Jagdabenteur

~

Hunting Adventure

~

Hunting Adventure

A manned balloon careens through the air. Its anchor line has snared a man, dragging him through a marsh. A hunting party of stout gentlemen are suddenly alarmed that their hapless servant still holds onto baskets of their victuals and wine as he is carried away. It is clearly not the hunting adventure they had planned. Their gun dogs swim out to retrieve the sausages.

This humorous postcard was produced by Arthur Thiele (1860-1936),

a prolific German artist that I have featured several times on my blog. In 1909

he created a series of cards illustrating the public excitement for Graf Zeppelin's giant airships which I

wrote about in Zeppelin Kommt!. In early 1910 he followed up with a similar postcard series on Halley's Comet which I featured in December 2021 in Der Komet Kommt!. And earlier this year I showed off a series he did on the early automobiles, Das Auto.

This postcard of a holiday mishap is part of a series Thiele did about another modern vehicle, the balloon. Like his other postcards, Thiele turns his eye to the way new things sometimes create new problems. It's a timeless observation that is no less clever a century later. This postcard's back has a stamp of the Deutsches Reich with a postmark of 18 October 1910 from Pforzheim, a city known for its watch-making and jewelry manufacturers, and located in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany.

Thiele had a genius for picking out the latest fads and then painting humorous cartoons that poked fun at people's wacky modern enthusiasms. And 1910 was an opportune year to do that as it was a time when every day seemed to bring reports on exciting new innovations. In 2022 the idea of someone flying in a balloon seems a quaint lighthearted recreation as today's advanced aviation technology can fly people around the world in super fast jets or even space ships. But in 1910 the idea of human flight was a very novel concept that was just beginning to catch the attention of the public. The giant airships of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, whose steerable airship designs first flew successfully in 1900, were now at a development stage as his company tried to figure out how to make air travel practical, safe, and economical for the public. It was not until late 1908 that the Wright brothers demonstrated their fantastic airplane to the general public, and though by 1910 Orville and Wilbur had many more competitors in the air, all of the pioneer inventors of heavier-than-air flying machines were still struggling to overcome thousands of technical obstacles.

On the other hand, balloons were actually the oldest proven aircraft. The first balloon flight was made in 1783 by the brothers Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier who amazed people in Annonay, France with their giant hot air balloon. But all the early aeronauts found it very difficult to make repeated flights and very easy to fail, often with tragic results. It was not until the late 19th century that science and engineering introduced better materials and machines that finally allowed aviation to really take off. By 1910 all three flying concepts—balloons, airships, and aeroplanes—were competing to master the laws of gravity and Arthur Thiele recognized that each machine had its comic potential.

To explain this mania for aircraft during the first decade of the 20th century, I used a marvelous invention of the 21st—the internet search engine. In the vast Newspapers.com archives, my favorite digital newspaper collection, the word "airship" shows up only 4,347 times in 1899, and then jumps to 6,417 for the year 1900 when Zeppelin's first airship took flight. By 1910 the number of occurrences increased to 110,678. In contrast the word "aeroplane", the original common spelling of "airplane", appeared in newspapers only 617 times in 1900, but rose to a height of 180,747 times in 1910. Since "balloon" can be a verb used in financial reports or a noun describing a child's circus treat, I searched instead for "balloonist". In 1900 it was used only 2,299 times in newspaper reports, but in 1910 the number climbed to 10,199.

So Arthur Thiele was not drawing on just his imagination to chose ballooning as a subject of mockery. It was a pretty popular topic in 1910 and it was not difficult to find examples of balloonists in the news. For instance in February 1910 a Mr. John Dunville crossed the Irish sea in a balloon traveling eastward from Ireland to England. While passing over Wales he encountered a heavy snowstorm and a temperature of 27° before reaching an altitude of 10,000 feet. The trip took him 4 hours and 45 minutes to cover 164 miles.

|

| Manchester. England Courier 13 February 1910 |

* * *

Das gestörte Picknik

~

The disturbed picnic

~

The disturbed picnic

Hovering over a lake a pair of boorish aeronauts try to increase their balloon's buoyancy by releasing sandbags from their gondola. The rain of gravel and cinders upsets a group of young picnickers who did not expect this kind of precipitation.

