense of the word.

was a wonder in every sense of the word.

When people turned their eyes upward to the sky

and saw this enormous cylinder

slowly progressing across the clouds,

they were amazed by a new unfamiliar concept.

Mankind can fly.

and saw this enormous cylinder

slowly progressing across the clouds,

they were amazed by a new unfamiliar concept.

Mankind can fly.

Today in 2021,

we take Orville and Wilbur's airplanes,

if not Ferdinand von Zeppelin's airships,

for granted, as a familiar common science.

But as the new illustrations and photographs

of the Mars mission are released,

they should fill us with that same wonder.

It's a feeling of profound astonishment

that sends a person running outside

to look up at the sky.

we take Orville and Wilbur's airplanes,

if not Ferdinand von Zeppelin's airships,

for granted, as a familiar common science.

But as the new illustrations and photographs

of the Mars mission are released,

they should fill us with that same wonder.

It's a feeling of profound astonishment

that sends a person running outside

to look up at the sky.

Look at that!

It's unbelievable!

It's fantastic!

It's unbelievable!

It's fantastic!

Mankind can touch

the surface of the Red Planet.

10 comments:

I love old postcards and these are awesome. The Zepplin was quite the marvel even though it was a failure in so many ways.

An amazingly interesting and detailed post. It must have taken hours of research. Having said that I have to say that Thiele's postcards stole the show for me. So much amusing detail. I spent ages looking at them. Thanks for sharing them.

Great collection on an unusual theme!

I liked these Theile postcard paintings best among those you've shared. What a great imagination! Of course your theme of flight with Zepplins and Wrights was also excellently done. I am glad you got to see an early satelite as well. Did you know there's a site that lets me know every time the space station is going to fly over Black Mountain? Let me see if I can find that link, because I'm sure people can use it wherever they live...https://spotthestation.nasa.gov/sightings/index.cfm. Another opportunity to go outside and look up at the heavens with men in them.

Our technology advances so quickly that I doubt many experience the sense of wonder and excitement exhibited in the postcards. The next big thing gets replaced tomorrow.

I grew up in the San Francisco East Bay community of El Cerrito and every once in a while we'd see (and hear - the sound was unique) blimps come flying overhead. I guess it was a little exciting. We'd certainly run out to see them. I haven't seen one in years, though. They don't normally come flying over the woods and mountains. I never thought to wonder about it though - why are they called blimps? Guess I should look it up. :) Love all your postcards, by the way. So colorful and full of comic action!

Theile's postcards are delightful. I enjoy the humor and movement in them. You did a great job of finding an interesting "Z" and putting together so many links, past and present.

Lots of wonderful pictures and a great write-up!

Another amazing post. Who knew the letter Z could trigger such a sweeping history of air travel? The postcards capture the public fascination with aviation -- so much so that they were willing to leave their daily/evening pass times, and even a wedding, to view the awe-inspiring Zeppelins. You are so right that artists were/are able to capture events where cameras are inadequate/absent. And I learned something new about the U.S. Civil War. Had not previously heard about the observation balloons.

I agree with Molly. What a rich post. I love the commotion they caused and how the colorful postcards captured it.

Post a Comment