Look up!

Where?

The sky! Look up at the sky!

Do you see it?

It's so bright! It's so big!

What is it?

Where?

The sky! Look up at the sky!

Do you see it?

It's so bright! It's so big!

What is it?

It's the COMET of course!

IT'S FINALLY HERE!

IT'S FINALLY HERE!

People who read newspapers

had been anticipating its arrival for months,

while astronomers had awaited its return for decades.

Yet this large unfamiliar light in the night sky

still took many regular folk by surprise.

had been anticipating its arrival for months,

while astronomers had awaited its return for decades.

Yet this large unfamiliar light in the night sky

still took many regular folk by surprise.

However a few elders

remembered seeing it once before.

It was no stranger to earth.

In fact it was a regular visitor

that had paid a call here

many, many, many times before.

remembered seeing it once before.

It was no stranger to earth.

In fact it was a regular visitor

that had paid a call here

many, many, many times before.

It was called Comet Halley.

|

|

Halley's comet in 1066 depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry Source: Wikimedia |

It took its name from the great English astronomer,

Edmond Halley

(1656 – 1742), who determined in 1696 that a comet he

saw in 1682 was the same one recorded in 1607 and 1531 and that it orbited

the Sun on a periodic cycle of about 75–76 years. Halley calculated that it would return in 1758, which it did, though he did not live to see it. Further study ascertained

that the comet's high elliptical orbit is affected by the gravitational pull of the

giant planets Jupiter and Saturn giving it a period that varies between 74

and 79 years which is a relatively short cycle for a comet.

Over centuries of regular human observation Halley's comet acquired a

reputation as an omen of great portent. Its first confirmed sighting was recorded by Chinese

chroniclers in 240 BC. It also returned in 12 BC leading some people to

believe it had a connection to the biblical story of the Star of Bethlehem.

However there are better explanations for that phenomenon, such as planetary

conjunctions or other comets that appeared closer to the date of Jesus'

birth.

Halley's comet probably made its most fateful appearance in 1066 when it aligned with the Norman Conquest of England. Later that same year, King Harold II of England died at the Battle of

Hastings which let William the Conqueror claim the throne. The comet is

depicted on the famous Bayeux Tapestry and described as a star four times

the size of Venus, shining almost as bright as the moon.

In 1910 Halley's comet was scheduled to return to the skies of earth, and

the German postcard artist, Arthur Thiele (1860-1936), had a good idea of how the public

would react. The year before, Thiele painted a postcard series about the

excitement generated in 1909 by the Graf Zeppelin's giant airships, which I

featured in my story,

Zeppelin Kommt!. Once again he cleverly anticipated that this comet would create another opportunity to

illustrate the public's mania for crazy events.

[ Click any image to see it at full screen ]

We begin with pandemonium at a typical German outdoor restaurant. A sign

reads

Hier speist man wie bei Muttern. Heute abend grosses Knödel essen. -

Here you dine like at mother's. Tonight eat big dumplings. Dozens of diners scurry to get a look at a

light in the sky. One amorous couple ignore the comet to indulge in

some canoodling.

This card was posted on 17 April 1910 to

Fräulein Amy Kapf (?) in Bamberg. With this return, Halley's comet was

expected to become visible to the naked eye around 10 April and reach

perihelion, the orbital point nearest the sun, on 20 April.

Since the last visit by the comet was in 1835, the 1910 appearance was the

first occasion that scientists could use photography to record its image.

Thiele's postcard caricature was remarkable close to what was seen weeks

later by astronomers at the Harvard College Southern Observatory in

Arequipa, Peru. This photo was made with an 8-inch Bache Doublet,

Voigtlander camera. The exposure time was 30 minutes.

|

|

Halley's comet taken 21 April 1910 at the Harvard College Southern Observatory, Arequipa, Peru Source: Wikimedia |

Previously in 1835 the only way to record Halley's comet was to paint a

picture. The Swiss-English landscape artist, John James Chalon (1778 – 1854)

made this watercolor of his impressions seeing the comet. The small group of

adults and children gathered by a small telescope seem charmed by the novelty of the comet.

|

|

Watercolour painting depicting observation of Halley's comet in 1835 Source: Wikimedia |

In this second postcard, Thiele shows a crowd of people

in front of a building trying to get the best view. In the foreground a wurst vendor is distracted

by the comet as a dachshund make off with her fare. A sign on a window

reads: Auskunft / Eile mit Weile – Information /

Haste makes waste.

This postcard is dated 4 May 1910 and was sent via the

Austro-Hungarian postal service. I think, the writer's language is

Czech.

Astronomers had made great advances since the days of Edmond Halley. Besides

photography, modern scientific technology in 1910 included ways to collect

spectroscopic data from the comet's light. It was expected that the comet's

approach to the sun would create a spectacular effect, and that on 19 May

1910, the earth would pass through the tail of the comet.