Driving a balloon is limited to following the direction of contrary winds and only rising or falling according to the subtle relationship of lift and ballast. Today most ballooning is done using hot air balloons, but the powerful burners and propane tanks used to heat the air did not exist in 1910. Instead most balloonists in this era used gas-filled envelope to provide lift, either with hydrogen or coal gas. One problem with hot air balloons is that they require a larger air bag in comparison to gas balloons which can be much smaller for the same lifting power. Also the air heaters used in the early hot air balloons used very heavy fuels like wood or charcoal which restricted the time aloft. Gas balloons were lighter and more feasible as they could stay up longer. However the gas, particularly hydrogen, was extremely flammable and forced aeronauts to be very conscientious about prohibiting anyone smoking on the balloon.

This postcard was sent from Konstanz, a university town situated at the western end of Lake Constance in southern Germany, the same lake where Graf Zeppelin tested his first airships. The postmark and message date is 15 January 1911.

The very nature of humans flight is, of course, inherently risky in the extreme. The newspapers regularly reported on aviation accidents like this one from Long Beach, California in March 1910. A young balloonist named Eugene Savage (or sometimes Henry Savage by more distant newspapers) was attempting to reach a record height and had filled his balloon to its capacity. As he ascended from a location near the amusement park along the Long Beach oceanfront the balloon suddenly burst at about 300 feet.

Fortunately the balloonist was equipped with a parachute but as the balloon's envelope lost gas it entangled Savage and the parachute. Only in the last seconds did the chute open enough to slow his fall. He struck his head on a street curb and was momentarily unconscious but somehow escaped any serious injury. The crowd of people who had come to watch were so horrified that most turned away unable to watch the man's certain death. Other reports noted that this was not the young aeronaut's first accident as he had previously crash landed several times into the ocean, luckily escaping serious injury. Those saltwater dunkings likely contributed to the deterioration of the balloon's fabric envelope.

* * *

Ein fatale Situation

~

A fatal situation

~

A fatal situation

A balloon has crashed into a tree leaving the gondola dangling from the branches as the limp balloon collapses over some telephone wires. Three passengers including a woman hold onto the balloon rigging as local folk look up at them in helpless concern, especially at the lady struggling to keep her skirt on.

Because balloons lack steering, there were frequent collisions with trees, buildings, and other structures that endangered the balloonists. In 1910 parachutes were a relatively new ballooning accessory but were very unsophisticated, and sometimes terribly ineffective too. Much of this risk stemmed from a general ignorance of weather and the atmosphere. Even meteorologists of the time were unsure of wind and temperature conditions at high altitude or even of oxygen levels at the extreme heights that balloonist were attempting to reach.

This postcard was sent on 9 July 1910 from Ilsenburg, Germany, a small town at the foot of the Harz mountains between Hanover and Leipzig.

Once a balloon achieves its chosen cruising height the balloonists experience no sensation of wind as a balloon effectively moves only as fast as the air speed. To predict the weather at high altitude requires very different knowledge than what sailors learn from watching wind and clouds at sea level. Many balloonists lost their lives to storms like the four men in April 1910 who perished after their balloon was struck by lightning in a sudden thunderstorm near Berlin. When found it was evident from the bodies that the men had fallen from a great height. This report is not nearly as gruesome as others which often went into great detail about balloon disasters. The final paragraph recounts that the popularity of "flight fever" in Germany, where many towns now had balloon clubs, would undoubtedly lead to aviation accidents becoming as frequent as automobile accidents. Of course Arthur Thiele has another postcard series devoted to funny auto mishaps. I'll post that story when I acquire the complete set.

Cameras in 1910 were not very good at recording outdoor images against the bright background of the sky, so photos of balloons are not very clear or detailed. The early motion picture cameras had the same problem so it was not until the 1920s when photography was advanced enough to capture motion that balloons in flight appear on film. Here is a short newsreel of a 1926 balloon race, incorrectly labeled as Hot-air ballooners take off for cross-country race . It gives us an idea how exciting and challenging it was to see gas balloons soar off into the sky.

* * *

Des Bauern Himmelfahrt

~

The farmer's ascension

~

The farmer's ascension

A farmer's wife rushes out to the yard shouting for help as her poor husband is carried away in his privy by a balloon's anchor line. The geese and pigs find it all very amusing.

This postcard was sent from München, Bayern or Munich, Bavaria on 30 September 1910. All of Arthur Thiele's cards were published by the Adolf Klauss & Co. of Leipzig, Germany and distributed to news agents and shops throughout Germany, Austria, and judging from postmarks probably Switzerland, Netherlands, and Belgium too.

Many early balloonists seemed intent on achieving a record altitude. This required careful planning and carrying precise barometric equipment. Obviously by 1910 no human had ever climbed much higher than the European Alps or American Rockies. Scientists were still uncertain what might happen to the human body beyond 20,000 feet. They expected a drop in temperature but could not predict how low it might go for a balloonist. In 1908 the Graf Zeppelin's airship, the LZ4, reached an altitude of 2,600 feet (795M) but it was later destroyed in a windstorm while moored on the ground. For fixed wing aircraft 1910 was a record breaking year for altitude. It began in January with a new record of 4,164 feet and was followed by four more fliers each breaking the previous record until in December, Archibald Hoxsey flew a Wright Model B to an earth shattering 11,474 feet (3,497m).

But this was nothing compared to what balloonists could do. The best record so far had been set in July 1901 by two German meteorologists, Arthur Berson and Reinhard Süring who piloted a hydrogen balloon to an astounding altitude of 35,433 feet. Their balloon, the Preußen, had an open basket and steel cylinders filled with oxygen. Their flight led to the discovery of the stratosphere.

In May 1910 two American aeronauts, A. Holland Forbes and James Carrington Yates took their balloon up to 20,600 feet setting a North American record, but the attempt nearly cost them their lives. They were descending when an accident with the balloon's rip cord released the gas at about 300 feet. They were saved by a rubber air mattress stored on the bottom of the balloon's basket.

|

| Charlotte NC Evening Chronicle 12 May 1910 |

* * *

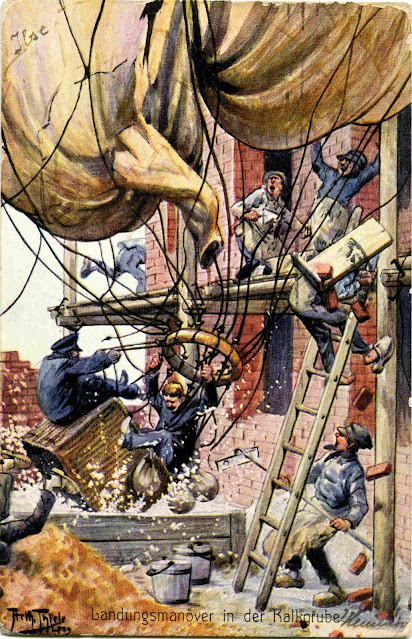

Landungsmanöver in der Kalkgrube

~

Landing maneuvers in the lime pit

~

Landing maneuvers in the lime pit

Two aeronauts crash their balloon into a building worksite making an undignified landing into a pit of cement. The masons and workers flee for their lives.

This postcard was sent from Hamburg, Germany on 20 July 1910. The writer has one of the boldest penmanship styles I've ever seen, that would do credit to any doctor or attorney.

In October 1910 a Philadelphia physician and amateur balloonist, Dr. Thos. E, Eldridge, went up in a balloon at the Interstate Fair in Trenton, New Jersey and reached 2,000 feet when he realized something was wrong with his balloon. Fortunately his purpose had been to demonstrate a parachute, but on this occasion the emergency was real and his chute opened properly to the enthusiastic cheers of the people at the fairground.

|

| Philadelphia Inquirer 1 October 1910 |

* * *

Die abgerissene Kirchturmspitze

~

The broken church spire

~

The broken church spire

A balloon has collided with a church spire, capturing its weather vane with the balloon's basket. A brave town watchman keeps a precarious hold of the vane while other town folk rush to help him before the balloon can escape into the sky. A fearless Dachshund throws his weight into the struggle.

This is my favorite of Arthur Thiele's six balloon theme postcards. I like the higher perspective and the frenetic movement conveyed by the balloon and the people below it. I suspect steeple collisions were probably a common accident with balloons. The postmark on the card is from Chemnitz, Germany and dated 27 April 1910. Chemnitz is the third-largest city in the German state of Saxony after Leipzig and Dresden.