Unfortunately the

first spectroscopic analysis of the comet's tail showed that it contained

the toxic gas cyanogen. This led the French astronomer and popular science

author, Camille Flammarion (1842 – 1925) to claim that the gas from the

comet's tail "would impregnate [the Earth’s] atmosphere and possibly snuff

out all life on the planet". When Flammarion's concern was reported, many

people around the world panicked and bought gas masks and "anti-comet

umbrellas" for protection. Scammers profited on sales of quack "anti-comet

pills".

|

|

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 18 May 1910 |

Other learned "experts" thought the comet's tail might shower the earth with diamonds or other gemstones. Some astronomers theorized that the comet could produce extreme tidal effects. People in Duluth, Minnesota worried about high water or freak waves on Lake Superior damaging shoreline communities. People became concerned that the comet might spark electrical effects in the atmosphere. Telegraph and wireless companies reportedly took measures to protect their equipment. Farmers in Wisconsin removed the lightning rods on their barns and houses.

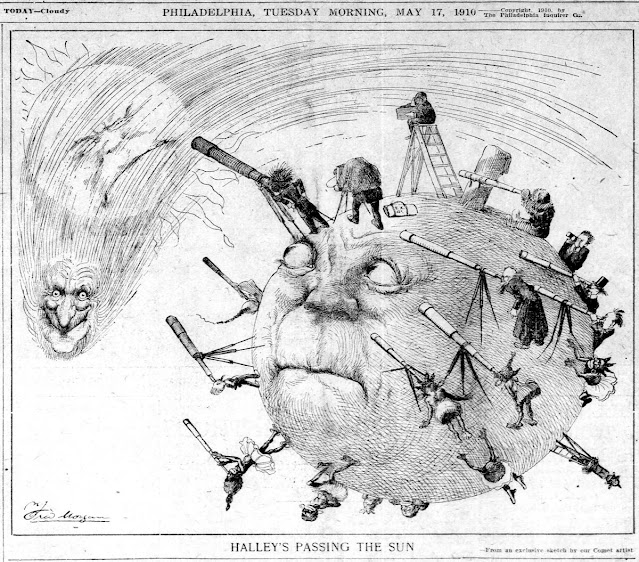

Scientists tried to reassure the public and many newspapers printed lengthy

descriptions of what to expect from the comet. But in May 1910 it's likely

that the information most people remembered came from cartoons

like this one entitled "More Spring Cleaning" showing Mr. Earth running away from the comet's broom sweep. It was published on the front page of the Philadelphia

Inquirer.

This postcard was sent on 14 May 1910 to Frau Berta Voigt of Bernberg,

Germany. I don't think the writer makes any reference to

der Komet.

The year 1910 was only 75 years after 1835, so there were a good many

seniors around who remembered witnessing Halley's comet when they were

children. One 90 year old man, a druggist in Pittsburgh, said, "Of course I

remember the visit of Halley's comet, 75 years ago. I don't forget things so

easily as all that. " He noted that many people were scared and that the comet had a terrifying apperarance.

An old woman in Kalamazoo, Michigan, age 85, said, "Seventy-five years ago

people, the same as today, were talking and prophesying that the world would

end when Halley's comet met the Sun." She continued, "I was only 10 years

old and I lived in New York state at the time, but I remember seeing the

comet in the early evening."

"It was in the northwest, instead of the

northeast, as now, and was very distinct, brilliant, and beautiful. It had a

very long tail which I could see clearly and distinctly. People fully

expected that the comet would destroy the earth just as they do today, but

here I am just as much alive today as then."

_ _ _

In this next postcard Thiele depicts another moment of pandemonium, this time

outside a billiard hall. A cluster of men have paused their game to

rubberneck from a window, disturbing the patrons at an outdoor cafe table.

This postcard was posted from the port city of Kiel, Germany and dates from

19 May 1910, the day that the earth would pass through the comet's tail. But

like the previous card, I don't think the writer mentions anything of

der Komet.

For astronomers, physicists, and other cosmologists this passage of the earth through the comet's tail was an exciting natural event but certainly nothing to be alarmed about. Many recognized it as an important scientific opportunity and had prepared new devices to measure and record any celestial effects. But the scientific method is based on asking questions, and in 1910 scientists were not entirely sure about what kind of answers they might learn. As newspapers reported on the possibilities of new discoveries, the general public could not help finding some of these ideas alarming.

|

| The Great January Comet of 1910, the Daylight comet, photographed by the Lowell Observatory Source: Wikipedia |

The people of the world had some cause for concern as they had already been startled by a comet earlier in the year. On 12 January 1910, diamond miners in the Transvaal, South Africa spotted an unusually bright light in the pre-dawn sky. This became known as the Great January Comet of 1910, officially designated C/1910 A1. Because it shined brighter than Venus, it was often called the Daylight Comet as its head and tail were particularly visible during daytime. In fact the Daylight Comet, in comparison with Halley 's comet, was considered the brighter and more impressive heavenly body.

In Arthur Thiele's fifth postcard in his series, the frenzied comet watchers have provoked runaway horses and dogs outside of a Bäckerei von Sauerteig –

Bakery of sourdough.

This card has a postmark of 27-5-1910 from Aachen, Germany

Newspapers in America competed with each other by publishing extensive commentary, predictions, and cartoons about this momentous wonder. Yet despite the papers' best efforts to be clear about the comet's benign aspect, many people had reason to think it was a harbinger of bad news.

At the end of April, the great American humorist and writer, Samuel Clemens aka Mark Twain, died. His birthday was 30 November 1835, two months after the comet was first sighted in 1835, and he died on 21 April 1910, just a day after the comet reached its closest point to the sun. In Clemens autobiography, published in 1909, he said:

I came in with Halley's comet in 1835. It is coming again

next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest

disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's comet. The

Almighty has said, no doubt: 'Now here are these two unaccountable

freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.'

|

|

San Francisco Examiner 18 May 1910 |

The other bad omen in 1910 occurred on May 6th when King Edward VII suffered a heart attack and died. Though he had endured a period of ill health, some people thought the comet precipitated his death. His funeral was arranged for March 20th and nearly every royal monarch and person of rank in Europe attended the ceremonies in London.

{Note that the swastika badge pictured in the cartoon of Mr. Earth is an ancient symbol of good luck. In 1910 it had none of the connotations it would have 20 years later.}

The last postcard of Thiele's shows another throng of people gathered around a telescope set up outside a grand hotel. An open top automobile has stopped at the hotel entrance. Its chauffeur and passengers wrapped up in menacing headgear, typical of the outfits worn by riders of early automobiles to avoid road dust and exhaust smoke, look for the comet. One woman has fallen through the hotel's glass awning. Another woman and her dog have ducked for cover beneath the car, while a suspicious-looking man runs past holding several sacks, perhaps cash stolen from the hotel.

This postcard was sent from Frankfurt, and though the stamp is missing with half the postmark, the writer has helpfully given a date of 11 February 1912. The belated use of Thiele's postcard is likely due to the popularity of the artist who produced hundreds, if not thousands, of similar witty cards over his long career. I think the card's topic of comet hysteria probably remained a source of collective humor, at least up until the summer of 1914.

On May 19th, the day after the earth had passed through the comet's tail, newspaper headlines complained of its failure to produce any display of pyrotechnics. They seemed disappointed in the comet's lame performance and dissatisfied that the world had not come to a sad end. "Comet's Tail Plays Trick, Fails to Sweep the Earth" reads one headline.

Another paper was inspired to write a jingle, partly wagging a finger

at the fearmongers.

at the fearmongers.

Comet Is Come

Comet Is Gone

Old World

Still Wags

Merrily

Along.

Comet Is Gone

Old World

Still Wags

Merrily

Along.

Celestial Vagrant on Its Way Back Into Space Leaves Earth Dwellers Little the Wiser, No Better and No Worse.

_ _ _

Other papers denounced the astronomers who were somehow at fault for its behavior.

A cartoon from the May 20th edition of Chicago's Inter Ocean summed up the public's general mood of annoyance at Halley's comet. The caption reads: "The Runaway Comet. Astronomers, all over the world, are astounded at the failure of Halley's comet to follow the course calculated for it.—News Item." A bespectacled man wearing a wizard's pointed hat rides the earth. He shouts, "Whoa! Whoa there!" as he tries to lasso a swift horse labeled Halley's Comet. A little girl as Luna, the moon, weeps. Mother/Father Earth says, "Never touched me!"

|

|

Halley's comet, 29 May 1910 Source: Wikimedia |

Arthur Thiele's witty postcard illustrations captured a period of social history better than any series of photographs. The tremendous advances made in science, engineering, and technology during first decade of the 20th century seemed to offer the world limitless riches. Thiele was responding to a new perspective that had not really been imagined before. The great airships of Graf Zeppelin, the soaring airplanes of the Wright Brothers, and now Halley's comet, were turning the eyes of mankind towards the sky. The world was no longer defined by just two dimensions. The earth's atmosphere now opened a third direction that promised human flight, and maybe even space flight would no longer be a fanciful notion.

The French author, Jules Verne (1828 – 1905), who could have been one of those children gazing up at Halley's comet in 1835, certainly knew the power of imagination.

“In

spite of the opinions of certain narrow-minded people, who would shut

up the human race upon this globe, as within some magic circle which it

must never outstep, we shall one day travel to the moon, the planets,

and the stars, with the same facility, rapidity, and certainty as we now

make the voyage from Liverpool to New York!”

– Jules Verne, From the Earth to the Moon, 1865

– Jules Verne, From the Earth to the Moon, 1865

4 comments:

Thiele's postcard art seems somehow appropriate for the holiday season -- the warm colors, the steaming dumplings, the sausage vendor who has also dropped her knitting in astonishment. Thiele appears to have reveled in the humorous aspects of reactions to Halley's Comet -- and he certainly capitalized on it from many angles. You are so right: photos are great, but the paintings really capture the mood. Have a great holiday season!

I just discovered this post, and will spend some time reading it more fully tomorrow. It looks quite interesting!

Oh yes, leave it to Thiele to paint all kinds of situations about Halley's Comet! Pretty fun to look at, and thanks for the translations!

Interesting postcards, and impressive background research!

Post a Comment