The competitive instinct of earlier aviators to fly higher, longer, and

farther motivated many patrons to sponsor air races, and ballooning had

its share of wealthy enthusiasts. One of the first races for gas balloons was the Gordon Bennett Cup

sponsored by James Gordon Bennett Jr.,

the millionaire sportsman and owner of the New York Herald newspaper. It

opened in Paris in 1906 with a simple goal for contestants that they

"fly the furthest distance from the launch site." In October 1910 its

fifth annual event was held in St. Louis, Missouri. Entrants came from

all over the world shipping their balloons and equipment to the center

of the North American continent. St. Louis was already famous for its

worlds fair exhibitions and had hosted this race in 1907. That event was

won by a German team that traveled 1403.55 miles in 40 hours.

This year the stacks were high as an American team hoped to win a back-to-back first prize, having taken the cup in 1909 when the contest was held in Zürich, Switzerland.

The

balloon America II was manned by Alan Ramsay Hawley and Augustus Post

who somehow caught a faster wind than their competitors by reaching an

altitude of over 20,000 feet. Since there was no way to communicate with

the balloonists, race officials counted on ground observers to locate

each balloonist team but this

was very unreliable. After all the other balloons had come down, the

American

aeronauts were still unaccounted for. Another day passed and race officials considered organizing search parties but still there

were

no sightings. Newspapers around

the country anxiously awaited word on the fate of the America II. Since

the wind direction was expected to take the balloons

toward the Great Lakes, it was feared that the American balloon might

have perished after landing in water. Finally after ten days Hawley and Post were

discovered by hunters in a remote region of Canada. They were okay but exhausted from several days effort to walk out of the wilderness.

They recorded a flight time of 44

hours and 25 minutes from St. Louis until a storm forced them to land on a hillside 58

miles (93 km) north of Chicoutimi, Quebec. Initial reports claimed they had

traveled 1,350 miles from

St. Louis to Quebec, but it was later revised to 1,173 miles, nonetheless a record distance for a balloon in that era.

Every since I was a young boy I've been fascinated by lighter-than-air flight and have read many books on the early pioneers of aviation. I sometimes imagine that if I had not taken up music I might have tried a career in ballooning or maybe even dirigibles or blimps. This is partly to explain my interest in Arthur Thiele's mischievous illustrations of balloons. aeroplanes, and airships. But it was also because Thiele was observing an utterly new experience for mankind—the wonder of human flight.

What was it like to see a balloon floating past the clouds for the very first time or watch a Zeppelin gracefully turn around in the sky? It's a level of astonishment that has few comparable examples in our time a century later. Thiele certainly knew what that amazement of human flight felt like, but as an artist he also took note of how common folk had the good sense to object to the new problems caused by new things. Only a talented artist with his gifts could combine those grand ideas into a picture and make you laugh at the same time.

This week I also discovered a different kind of ballooning that in another life I definitely would have taken up. It's called Balloon Jumping and it was popular around 1927. When I was growing up I dreamed up this exact same notion of a person harnessed to a small gas balloon with just enough buoyancy to lift about 3/4 of a person's mass. I imagined it would give me the power to leap over tall buildings like Superman. Until this week when I found this newsreel footage of it on YouTube, I did not know that it was once a real extreme sport.

Maybe it will make a comeback! But I have to admit it looks a little bit risky to me now.

To finish with an ironic coda, I include this 1910 report on ballooning from the great state of Kansas, famous for its vast prairies, thunderstorms, tornadoes, and witches and wizards. The report in the Topeka newspaper extols the fun of ballooning, "safe as other sports." with "little danger in making ascensions." But as Dorothy, Toto, and the Wizard of Oz could attest, the real risk with ballooning was in the descent.

|

| Topeka KS Daily Capital 18 September 1910 |

This is my contribution to Sepia Saturday

where you can always find a good bargain.

where you can always find a good bargain.

3 comments:

Whow...just fantastic art and comedy of Theil's post cards! I enjoyed your comments and the extensive history also...you are well versed in the early efforts of air travel, but I'm glad you didn't (yet) take on the sport of jumping tall buildings with your personal balloon.

Great collection of balloon/cartoon cards, and related true stories! Funny coincidence, I just recently (this/last week) watched a documentary on Swedish television (in two parts) about Zeppelins and the Hindenburg disaster.

The postcards are great! A fun & interesting post. Too bad about those who didn't survive the experience of ballooning. There are some beautiful balloon rides over Lake Tahoe where I go on vacation. I'd love to take a balloon ride, but I'm not brave enough. I have to take a Valium even to fly on planes. Oh well.

Post a Comment